After enduring decades in relative obscurity, athletic programs at historically black colleges and universities are securing their place at the sponsorship table

Three hundred million dollars. That figure represents sports marketers' estimates for first-year sales of Russell Athletic's new product line, which features logoed apparel of 30 of the 34 historically black colleges and universities (HBCUs) that make up the Mid-Eastern Athletic, the Southern Intercollegiate Athletic and the Southwestern Athletic Conferences.

Available starting this fall, sports fans everywhere will be able to purchase replica sportswear of HBCU players and coaches, or "throwback" jerseys of HBCU athletes from the past - men like Lou Brock, Deacon Jones, Steve McNair, Jerry Rice and Walter Payton. "Russell has created a whole new division just for this business," says Victor Pelt, president of New Vision Sports Properties, the Oakland, Calif.-based, African-American-owned sports marketing firm responsible for negotiating the Russell/HBCU contract. "We're talking $60 million to $70 million in sales - just out of the campus bookstores."

"This deal was born out of our company's strategy to improve corporate diversity," says Kevin Clayton, Russell Athletic's vice president of diversity. "This goes beyond race and gender issues. From a marketing standpoint, we wanted to know what opportunities were out there, if we used the unique skills of our employees."

In return for five years of exclusive apparel licensing rights, Russell will pay the three HBCU conferences 10 percent royalties on apparel sales, as well as provide the men's and women's basketball and soccer, football, baseball, softball and volleyball teams at the 30 member schools with free uniforms, performance and casual apparel, and athletic equipment. (Tennessee State University, an HBCU affiliated with the Ohio Valley Conference, is also part of the deal.) Until now, it had been common practice for HBCU athletic programs to purchase all of their own equipment and uniforms, usually at retail cost.

"You could go to Foot Locker and pay less for a jersey than what these guys were paying," says Pelt. "This is why: A guy from Nike or Reebok would go into a locker room and give a duffel bag of golf shirts and hats to an assistant coach or equipment manager. When the guys from Russell first went to these schools and said, 'Let's make a deal,' the coaches would say, 'We can't. We already have a deal with so-and-so.' "

Unscrupulous business practices among athletic outfitters were as much to blame for keeping HBCU athletic programs in the financial dark ages as was a lack of awareness among school officials. "Right now, we're in the process of renegotiating a soda deal for the three conferences," Pelt continues. "The soda companies have all these schools fragmented, and they've done it on purpose. For example, one company touts its philanthropic contributions to HBCUs. But between all schools in the three conferences, it gave no more than $300,000. We're now talking about doing a deal in the mid-seven figures. HBCUs had become so self-sufficient, so used to doing without. They didn't think it was possible to get more. A school might've done a $20,000 deal, but didn't realize it could've gotten $2 million. That's the real story."

Indeed, the Russell contract has a much greater impact than that of simply providing HBCU athletic programs with free gear. Not only is the sponsorship the first big-money deal for many of these schools' athletic programs, it is also the first time they have joined forces in an effort to achieve financial security.

"Times are changing, in that all institutions understand there is a common tie that binds us, greater than the things that make us different," says SIAC Commissioner William Lide. "Our philosophy is to pool our resources, rather than be 12 individual schools. Brokering deals - not only as a conference, but collectively as conferences - has provided us with increased buying power, exposure and financial gain."

The fact that HBCU athletic programs are now proving to be marketable products on a national scale doesn't surprise companies already familiar with HBCU athletics. Urban Sports and Entertainment Group, a Cornelius, N.C.-based sports marketing firm that since 1992 has helped organized basketball tournaments, marquee football games (or "classics") and other HBCU special events, is one of those companies. Micah Fuller, Urban Sports' vice president of business development, has been there for the duration. "I think I've done a combined 168 football and basketball games," says Fuller, adding that, all told, his company has secured for HBCU athletic programs approximately $30 million in corporate sponsorships.

The list of "blue-chip companies," as Fuller calls longtime sponsors of HBCU athletics, is quite impressive: Coca-Cola, Anheuser-Busch, the United States Marine Corps, Food Lion. "These are companies that support HBCUs year in and year out," he says. "We have great sponsors. Ford, for example, started off with a small sponsorship. Now it's the title sponsor of the Detroit Classic and the Ford Black College Football Road Trip, and is the presenting sponsor of the Bayou Classic."

