In some circles, outrage accompanied the 2001 opening of Miller Park, the Milwaukee Brewers' new home. The state senator who cast the deciding vote in favor of a sales-tax increase to pay the public's $290 million portion of the construction cost had been recalled in a public referendum, and three workers had died after a crane collapsed, delaying the stadium's scheduled opening by a year. The stadium's fan-shaped retractable roof proved problematic, necessitating a $13 million fix paid for by a settlement reached between the Miller Park Stadium District and Mitsubishi Heavy Industries of America, averting further litigation. That one signature element was a prime culprit in the stadium's ultimate $400 million construction cost, at the time the second-highest price tag for a new professional baseball stadium.

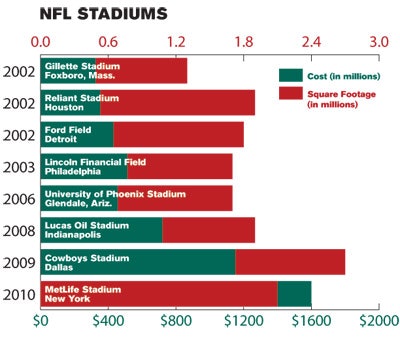

Over in the National Football League, little outrage accompanied the opening of Detroit's Ford Field or Houston's Reliant Stadium in 2002. The two buildings featured a fixed roof and a retractable fabric roof, respectively, and both were very much in line, cost-wise, with other state-of-the-art buildings of the time. Ford Field, designed to incorporate a neighboring warehouse, came in at $430 million, while Reliant's much-simplified retractable roof design kept the building's cost at $352 million, putting the two venues third and fourth at the time on the list of professional football stadium construction cost.

(AP Photo/James D. Smith)

(AP Photo/James D. Smith)

Ten years later, and it's nowhere near adequate to say that the ante has been upped. A handful of team owners have raised and re-raised, and now the size of the pot is such that there's no space on the table to deal the cards. The three newest pro football stadiums have cost $720 million (Lucas Oil Stadium, 2008), $1.15 billion (Cowboys Stadium, 2009) and $1.6 billion (MetLife Stadium, 2010). Major League Baseball hasn't seen quite that level of inflation, but it has produced the three most expensive ballparks in history in 2008 (Nationals Park, $611 million) and 2009 (Citi Field, $900 million; Yankee Stadium, $1.5 billion). Perhaps it's worth noting that MLB's newest venue, four-month-old Marlins Park - the league's sixth to feature a retractable roof, and its smallest in total seating capacity - cost a mere $515 million. On the other hand, the stadium's complicated financing plan (currently being investigated by the Securities and Exchange Commission), will lead to a final public cost to repay debt incurred by the stadium's construction of $2.4 billion over the next 40 years.

Okay: For the purposes of comparison, debt service probably has no place in this discussion. (Only God and Jerry Jones know what the ultimate cost of Cowboys Stadium will be, and neither is talking.) Not that making comparisons is easy, considering that some but not all of the figures that enter the public sphere include financing charges, design and consulting fees, and land acquisition costs - or even if they all do, they might not reflect the same accounting methods. "You really have to avoid confusing hard costs and soft costs," says Bill Palmer, vice president of business development in Hunt Construction Group's Indianapolis office. "A lot of times people quote numbers, and they're not pure construction costs - those numbers are pretty erroneous, I'd say, from what the true costs are."

But with the figures quoted these days nowhere near Marlins territory, it's questionable whether differences in accounting could actually account for the huge jump in costs. The Minnesota Vikings' Legislature-approved new home carries a price tag of $975 million, and that budget doesn't include making its dome retractable (which the team's owners, who would have to pay the $50 million it'd cost to do it, are still considering). The 49ers' new digs, currently being dug in Santa Clara, Calif., will have 68,500 seats, 165 suites and a green rooftop deck (green as in, solar panels and herbs to be used for onsite food prep), and is budgeted at $1.2 billion. Two groups of Angelenos are vying to become the preferred developers of a stadium to serve as the home field of a yet-to-be-attracted NFL franchise; one site, near City of Industry, would bear an $800 million price tag if it were built, as first conceived, with two-thirds of its stands on a hillside, thereby saving greatly on expensive steel and concrete. The other (downtown) location, so far along in its planning that it has already attracted Farmers Insurance as a title sponsor, is budgeted at $1.2 billion and includes 75,000 seats and a retractable roof, even though it purportedly never rains in southern California.

Macroeconomics might suggest that prices could fall during recessions, as the supply of materials suddenly outstripped demand. Unfortunately, it's not so simple: Beginning in late 2008, for example, credit dried up, consumer purchases dropped like a stone and manufacturers cut back on production - and businesses from all sectors, from architects to construction companies to producers of raw materials, laid off workers. Prices of raw materials did, in fact, continue to rise as huge overseas growth kept demand high (particularly for steel), but as the world economy has since faltered, prices have stabilized (although they haven't dropped).

