Drag, buoyancy, water-repellence -- they all affect how an athlete moves through water, but money too influences what the world's top swimmers choose to wear in competition.

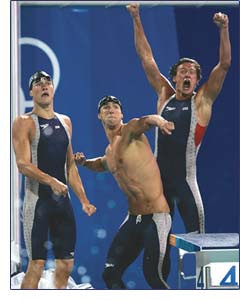

USA's 2004 Summer Olympic swimmers outfitted in Speedo suits

USA's 2004 Summer Olympic swimmers outfitted in Speedo suits

Then, less than two months removed from the close of Olympic swimming competition, Americans resumed their assault on the record books. Between October 2004 and this past September, U.S. swimmers set four long-course and four short-course world records. In addition, eight long-course and four short-course American records fell during the same period. "This is supposed to be an off year after the Olympics," said USA Swimming president Ron Van Pool, during his State of USA Swimming address Sept. 17. "What do you think of an off year?"

Ask anyone. These are heady times for international swimming.

But the race to be the best hasn't been limited to the Amanda Beards and Ian Thorpes of the world. The past 10 years have witnessed an unprecedented push among rival swimwear manufacturers to introduce technological innovations to suits in the form of fabric composition, texture and cut they claim lend a competitive edge to the wearer.

The biggest visible splash -- and controversy -- came during the 2000 Summer Games in Sydney, were bodysuits re-emerged after a decades-long hiatus. "Two-thousand was the year that everything changed," says Jonty Skinner, director of performance science and technology for USA Swimming. "At the 2000 Olympic Games, all of a sudden everyone looked like they were racing in pajamas."

Make no mistake. These weren't the same bodysuits donned by athletes diving into the frigid Bay of Zea at the 1896 Athens Games. Nor were they the type of extended tank top worn by U.S. freestyler-turned-Tarzan Johnny Weissmuller while winning five gold medals during the 1920s. These new-generation suits employ compressive materials designed to streamline the body -- in some models, from neck to ankle.

Still, determining just how much a swimsuit aids the swimmer, if at all, remains a slippery exercise. It might be more accurate -- not to mention in the spirit of international swimming rules -- to discuss today's suits in terms of how they inhibit the swimmer to a lesser degree than their product predecessors or even, some would suggest, bare skin. Others argue bare skin is preferable on the arms and lower legs, where pulling and propelling might actually suffer from slipstream suit technology. Susie O'Neill set a world record in the 200-meter butterfly at the 2000 Australian Olympic Trials wearing a tank-topped, knee-length one-piece. Then, wearing an ankle-length bodysuit in Sydney, O'Neill was beaten in the event for the first time in six years.

If you're waiting for actual swimming competition to sort out the swimwear hierarchy, don't hold your breath. While longtime swimwear giant Speedo boasts that more than half of last year's Olympic gold medalists wore Speedo suits, Nike, a relative newcomer to the natatorium set, saw a greater percentage of its comparatively limited stable of sponsored athletes bring home gold. This is where technological innovation purporting to influence drag, buoyancy and water-repellence meets brute marketing strength. And it's often left to the athletes to wade through the scientific research -- at least as much scientific research as is packaged in slick product brochures -- when selecting a suit, if they even have a choice.

"In a lot of cases, it's not up to the swimmer," says Matt Zimmer, team and promotions director for swimsuit manufacturer TYR Sport. "We sponsor hundreds of clubs and dozens of colleges around the country, but we're not really talking to the kids. We're talking to the administrators, the coaches, the team moms -- whoever is making that decision on what suits they're going to buy. A lot of times the kids end up with whatever the coach has decided, not necessarily what they would have chosen given the option, because they never saw the options."

To say that today's swimwear market is saturated with options would be an understatement. Consider that several manufacturers -- Speedo, TYR, Arena, The Finals and Diana among them -- are dedicated exclusively to aquatics. Other companies, such as shoe-and-apparel rivals Nike and adidas, have also taken the plunge in the interest of product diversification and media exposure. (Rumor has it Nike couldn't wait for televised track and field coverage to kick in during the climactic days of Olympic competitions, and thus decided to attach its trademark Swoosh to swimwear, where it would be seen earlier in the schedule.)

Regardless of the suit maker or its motives, each is likely to offer a range of available technologies -- from textured fabrics to water-repellent fabric coatings. An array of styles and cuts are also common, including stroke- and gender-specific suits. In addition to traditional racer-back one-piece suits for women and briefs for men. there are "jammers" (with waist-to-knee coverage), "long johns" (waist to ankle), "short johns" (the aforementioned knee-length, tank-topped bodysuit) and full bodysuits (covering the swimmer from the neck to the wrist and ankle).

