Aspiring Olympians get educational opportunity at NMU training center.

By now, the athletes who will represent the United States at next month's Summer Olympics in Sydney, Australia, have the bulk of their preparation behind them-specialized training at the expense of nearly every other personal interest. For many, such dedication means dropping-or at least suspending-any pursuit of secondary or higher education.

But others among this year's American contingent will arrive Down Under by way of Michigan's Upper Peninsula, where they have honed both athletic and academic skills at the nation's only U.S. Olympic Education Center. Located on the campus of Northern Michigan University, the USOEC requires aspiring Olympians who live there to also learn there. Nowhere in the United States is it easier for high school and college-age participants in Olympic sports such as Greco-Roman wrestling and luge to continue their education while preparing for the Games.

"Athletes in swimming, track and field, volleyball, basketball-common sports competed at the NCAA level-have a nice progression. They can work from high school to college and on up to the Olympic team, continue going to school, get their education, and they don't miss a beat," says Jeff Kleinschmidt, USOEC program director. "But what about those poor athletes in biathlon, boxing and short-track speed skating? For 100 years, basically, they were forced to make a decision-either continue going to school and quit their sport, or continue in their sport, try to make the Olympic team and drop out of school."

That began to change in 1985. Following a 20-year lobbying effort by NMU and a booster group of local businesses, the U.S. Olympic Committee established a training center in the modest Michigan college town of Marquette (population 23,000), which offered a community luge track and ski jump and upwards of 300 inches of snow during any given winter. The unique designation of Olympic Education Center followed four years later to distinguish the USOEC from training centers in Colorado Springs, Colo., and Lake Placid, N.Y. (a third training center has since been added in San Diego).

To be accepted into the USOEC, athletes must exhibit not only requisite skills in their respective sports, but also the academic aptitude to succeed at NMU or, in fewer cases, at nearby Marquette Senior High School. Once accepted, athletes are required to carry at least three course credits, though many take full loads of 12 to 16 credits during off-season and summer months. For athletes who rank in the top 15 nationally in their sports, the university waives out-of-state tuition fees, and room and board is paid for by the USOEC. Additional athletes may receive partial financial assistance, and others choose to pay their own way for the opportunity to live and train in Marquette. Current resident programs include boxing, Greco-Roman wrestling, luge, biathlon and short-track speed skating. The U.S. Ski Team is likely to establish a resident program for Nordic skiing this fall, according to Kleinschmidt, who adds preliminary discussions are under way with USA Badminton and USA Weightlifting.

The USOEC's $950,000 annual operating budget includes $500,000 from the State of Michigan, another $200,000 from an Olympic license plate program in Michigan, $130,000 from the Colorado Springs-based USOC, and the balance from corporate contributions, merchandise sales and tuition collected from the USOEC's non-scholarship athletes.

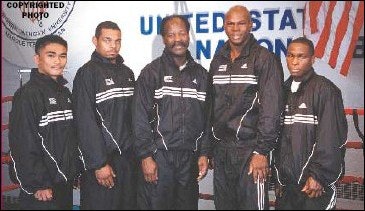

The center's popularity is especially evident in its boxing program, which boasts an exclusive and permanent training facility converted from an old NMU field house, as well as instruction by Al Mitchell, the 1996 Olympic boxing coach. Of the 100-plus highly ranked boxers who apply each year to train at the USOEC, five or fewer are accepted, according to Kleinschmidt. As one of the fortunate few to get in, Vernon Forrest brought two goals with him to the USOEC: to become the first member of his family to finish high school and to box at the 1992 Summer Olympics. He did both, taking classes day and night in the fall of 1991 to meet his own graduation deadline of January 1992 before heading for Barcelona, Spain, as a member of Team USA. "He didn't medal there, but just the fact that he made it with everything else he was going through at the time was a tremendous accomplishment," Kleinschmidt says.

Such stories serve as inspiration to the entire student body, according to NMU President Judith Bailey, who says she would like to see the classroom interaction between traditional students and aspiring Olympians spill into social settings to a greater extent, though training schedules make it difficult. Even so, the mere presence of the USOEC on campus has been a selling point for the university. "It's a niche for us," Bailey says. "Our Olympic athletes come from all over the United States, and that has broadened our student draw. We're a regional university, and the center has increased our diversity of thinking and exposure of our traditional students, who predominantly come from small rural areas, to students who've had various life experiences."

Take Brian Viloria, the reigning world light flyweight champion and a favorite to medal in Sydney as one of four USOEC residents on the 12-member U.S. boxing team. A broadcast journalism major as a freshman at NMU, Viloria came to Marquette from his native Honolulu, Hawaii. "You talk about culture shock," says Kleinschmidt. "But he moved here, enrolled in school and did a great job. He just knew that this was the place he had to be to get his best shot at making the Olympic team."

Kleinschmidt says it's difficult to determine how many USOEC athletes actually go on to receive degrees, since many return home after competing in the Olympics. He estimates that half earn a degree, either high school or college, while residing at NMU.

For many of the athletes, any education is a plus. "I think that's a great benefit for all the sports, but especially so for boxing, which is overcoming a perception, and maybe a reality as well, that most of its athletes come from environments where education hasn't been a high priority," says John Smyth, director of all USOC training centers and a former college professor.

Cathy Turner, a four-time Olympic medalist in short-track speed skating, took the long route to a college degree. By the time she graduated from NMU in May 1991, Turner's college career had spanned 11 years-with stops at six different campuses-thanks to an offand-on relationship with her sport. Her arrival at the USOEC to train for the 1992 Winter Games in Albertville, France, finally brought synergy to Turner's twin pursuits. "I could refocus on my schooling and get my degree," she says. "That wouldn't have happened any other way."

She could also refocus on speed skating, following a layoff of nearly nine years. A typical day for Turner at the USOEC involved sprinting to classes in her skating tights in between a pair of three-hour workouts held at an on-campus rink. Her schedule and age (30) made Turner a student like few others. "I felt like kind of a unique college student," she says. "It definitely felt different. I did have friends, but it was different in that my focus was obviously skating."

Turner carried 16 credits during her final semester while training for her first of three Olympic appearances. She received straight A's. Months later, she would garner gold in the 500-meter event and silver as part of the 3,000-meter relay at Albertville, sharing much of the credit with an NMU sports psychologist who made the trip with her. Later, at the 1994 Games in Lillehammer, Norway, she would repeat her victory in the 500 and earn bronze in the 3,000 relay.

For all its success, the USOEC is not likely to be duplicated in another college town anytime soon. The USOC's Smyth, whose 30 years in higher education included teaching health and physical education, says NMU's willingness to share athletic facilities with prospective Olympians may be hard to find on other campuses. For example, NMU's hockey team now skates on an Olympic-size ice sheet in the recently constructed Barry Events Center, which was designed to also accommodate short-track speed skaters. Kleinschmidt believes the USOC may view additional Olympic Education Centers as a strain on its limited resources and on the value of the Olympic-rings mark. Turner, for one, sees a need to expand the concept of combining Olympic preparation with the pursuit of education.

"I have teammates who won two Olympic medals on the relay team with me, and they went home and ended up working in an ice cream shop. I just don't think that's right," says Turner, who now works as a motivational speaker. "I really think that wouldn't have happened had they taken advantage of facilities like those at NMU, Marquette and the USOEC."