Kent McLaughlin of Kansas City, Mo.-based 360 Architecture, which partnered on the design of the $1.6 billion MetLife Stadium, claims a "tiny economic brain," but believes that widespread self-interest is a major factor. "I think it speaks to the way Americans do business," he says. "With the economic downturn, companies decided they needed to continue to make the same money they were used to, so if you used to pay $85 for each stadium seat, now it's $105 or $115 rather than, say, $80. It's the make-believe money we all operate on. Your Chrysler car hasn't gone down in price even after the government bailout, and they're making money hand over fist. What the heck?"

McLaughlin's surprise is more than matched by widespread sticker shock within the sports industry and among the public at large. It doesn't help that when insiders make assertions about the primary cause of inflation - more on this below - inevitably more than one recent stadium fails to fit the theory. Consider the various contributing factors which, together, might help explain how hundreds of millions morphed into billions:

Cowboys Stadium is, however, in a league of its own with regard to size. While the most recent stadiums are generally bigger than the previous generations of buildings, the difference isn't vast - on the high end, an increase more on the order of 20 to 30 percent. For example, 1.9-million-square-foot Reliant Stadium cost $352 million in 2002; built six years later for $720 million, Lucas Oil Stadium comprises 1.9 million square feet. Slightly older pro football stadiums ranged from 1.1 million square feet (LP Field, 1999) to 1.6 million square feet (M&T Bank Stadium, 1998), while the even older and presumed-obsolete Georgia Dome (1992) contains 1.6 million square feet of space. Moreover, the planned stadiums aren't much larger than that - the 49ers' stadium in Santa Clara will be 1.85 million square feet, while the Vikings' proposed stadium as currently configured would be 1.7 million.

Among baseball stadiums, much has been made of new Yankee Stadium's 63 percent jump in square footage over its predecessor (which opened in 1923), but there has hardly been a huge increase in size over the past decade. Citi Field (1.2 million square feet), Nationals Park (1.1 million) and Target Field (1 million) aren't significantly far off from earlier venues PETCO Park (2004, 1.3 million), PNC Park (2001, 970,000) and AT&T Park (2000, 967,000) - about 15 percent larger, as a group.

• Premium zones. Seating capacities are smaller, but the footprints are bigger. What there's more of is premium space that includes suites, club sections, bars, restaurants and other retail establishments. "We talked to a baseball owner about six months ago who's looking at renovating a venue, and the plan was to add 25 restaurants and bars," Palmer says. "I mean, nobody went to a bar inside a stadium 20 years ago. You went to a game and then you left right after. They try to keep you captured in these venues; they give you as much stuff to do there as you possibly can, so you'll spend more money there."

"The building is just a different building than it used to be," says Dan Mehls, director of project development with Mortensen Construction, which built Target Field. "Fifteen, 20 years ago, it was just about having a big volume of space to watch games. Now it's about the whole fan experience. There are two $10 million video boards instead of one $500,000 video board, and big club areas where 3,000 people can sit in a big fancy restaurant. It's just night and day."

• The finished product. A higher level of finishes is apparent throughout the newest stadiums. "In basic, municipal-style venues there's a lot of exposed structure, block walls, and then the owner will spend money on the entrance experience and premium areas like suites, but after that it's all exposed structure," says Mehls. "Pro team owners want to cover up all the structure with high-level finishes and expensive technology, so that's a big variable."

"There are a greater number of high-end finished spaces, the team areas are more extensive," adds McLaughlin. "What's being offered to the patron is of better quality. Instead of a stainless-steel or wood counter, now you see quartz and granite, things like that. Those things cost 'x' dollars a square foot more, and it adds up."

McLaughlin pauses, considering MetLife Stadium.

"MetLife didn't have one particular thing that stands out in my mind, but there was a lot of keeping up with the Joneses: If you have four giant scoreboards, I have to have four giant scoreboards," he says. "Technology in general has changed, where 80,000 people using cell phones now drives owners to provide more equipment, more wireless access points. MetLife just added 500 more access points than we originally programmed only six years ago, because the demand is there. We can spend $100 million in technology on a job, and then have to add another $5 million to it just to keep up with patrons who want to be able to get apps on their phone and call grandma from the game."

• Indoor-outdoor. Retractable roofs seem like the biggest 'keep up with the Joneses' of them all, given that many teams appear to build them without a clear need to play games both indoors and outdoors. And they can be a very expensive item, both because of the roof itself - its panel configuration and the technology required to open and close it - and the additions to the stadium structure and mechanical systems that its use requires. "Open-air buildings have a smaller amount of exterior skin, and they're completely missing 80 percent of the mechanical systems needed to air-condition the space," Trubey says. "That's a big chunk of change right there."