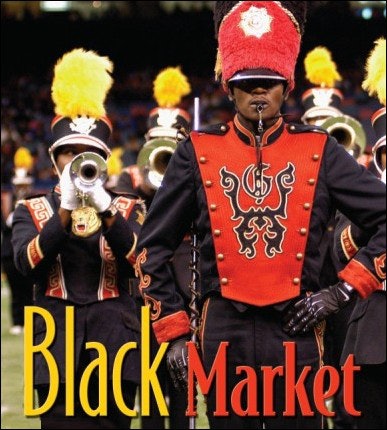

Special events such as the Bayou Classic, the long-running annual event that pits the football teams and marching bands of Grambling State and Southern Universities against each other before tens of thousands of fans at New Orleans' Superdome, are almost single-handedly responsible for putting HBCUs on the college sports map. "We play these classics all over the country, in cities like Detroit, Indianapolis, Kansas City, New York and San Diego," says Dennis Thomas, commissioner of the MEAC, home to 11 schools along the Atlantic coastline. "In Division I-AA, no other programs can put 50,000 people in the stands."

Indeed, well-attended football classics helped the SWAC - which, like the MEAC, competes at the NCAA Division I-AA level - lead the division in average attendance for all 26 years the NCAA has recorded such figures. In 2003, the SWAC averaged 12,083 fans per football game, or 39 percent more than the division-wide average of 8,684.

Football classics have also been good for MEAC schools. Florida A&M, which averaged 21,323 fans per game despite playing only three contests at home (four of the school's 11 regular-season games were classics, played at neutral sites), had the third-highest average attendance among Division I-AA schools. (The SWAC's Southern University, with 19,732 spectators per game, was fourth.)

Meanwhile, basketball is the sport that drives the Central Intercollegiate Athletic Association - a fourth major HBCU conference, featuring 12 NCAA Division II member schools in Maryland, Virginia and North Carolina. This past spring, the weeklong CIAA tournament, which hosts both men's and women's play, drew 104,500 fans, sold $1.82 million in tickets and generated an economic impact of $11.5 million for its host city, Raleigh, N.C. The CIAA tournament even boasts final session attendance figures comparable to those seen at basketball tournaments of much larger leagues, including the Atlantic Coast and Southeastern Conferences. "The CIAA tournament is the third-largest in the country," says Fuller, "and the largest of the HBCUs."

But outside of the South, the CIAA basketball tournament is relatively unknown. Likewise, the football classics of the MEAC, SIAC and SWAC - while wildly popular among African-American football fans (many hailing from Southern states) and HBCU alumni and students - have yet to establish a foothold among mainstream college football fans.

More important, despite having broken down a few doors, HBCUs have yet to move up in priority on the marketing budgets of many corporations with the power and influence to thrust those schools' athletic programs into the national limelight. "The University of Michigan gets $90 million from Nike. Do you know what HBCUs could do with that money. Or when you see the kind of money Dr Pepper throws into the Big 12 championship game, it's frustrating," says Fuller. "It's only a matter of time before companies realize the potential here."

Many already have, says Clayton. "I speak at a number of diversity conferences around the world, and there are all kinds of companies that want to find out how they can get into HBCUs."

Many mainstream companies, though, face a steep learning curve. It was five years after the creation of its diversity group before Russell Athletic was prepared to approach the HBCUs about a sponsorship opportunity. "We had been encouraged by our CEO to look at non-traditional markets. Although we had an interest in HBCUs, we did not have a strategy to address their unique needs," says Clayton, adding that for Russell execs, making efforts to identify with their prospective clients was just as critical as convincing them of the quality of their product. "In establishing our diversity department, we started to realize that developing personal relationships and trust with university presidents was important."

If Russell, a company based in the South for more than 100 years and employer of a number of HBCU graduates, had those hurdles to clear before HBCU officials accepted its sales pitch, then other companies hoping to get in the door will certainly have to do their homework. "Corporations are saying, 'We knew there was a University of South Carolina, but we didn't know there was a South Carolina State University,' " says Pelt of the MEAC school. " 'We didn't know that South Carolina State had a football team, let alone one that could put 50,000 people in the stands for a classic. And, by the way, what's a classic?' "

To a potential corporate sponsor, an HBCU classic represents an opportunity to advertise its products before a live captive audience comparable in size to those attending major post-season bowl games (not to mention a televised audience of up to 30 million homes, thanks to cable TV's Black Family Channel, an Atlanta-based network that broadcasts, among other programs, HBCU sports in 3,700 cities in 47 states).