The two manufacturers that have taken competitive swimwear innovation to the greatest technological extreme, at least in this country, are Speedo and TYR. The companies, both based in California, have independently designed suits to reduce drag on the swimmer, and they couldn't have approached the task in more different ways.

Using computational fluid dynamics software to identify areas of drag on a swimmer's body, Speedo sought foremost to reduce skin friction drag (caused by water flowing along the swimmer), which along with pressure drag (water moving around the shape of the swimmer) and wave drag (water being displaced by the swimmer in the form of a wake) comprise the three main contributors to overall drag. TYR, meanwhile, opted to attack pressure drag (the greatest contributor to overall drag) and wave drag by studying swimmers in the world's only annular flume (a donut-shaped pool with a traveling computer lab bridging the water), located at the Center for Research and Education in Special Environments at the University at Buffalo.

Speedo focused its research on starts and turns, during which the swimmer is totally immersed, reasoning that if a suit can reduce drag in those phases of a race, it should also be somewhat effective during the actual stroke phase, when the swimmer's body is partly out of the water. Because TYR sought mostly to reduce wave drag (and claims its suits do so by as much as 53 percent), the stroke phase was a critical focus of the company's research all along.

The end products even look different. While Speedo has structured its suits so that everything -- from panel seams to tiny ribs within the fabric -- run parallel to the path of the swimmer, TYR has purposefully added ridges -- or tripwires -- perpendicular to the swimmer's path.

Here's where hydrodynamic theory hits the water.

In the years prior to the 2000 Sydney Games, Speedo developed what it called the FastSkin® suit. Presented as competitive swimwear's state of the art, the suit actually took its cues from something prehistoric -- the skin of sharks. Specifically, the suit's fabric featured the aforementioned ribbing pattern, which when viewed in cross-section resembles a zigzag of peaks and valleys. When water flows parallel to the carefully sized and positioned ribs at precisely the right speed, it only comes in contact with their peaks, thus reducing friction. (adidas marketed a similar suit but has since scaled back its presence in the aquatics market, save for its endorsement deal with the Australian icon Thorpe.)

The Finals, a manufacturer that primarily serves high school and club programs, has begun targeting elite swimmers with suits utilizing its two-year-old X-Cellerator technology -- the incorporation of wider "channel stripes" into compressive fabrics as a means of reducing friction drag. According to Jeremy Tongish, The Finals' director of merchandising, tests using a spinning, underwater cylinder covered with different suit fabrics show that X-Cellerator fabrics reduce drag by as much as 20 percent compared to a standard nylon-Lycra® blend.

"There are pretty significant differences between fabrics," says Barry Bixler, an aerospace engineer who serves as head of testing and analysis for Speedo. "The smoother the fabric the better -- with one exception. If you take the surface and raise and lower it into peaks and valleys, research has shown that you can reduce friction drag even further."

Speedo's FSII, which debuted at the 2004 Olympics, incorporates a second, more pliable fabric panel along the swimmer's sides for comfort and flexibility, as well as dozens of small bumps concentrated on the upper chest and upper back to trip laminar flow into turbulent flow (more on this later). TYR's Aqua Shift⢠suit also made its first waves (albeit reduced ones, the company would argue) in Athens. The suit incorporates a mere half-dozen longitudinal bands located across the chest, upper back and buttocks. No thicker than a shoelace, these so-called tripwires are incorporated into the suit fabric to convert laminar flow (water hugs the surface of the body in motion) into turbulent flow (water is stirred into tiny whirlpools) at the curvy points on the body where laminar flow would otherwise separate from the body. The idea is that turbulent flow hugs the body better than separated laminar flow, thus reducing wake and wave drag.

"So the question is, if you increase the friction drag but you decrease the pressure and wave drag, who wins? And what we found out is that you can reduce the overall drag by tripping the flow, increasing the friction drag and thereby reducing the pressure drag," says Joe Mollendorf, University at Buffalo professor of mechanical and aerospace engineering, who co-authored the research conducted on behalf of TYR and published in the June 2004 issue of Medicine & Science in Sports & Exercise, the official journal of the American College of Sports Medicine. "Swim meets are won in hundredths of a second, so -- technique and everything else being the same -- a small reduction in the overall drag will give the swimmer a slight advantage."