But, Trubey is quick to add, technological improvements have limited the costs associated with certain types of roofs. "Several things influence the cost of retractable roofs: the size of the opening, the weight of the structure and the type of mechanism that you use. It's not a straight-line equation," he says. "For instance, the roof opening of Lucas Oil Stadium is larger than the one at Reliant Stadium, but it was a lot less expensive because for reasons of building character we had structure going through the opening."

• Structural materials. The proliferation of roofs, retractable or fixed, and the expansion of building footprints have combined to add to the amount of steel and concrete used, which means higher materials and (especially with regard to concrete) labor costs. And, as McLaughlin says, "Steel just goes up in price, it doesn't come down. Everything keeps creeping up."

• Site work. Costs centering on building sites should be more or less stable from one decade to another, but many of the newly built or planned stadiums have been in tricky locations requiring extra dollars. Don Dethlefs, CEO of Denver-based Sink Combs Dethlefs, mentions more-stringent seismic requirements in California as adding to the costs of stadiums there (and in Las Vegas and a few other locales), as well as factors that influence costs on a case-by-case basis. Target Field in Minneapolis, for example, was "wedged in by viaducts on a very tight site," he notes, while even a new Vikings stadium located on available land next to the Metrodome will require a phased demolition and construction that will surely add to costs there. Added to which, Dethlefs says, "Even the spaces around the buildings are getting more lavish; people are spending way more on plazas and other finished outdoor spaces. You take an NFL stadium these days, and you see a much larger perimeter, paving and artwork - you can end up spending millions just on the site."

• The coastal effect. MetLife Stadium was built on available land and doesn't have a roof. "Yeah, but that's the East Coast," Mehls interjects. "It's a whole different world than the rest of the country." How much of a different world? "It's the most expensive place to build," Dethlefs says. "When you add New York into the equation, it skews the numbers by 30 or 40 percent. Los Angeles is the same, and then you add all the seismic requirements. On the coasts and in the Big Three cities in particular, you're definitely going to pay more per square foot."

"In New York, we used to double the price," McLaughlin adds. "Now it's triple the price - and the San Francisco area is similar."

• Local flavor. See above, but don't expect anyone to talk very freely about it. Cities with large concentrations of union labor in particular get a bad rep. "Dealing with three or four union trades definitely has an impact," McLaughlin says. "You need somebody to make it, somebody to drive it, somebody to unload it off the truck, somebody else to erect it."

Similarly, John Hutchings, an HKS principal, cites cheap labor as a reason that Cowboys Stadium was "such a bargain," preferring to focus on the stadium's $850 million hard cost. But, he says, the issue isn't so much unions - even with some estimates tabbing union labor as adding anywhere from 10 percent to 30 or 35 percent on the high end - as it is with wage rates that vary regionally.

On this, McLaughlin concurs. "It's just the cost of doing business, as generic as that sounds," he says. A construction manager with ongoing business interests in the Northeast is willing to be more specific, though off the record: "In a major metropolitan area, it's what it costs to get projects approved and permitted, street and lane closure fees - fees for everything - as well as all the different levels of consultants that get added to these kinds of challenging projects. There are layers of costs, layers of inefficiencies that the rest of the country doesn't experience, and there's a premium associated with all of that."

Were you to add up all the costs associated with each of these elements, it probably still wouldn't explain the final cost of most of the stadiums mentioned here - with the possible exception of Cowboys Stadium. ("You see where they spent the money in Dallas," says Dethlefs. "It's obvious.") Many designers and contractors sound just as unsure as laypeople about where the money has gone. "I don't know that we've seen an exponential increase in per-square-foot cost basis," says McLaughlin. "The difference is millions, not hundreds of millions."

Palmer says the shock felt by the public is more than understandable, since team owners themselves are often shocked by the price escalation. "What happens is one team owner comes to talk to another team owner, in Indianapolis, say, and he wants to put a venue in another city just like the one he sees here," Palmer says. "The owner in Indy says, 'Well, I built that 10 years ago for $200 million,' and the second owner says, 'Well, I'll just pick that up and put it here, put in an escalation factor.' You take one stadium someplace else and it's more than double, and you're shocked. Kind of typical in our industry, that people don't realize there's such a huge disparity between Florida and New York and Minneapolis and Kansas City. Every project is unique; you can't just plug and play."

But then, Palmer asks, should rising prices really surprise anybody?

"The numbers are mind-boggling, there's no question about it," he says. "But whoever thought we could top the Superdome, the eighth wonder of the world when it was built? It just shows you that what was state of the art then is archaic now."