Often billed as family affairs, football classics are known for their ability to attract large crowds. Last September, the Detroit Football Classic drew an announced crowd of 54,500 to the Detroit Lions' Ford Field to see Alabama State University defeat Florida A&M 38-22. At the Southern Heritage Classic in Memphis, Tenn., 52,603 fans witnessed Tennessee State's 44-14 victory over Jackson State (the two previous years, the game had drawn only 38,000 and 26,000 fans, respectively).

Also that month, the first annual Las Vegas Classic, which featured the Southern University Jaguars and the North Carolina A&T State University Aggies, drew to Sam Boyd Stadium nearly 21,000 paying fans and an estimated 6,000 to 8,000 more who simply tailgated outside the stadium. A halftime Battle of the Bands competition was followed by a five-minute, $30,000 fireworks display. The night before the game, activities included a "Vegas After Dark" party with a fashion show and a performance by comedian Steve Harvey, while a concert by the Neville Brothers served as the main attraction of Saturday's post-game party. The weekend also featured appearances by former Iraqi prisoner of war Shoshana Johnson, singer Gladys Knight, radio personality Tom Joyner, the NBA's Karl Malone and Dale Davis, and retired heavyweight boxer Lennox Lewis.

For their participation in the Las Vegas Classic, each school received a $150,000 payout and was reimbursed for all travel expenses incurred by its football team and marching band. "That's the way to do a classic," says Fuller, whose company co-hosted the event.

Unfortunately, for every group of successful classics, there are just as many that suffer from mismanagement. (Currently, none of the conferences actively regulates football classics, leaving such affairs in the hands of the participating schools.) Without many rules or restrictions, virtually any event promoter can organize a football classic. And according to Pelt, it's fairly easy for greedy promoters to set themselves up to receive a hefty profit and leave the schools with little to show for their participation.

"The way the classic system is set up, you and I can start a classic. Say that on Nov. 1 in Oakland, you're going to have the 'Oakland Soul Train Classic,' " he says. "So you go out and negotiate with the city the stadium contract and ticket sales tax. Then you'll get two schools - let's say Grambling State and Howard - and you'll pay them $125,000 each, but both schools have to pay for food, lodging and transportation for their band and team.

"If you sell 65,000 tickets at $50 apiece, which covers the taxes you owe the city, you just made $2.75 million in gross revenue. Out of that you're paying $250,000 to the schools, and you're walking away with $2.25 million, after expenses. Say you sell only 40,000 tickets - well, take that shortfall out of the schools' money, and give them only $90,000. If their travel bill just happens to be $89,952, they just went home with about $50."

The sad truth is that event promoters have been structuring deals like these for years. Some athletics officials have been afraid to ask for better contract terms, says Pelt, because they fear "the promoters will get upset."

Fuller, too, has seen his share of classic blunders. "I suppose, as in any sort of business transaction, there are deals that go bad," he says, adding that sponsorships are just as crucial to the success of a football classic as are ticket sales. "You can't depend on ticket sales alone. I've seen promoters overestimate attendance. I've seen schools not get their checks. I've seen classics get cancelled the weekend of, simply because the promoters didn't have enough money in the bank to pay their bills."

To avoid such embarrassment, Pelt has his own suggestion for HBCUs. "What they should do is fire that promoter and use their own in-house promoter," he says. "If you did one classic and made $2.4 million, that's $1.2 million per school. Your budget is made for the next three years."

It could be some time before the majority of HBCU athletics officials feels so emboldened. The days of segregation and Jim Crow may be well in the past, but Pelt has the feeling that in the boardroom some HBCU officials still view themselves as inferior negotiators. "Whether we like it or not, white people like doing business with people who look like them. However, black folks like doing business with white people because it makes them feel elitist," says Pelt, who is African-American and works full-time as vice president of corporate sponsorships for the NBA's Golden State Warriors. "But when I walk into some meetings with HBCU officials, they look at me and say, 'How do you know what you're talking about? You can't know more than us.' Well, I've been doing one thing all day, every day at a high level for the past 15 years."

Pelt says he started New Vision Sports Properties as a part-time endeavor with the intention of helping HBCU athletics programs "properly position themselves" to get more out of Wall Street. "It's not about Victor. It's not about New Vision. It's about these HBCUs. It's an effort to educate these schools on what's out there," he says. "I'm just a conduit, a messenger."

Apparently, the message is getting through. The MEAC, SIAC and SWAC commissioners - all installed within the past three years - have issued mission statements that are curiously similar and complementary. Among the commissioners' immediate goals, in so many words, are to 1) develop solid corporate sponsorship programs, 2) improve the marketing of their respective conference brands, 3) increase TV and media exposure, and 4) improve the student-athlete experience. As SWAC Commissioner Robert Vowels puts it, "We're looking at the big picture."