Meanwhile, Arena, a company in the midst of a North American resurgence decades removed from its affiliation with legendary U.S. Olympian Mark Spitz, has concentrated almost solely on the drag-reducing properties of fabrics and form-enhancing fit. Its PowerSkin® fabrics are woven as opposed to knitted, a distinction the company says results in a smooth, lightweight, water-repellent (due to chemical treatment), ultra-thin and ultimately fast suit. This fall, the company began North American distribution of PowerSkin Xtreme®, the suit worn by nearly a quarter of all medalists in Athens. It adds to the original PowerSkin fabric a microscopic riblet texture designed to further reduce friction (not unlike the Speedo technology), as well as more forgiving side and knee panels for improved comfort and flexibility in demanding events such as the breaststroke.

The first time U.S. Masters swimmer Jacki Hirsty wore a PowerSkin bodysuit, in December 2000, she not only swam a personal-best time of 28.06 seconds in the 50-meter freestyle, she set a Masters world record in the 45-to-49 age group that still stands today. "I dove in and felt like I got shot out of a cannon. I thought that I had false started, because I couldn't see the rest of the field," says Hirsty, who was so impressed with the suit that she subsequently joined Arena as a representative. "I've held the Masters world record in the 50-freestyle in almost every age group, but the time I set in the PowerSkin was remarkable."

Remarkable, certainly, but whether such advantages are desirable depends on who you talk to within swimming circles. Purists were quick to point out the potential for unfair competition between those with high-tech suits and those without.

Moreover, no independent, comprehensive Consumer Reports-type study has been conducted that compares all brands of suits head-to-head. Critics of FINA, international swimming's governing body, say the organization's own attention to the issues at hand has been insufficient, if not laughable. FINA efforts have ranged from crude buoyancy tests, in which empty suits were submerged in water to see if they float, to mere modesty checks in an era of increasingly thin fabrics. "They consider the suit as part of the costume," Skinner says of FINA officials. "They almost liken it to apparel.

They didn't see it as a technical issue, and they didn't go about testing the suits to see whether they might be doing things that would take away from the sport." FINA rules state that "no swimmer shall be permitted to use or wear any device that may aid his speed, buoyancy or endurance during a competition." Enforcement, however, has been virtually nonexistent.

In 2003, researchers at Arizona State University presented to the American Swimming Coaches Association a USA Swimming-sponsored study on buoyancy characteristics of suits manufactured by adidas, Arena, Nike, Speedo and TYR. "Our main goal was to show these suits are either within FINA rules or against the rules," says Bryan Morrison, one of the study's authors and the current head swimming and diving coach at Valparaiso University. Without naming brand names, pending the study's publication in a peer-reviewed journal, Morrison adds, "Most of the suits came back as applying a buoyant force on the body, which goes against the rules. Yet they are still allowed in competition."

The reason, argues anyone willing to talk about it -- and that's just about everyone -- is money: FINA can't fathom upsetting the status quo of well-paid stars and world-record times. "This was the greatest swimming event ever at an Olympic Games," gushed FINA executive director Cornel Marculescu, in Athens last August. "Great athletes, great stars, and at the end of the day eight world records. We had the highest TV audience number worldwide and positive feedback from all the rights holders. There were excellent audiences and full venues."

Brent Rushall, a professor emeritus of exercise and nutritional sciences at San Diego State University and usually an outspoken critic on issues relating to competitive swimming, has long decried the sport's increasingly compromised integrity - even going so far as to offer FINA his own unsolicited rule-change proposals. At the height of the initial technology debate, in April 2000, Rushall wrote in a letter to The Court of Arbitration for Sport in Lausanne, Switzerland: "The basic question remains, should swimming races be contests between persons or the best-equipped persons? If one opts for the latter, then no longer can anyone claim to be the world's best swimmer. It will have to be the world's best swimmer wearing "Brand X" performance-enhancing swimsuit. The implication of this is that a world champion might not be the world's best swimmer."

Several countries wrestled independently with this very dilemma in the run-up to the Sydney Games, for purely practical reasons. The United States and Great Britain were among those that considered banning certain suits from their respective Olympic trials so that talent could be fairly judged -- that is, until manufacturers began providing free suits to all participants.

