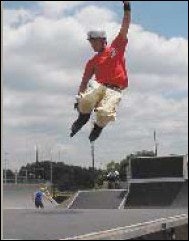

All across America, communities are finding ways to involve kids in the process of building skate parks-and consequently, keeping skaters off the streets.

This much is clear: Fayetteville, Ark., will eventually have a skate park for its increasing number of resident skateboarders and in-line skaters. Park and recreation officials just don't yet know the size of the park, its cost, its features or even its name. In fact, they only just recently determined its location-in an existing city park where parking and plumbing are already available. But officials are adamant about doing this thing right, which means gathering as much input as they can from skate park designers and skaters themselves. Eric Schuldt, parks development coordinator for the city's Parks and Recreation Division, has seen too many neighboring communities build inadequate parks. Fayetteville doesn't want to make the same mistake. "If we're going to spend the money, let's bring in a firm that's built skate parks before," Schuldt says. "If certain design elements aren't right, kids are eventually not going to skate there. And if the kids are more than willing to express their views about how it should be done, this should be something they are a part of-not just something the city slaps together." Bravo, say skating industry leaders. By combining local and professional input, they say, most communities can develop a feasible plan to build a skate park that will be accepted and used by residents for years to come. The skaters-many between the ages of 12 and 16 who've already been shut out by local ordinances banning them from downtown sidewalks, college campuses and other public places-can tell local officials what they want in a park. But qualified builders with experience creating skate parks will make sure the skaters' requests aren't out of line with budgets, space requirements and other restraints. "Kids talk in a different language," says Linda Rice, owner of Naples, Fla.-based Sanctuary Skate Parks USA, a turnkey skate park operating company with four facilities in the Southeast. "And half the time, the adults at city hall don't even understand what they're saying." Or listen to what the kids are saying. One city in Kentucky spent $40,000 on a skate park that became a white elephant, largely because local officials did not keep skaters involved in the design process. The ramps were built to be durable and safe, but they weren't inviting to skaters. And there are plenty of skaters out there. More than 32 million Americans, ages 6 and up, have strapped on a pair of in-line skates at least once, according to the Sporting Goods Manufacturers Association, and more than seven million have propelled themselves on a board. These two activities, respectively, have become the first and third most-popular extreme sports in the United States - statistics not lost on the folks at the Skate Park Association of the United States of America. More than 600 skate parks have been built during the last two years or are currently under construction, association officials say. And numerous communities are in the early stages of planning even more new facilities - at or adjacent to existing parks and community recreation centers, inside new or unused buildings and in abandoned parking lots. From West Palm Beach, Fla., to Santa Barbara, Calif.-and seemingly everywhere in between-outdoor and indoor skate parks are dotting the nation's landscape. While many of the same elements (ramps, steps, benches and curbs) dominate these parks, each facility is distinct enough to meet the needs of that community's skateboarders and inline skaters, as well as BMX riders who share the facilities with their skating brethren. A small percentage of new parks even boast a nearby roller-hockey rink, complete with either portable or permanent dasherboards. Today's typical skate parks consist of wooden or more-expensive concrete obstacles, and construction costs (excluding land) typically start at $100,000. They're public (although some charge per-session fees), and they have nearby or on-site rest rooms, parking lots, spectator areas and vending machines. Some include a pro shop where accessories, concessions and other items are sold. The majority remain unfenced and unsupervised, meaning that a staff member is not always present, so it's up to the skaters to police themselves. This keeps insurance costs in line with other types of municipal parks, builders say. Adding supervision puts operators in another insurance bracket. Sanctuary Skate Parks USA attempts to solve the insurance quandary by being the only skate-park company to offer communities turnkey facilities designed with local input and built, operated, maintained and insured by Sanctuary staff. The community receives a percentage of the park's total gross revenues from fees, rentals, sponsorships and sales. If today's skating surge sounds familiar to park and recreation veterans, it should. Back