"When I took this job, there were certain things I had to be assured of," says the SIAC's Lide. "One, there had to be significant partnership with the conference presidents. And two, the athletic directors had to be willing to better themselves and their programs, to move forward rather than remain stagnant."

To show just how serious HBCUs are about moving in a new direction, consider the events that unfolded recently at Grambling State University, a school that for many casual sports fans serves as the symbol of HBCU athletics. In February, well-respected head coach and former Super Bowl MVP Doug Williams left the Tigers football program after six seasons at its helm to join the NFL's Tampa Bay Buccaneers as a personnel executive.

Weeks after his departure, it was reported that Williams, who excelled at Grambling State both as a player under legendary coach Eddie Robinson in the early 1970s and later as Robinson's successor in the '90s, left because of his "exasperation over the school's inability to deal with the program's needs."

"There was never any action on things I asked for," Williams told Mary Foster of the Associated Press. "Nobody but me seemed to want to get things done."

Among the items Williams requested in a memorandum sent to athletic director Albert Dennis III just months before his resignation: approval to hire a fulltime defensive coordinator, at a salary ranging from $30,000 to $35,000, and either a part-time coach or two graduate assistants; money to purchase medical and office supplies and to maintain the football field, practice field and support facilities; and a second weight room for non-football student-athletes. "It ranged from very simple things like making sure the fields were kept up and taking care of the front of our building to adding a seventh coach," Williams said. "Since I've been there we've been a coach short. I wanted another assistant the same as everybody else has."

According to Williams, his proposal went unanswered for 20 days, after which he decided it was time to leave his alma mater.

By July, Grambling State had not only lost its head coach, the school had also lost its athletic director. On July 1, his first official day at work, incoming university president Horace Judson asked Dennis to step down. "The athletics department is a vital component of the university and is a priority in my vision for strengthening Grambling State University," said Judson in an official statement.

Those close to the Tigers athletics program, while slightly surprised at the new president's quick action, agreed with the move and anticipate Dennis' successor will be a savvy marketer and an aggressive decision maker. "It's my hope that the replacement is someone who will be upwardly mobile and someone who can realistically move the athletic department forward," Ralph Wilson, president of Grambling State's fan-based Quarterback Club, told the Monroe (La.) News-Star.

Not everyone is convinced that HBCUs are entering a new era of financial fortune, or even that the schools are in need of a drastic athletics policy overhaul to achieve fiscal success. Officials at Morgan State and Howard Universities, for example, opted not to participate in the tri-conference revenue-sharing deal with Russell Athletic. By doing so, Pelt estimates that each school is passing up on $1 million a year. (Morgan State athletics officials failed to respond to AB's interview request.)

Meanwhile, Clayton has his own suspicions as to why the schools refused to join the sponsorship party. "It's unusual for a company to do a deal of this magnitude with this many conferences," he says. "I would say that Morgan State and Howard thought it was too good to be true."

Fuller believes he understands why those schools hesitated. He suggests that the MEAC, SIAC and SWAC commissioners need more experience in their respective posts before potential corporate sponsors take them seriously. "They'll need more seat time, maybe five, eight or 10 years," he says. "You don't need to be the largest athletic conference to be successful. What you need is to surround yourself with a team of great people."

But Pelt says that corporations are already taking his clients seriously, citing major sponsorships with Russell Athletic and Chrysler Group. (The MEAC, SIAC and SWAC signed a multiyear agreement allowing the corporation to advertise its Chrysler, Jeep ® and Dodge brands at more than 80 football and basketball games televised on the Black Family Channel, as well as in-venue signage, dealer hospitality and inclusion in a wide variety of print and web-based media outlets.)

Securing multiconference sponsorships has required that HBCU athletics officials get accustomed to setting aside their long-standing rivalries in favor of cohesive business relationships. In its dealings with Russell, Chrysler and the other conferences, SWAC officials "looked at the assets we had and tried to marry them up," says Vowels. "At the end of the day, Russell and Chrysler want to sell more product."

"It's a win-win move for us to participate," Clayton says. "This is all part of our strategy to enhance our name. This deal falls right in line with the goal to increase our market share."

The HBCUs' strategy is also paying dividends. "To me, the definition of business is working together to get a resolution so that we can both come away with what we want," says Pelt. "Somewhere along the line, the HBCUs realized that to get anywhere, they'd have to be as one in the business setting, but be as competitive as they could on the field."