Skinner, for one, still has reservations, even if everyone is outfitted in the same suit. "To me, the reason that the bodysuit works against the sport of swimming is that it's not an equal playing field device," he says. "Let's say we did a buoyancy test on two different people who were at the same level of ability. Without a bodysuit on, Test Person No. 1's hips rise to the surface of the water. Test Person No. 2's hips ride at a 45-degree angle. After putting a bodysuit on, Test Person No. 1's body rides at the surface of the water -- no gain, no advantage to putting the bodysuit on. As for Test Person No. 2, his body now rides at a 15-degree angle to the surface of the water. He's gained a distinct advantage by putting a bodysuit on. So when those athletes race with bodysuits on, Test Person No. 2 has more potential to improve his performance and time than Test Person No. 1. That is not an equal playing field. Ultimately, you want the person with the most talent who trained the hardest to win the race. That's the purist point of view."

Skinner, however, tempers his stance as it relates to the recent shredding of records. "To some degree, I think suit technology has contributed to that," he says, adding that an acceptance by coaches of swimmer preparation outside the pool, including land-based training, nutrition and psychology, has played an even greater role in drawing competitive swimming out of the doldrums of the mid-1990s. "The world is doing a better job now of training and preparing athletes for competition. There is a greater number of swimmers globally who have taken advantage of training technology, environments and options and propelled swimming forward dramatically."

Even manufacturers recognize that suit technology can only take a swimmer so far. "We like to think that if you put [four-time Olympic gold medalist] Janet Evans in a gunnysack that she would still have broken world records," says TYR's Zimmer. "We don't want to take anything away from the athletes, but we certainly don't want to inhibit them in any way."

Auburn University's recent dominance of the NCAA swimming and diving championships may serve as evidence that the suits don't necessarily make the men and women. The Tigers have won three straight men's titles -- two in suits manufactured by TYR, the latest in Speedo. AU women posted three consecutive championships under contract with TYR, before settling for second place with Speedo this past season.

Competition for such marketplace bragging rights is fierce, and despite price tags on some suits approaching $400, manufacturers insist their profit margins are greatly eroded by necessary investment in research and development, materials, and patent protection. "We can come up with a wonderful new team print and sell it to high schools and summer leagues for a couple of years and make a heck of a lot more money than we're going to make with Aqua Shift," says Zimmer. "By and large, these suits are aimed at 1 percent of the total competitive swimming population. The economies of scale work against everybody. How do we justify it? If we didn't have a product like this, we wouldn't have any professional athletes, we wouldn't have any colleges, the door wouldn't be open. At least now it's a level playing field as far as technology is concerned, and may the best man win."

And so, the competitive push continues unabated. Well, not completely. Zimmer is still scratching his head over FINA's decision to ban a TYR product called Aqua Band, a sleeve covering the swimmer from elbow to wrist, prior to the 2004 Olympics. "If you think about it, it's not really all that innovative," Zimmer says. "It's essentially a full bodysuit; we just took out the material from the elbow to the shoulder. They allow long sleeves, so why would this be any different?"

No amount of costly legal wrangling would ultimately provide TYR with a satisfactory answer. FINA offered only a rewording of its rules to include language that identified arm and leg bands as illegal, without offering any proof that they enhance performance. It's not even clear whether the promise of enhanced performance is what the world's top swimmers value most. In the end, money may prove to be an even more influential factor in suit selection than drag, buoyancy and water-repellence. "A majority of the athletes on the national team are professionals, and they pick a suit not because of any recommendation that we might make on our end, but because they are aligned to a certain brand of suit by contract," says Skinner. (A handful of elite swimmers, including eight-time Olympic medalist Michael Phelps, wear suits custom tailored to their body shape, while the majority of his U.S. teammates simply wear suits off the rack.)

And because swimwear technology is advancing at a steady clip, Skinner advises Olympic-caliber swimmers to demand a clause in their contract that allows them to wear a rival brand if it is proven superior. "You've got to have that option," he says, having witnessed at least one swimmer risk victory in Athens by wearing what Skinner considered an inferior suit. "Come 2008, one or all of those brands are going to come out with the latest and the greatest. And the way marketing goes these days and all the hype that surrounds it, it's really hard to tell if their claims are real."

Next year, Speedo will launch a water-repellent, fast-drying fabric called XD Skinâ¢, which is designed to feel lighter in the water. But that development alone provides few clues as to what Beijing might bring two years later. Bixler offers only that Speedo, by design, is on a product-rollout-per-Olympiad pace.

To be sure, the competition won't be far behind. "Sports innovation is a requirement," Zimmer says. "It does get harder and harder, but you know you have to do it. It's part of your daily process as a company -- to try to find ways to do things better. At the end of the day, once swimmers put that suit on, they have to feel like it's going to take them to the next level."