in the 1970s, hundreds of private and public skateboarding facilities were built in the United States, according to the International Association of Skateboard Companies. But many of them were uninventive and featured cement bowls and other effects that echoed the backyard pools, drainage pipes and ditches that skateboarders frequented at the time. One skate park builder today likens the shapes of early facilities to "ashtrays." Because of the threat of liability claims against private owners of those parks, many of them shut down by the mid- '80s, forcing skaters to go elsewhere to develop their skills-which now included lifting their boards off the ground and onto benches, curbs, walls, steps, handrails and other urban elements. By the late-'80s, "skaters were often perceived as aggressive urban guerillas out to thrash their local community as they ground their way about town," according to IASC's Web site. More recently, though, skaters-both those on boards and in-liners-have been recognized in many communities as constituents with recreational needs just like everyone else. Skaters, whose ages range from the single digits on into the 30s and beyond, have cleaned up their image, skate park builders say. Beneath the piercings, baggy pants, colorful T-shirts and unconventional haircuts are some of the most intelligent and motivated kids community officials are likely to encounter. "Of all the user groups, skaters are the easiest to work with," says Steve Rose, vice president of Purkiss Rose-RSI, a landscape architect and planner for all types of parks (including skate parks) based in Fullerton, Calif. "Their sport is self-paced, and there are no teams or coaches. They kind of have their own uniforms, but this isn't like dealing with an organized sport. If you treat the kids as athletes, not just as kids hanging out, cities and communities can more easily buy into the idea of a skate park. It's just like building a basketball court." Well, maybe not exactly like that. But as with any recreation facility, building a skate park requires a solid game plan. And it probably needs more than a little fund-raising by the end users to get the project off the ground-"something you don't ever see happening with other sports," says Heidi Lemmon, founder and executive director of SPAUSA. In Springfield, Mo., for example, more than 500 kids, parents and other volunteers in early 1997 formed the Springfield Skate Park Association, a nonprofit, grassroots organization that raised $700,000 in cash and in-kind donations to build a 17,500-square-foot indoor skate park from the ground up. For $1 a year, the city agreed to lease a vacant piece of parkland, upon which was constructed a two-story facility that includes 13,000 square feet of skating space (complete with wood ramps, a street course and other obstacles), a 2,500-square-foot balcony for spectating, dancing and other activities, and 2,000 square feet of office and pro-shop space. There is even a skating area for beginners. And already, there's talk of constructing an outdoor concrete park next to the indoor facility to incorporate design elements-such as bowls and snake runs-that couldn't be built inside. The park opened last month, later than originally planned because the local electricians' union that donated $35,000 worth of work fell behind. But better late than never, says Annette Weatherman, president of the association and the person credited with developing the grassroots initiative. "We had to raise the money to build and operate the facility ourselves, which is great," she says. "That put the skate park in our hands." Staffing will consist at any given time of two employees-many of them culled from the association's membership - along with one youth volunteer per hour. Half of the association's board of directors, which oversaw the skate park project, are teenagers (the youngest is 13), and the kids got a say in determining the facility's location, design, name and builder. Weatherman adds that the adults on the board would have vetoed any questionable decisions. "We wouldn't have let a bad vote go," she says. "We would have talked them out of that." As the only indoor skate park in the area, Springfield Skate Park will draw users from more than 100 miles away, Weatherman predicts. "My son is a skateboarder, and we got tired of taking trips to California just so he would have a decent place to skate," she says. Fund-raising and public-awareness campaigns began in late 1996. Weatherman says holding nine skating demonstrations in unusual locations-such as downtown Springfield's pristine and historic public square-and charging skaters $5 to participate drummed up money and local support. Contributions from businesses and individuals also helped. Moreover, the association received blessings from the city's parks director and support from the local media. "That should not be hard," Weatherman says. "Any project involving kids should be great for publicity." Not every project, however, requires its potential users to raise all of the funds necessary to build a skate facility. In the case of Chattanooga, Tenn., the city wound up paying more than it anticipated in order to get the right kind of skate park, which is operated by Sanctuary. "There were certain elements that we thought were really necessary," Rice explains. Chattanooga park and recreation officials allowed Sanctuary to up its price tag for ramps and other elements from about $150,000 to $215,000, Rice says. The facility-including all site work - will weigh in at $700,000 after a pro shop is completed next spring. Sanctuary Skate Park of Chattanooga is a concrete 23,000-square-foot outdoor facility with six light poles, a black plasticcoated fence and an adjacent 20,000- square-foot roller-hockey rink. The 2,000-square-foot pro shop, when completed, will be staffed and offer skating gear and concessions, as well as a lounge area equipped with video games, TVs, VCRs and couches. "I don't know how we would do it if we didn't have our pro shops. Kids practically live there," Rice says. "If you have a facility where kids are being dropped off, you want that child to have someplace to go to the bathroom. And you want someone there who can call 911 if a kid breaks an arm." Sanctuary-operated parks offer users a membership plan, in which skaters and bikers can pay on a six-month or per-session basis. Nonmembers also are allowed to use the facility, but at a premium price. Like most skate parks properly designed and built, both the Springfield and Chattanooga projects relied heavily on several community workshops sponsored by skate park designers. These sessions, which are usually held at least three times during the planning process, introduce community leaders to various design concepts, space configurations, pieces of equipment and price tags. (Be wary of builders and designers who do not have skaters on staff.) Typically, firms will ask a community to develop a task force of 20 to 40 skaters of different ages to sit in on planning sessions and help give them an idea of their needs (based on the community's number of skateboarders compared to the number of in-line skaters) and wants (a street course vs. a freestyle course, for example). Task force members can be recruited by posting flyers around the community requesting input about a proposed skate park. Many builders bring to the workshops three-dimensional drawings or models of parks they've recently designed and use those as a starting point. The goal of the workshops is to gain a consensus about the type of facility to be built. A public meeting then presents the plan to residents, who aren't always sold on the idea. The location of a skate park (which typically calls for a space of at least 6,000 square feet) often is among the toughest issues to settle. "The general public is not fond of the idea that a skate park might be constructed in their neighborhood," Rose says. "While I am successful in dispelling the negative image skaters may have, neighbors for the most part still do not embrace the idea." Perhaps that's due to the perception that skating and illegal drugs go together like wheels and bearings. Lemmon points out that while skaters are prime targets for drug dealers, skate parks can actually serve as a drug-free refuge. "Skate parks work because they keep kids off the streets and off drugs," she says. "By the time these kids are 10, they're tired of skating on their blocks and begin to move around. Kids are then pushed into being renegades because they're running from the cops, who won't let them skate anywhere. The drug dealers move in when these kids are about 13. Their hobbies, besides skating, usually are music and art, and those are the first programs that schools cut. Then the city tells them to find a new hobby because they won't build a skate park." Some communities have waited to ban skating on public property until a proper skate facility has been built. That way, skaters have a place to practice their skills without being arrested-and, yes, they do get arrested. "I got a call the other day from a parent whose son jumped a picnic table in a park-and cleared it!" Lemmon says. "Our attitude is 'Way to go!' But he got arrested, and I want to know what the charge is. Skateboarding is not a crime." Back in Fayetteville, where skateboarding is considered a crime, city officials and a select group of young skaters are proceeding toward construction, aiming to keep skaters from the wrong side of the law. But the $75,000 allocated for the project is not going to be enough, Schuldt says. Plans call for seeking more funds and holding at least two workshops and one public meeting prior to breaking ground. A design firm is already in place, and construction could begin in early 2001, with the skate park opening about a year later, Schuldt says. If his prognosis is correct, Fayetteville will have provided a textbook example of how to plan, design and build a community skate park.