Your architect is from Mars, you're from Venus. To keep you two together, AB presents this self-help dmanual for comprehending the language of design.

Architects all talk the talk-and most of the time you can't make heads or tails of it. It's not their fault. They've got years of training under their collective belt through which they've painstakingly acquired a vocabulary of design that they use every day in their dealings with similarly trained professionals.

Not that it's your fault either. You may only contribute to the planning of one athletic, fitness or recreation facility project in your lifetime. That means that you may suddenly be called upon by members of your staff or people in the community to translate, for example, your architect's love of acronyms. Your ability to differentiate between EIFS (exterior insulation and finishing system) and FF&E (furnishings, fixtures and equipment) is what may make the whole process go more smoothly for everyone. We're not here to blame anyone for this inability to communicate.

We're here to help. To that end, we present the following guide to some of the more confusing aspects of architecture that a layperson might come across during the planning of a new facility. By no means is this list exhaustive; we've bypassed most of the terms with which people tend to be familiar-ceramic tile, glass block, gables-unless we've needed to differentiate them from other similar-sounding terms. We've also limited the categories to three-Architectural Drawings, Structural Elements and Materials/Decorative Elements-and tried to avoid the kinds of technical terms that only the construction manager needs to understand.

Architectural Drawings Two different classes of architectural drawings are used for two different purposes: To allow clients to visualize what a completed building may look like, and to represent technical details for the benefit of clients, architects and construction managers. Visualization of a three-dimensional object (such as a building) in two dimensions is aided by perspective, in which an object is shown in spatial recession. Viewed at eye level from a building's corner, perspective drawings' parallel lines - representing, say, the building's roof line and foundation-will fall away from the viewer toward a single distant vanishing point.

Projections are not viewed in perspective, offering instead a sort of bird's-eye view of a building. An isometric projection is drawn with a 30-60-90 triangle, so the subject is always in proportion; it is therefore a truer representation of its subject than is an axonometric projection. The angle shown in the latter proexcept jection can vary, depending on the needs of the person drawing it. Axonometric projections tend to offer a view from higher up, and thus are especially helpful in showcasing building interiors with the ceiling pulled away-imagine a view of a mouse's maze-allowing rooms to be shown within the context of the entire building plan. More-realistic portrayals of buildings are elevations and renderings.

An elevation is a two-dimensional view of a building's external face, drawn on a vertical plane; typically, four elevations will be used to show the building from each of four compass points. A rendering can be a perspective or elevation drawing, showing building materials, colors, shadows, textures and natural features of the site. CAD drawings (computer-aided design) have quickly become a staple of building design, as they allow the creation and manipulation of two- and three-dimensional representations of a building. A plan drawn from an eye-level view can be "entered" by the viewer, with perspective automatically maintained by the computer as the client performs the "walk-through." Additionally, the point of view can be changed, allowing architects and clients to immediately see how their designs translate into actual future use.

The two most common technical documents are both overhead drawings. The site plan is an aerial view of the entire project site including the facility, parking lots, pedestrian walkways, conceptual landscaping ideas and other site amenities. The floor plan is a drawn-to-scale overhead view of each floor looking down from an imaginary plane cut 3 to 4 feet above the floor. Floor plans show circulation paths and recreational and support spaces, as well as doorways, window openings, furniture and counters. Elements located above the plane of the cut (balconies, overhead cabinets) are usually shown using dashed lines. Ceilings are detailed on a specific drawing type called the reflected ceiling plan, which is a drawing using a similar cut higher up the wall but looking up, not down.

A section is similar to a floor plan proexcept that its imaginary cut is vertical, not horizontal. It is therefore most typically utilized to detail arena bowls and stadium grandstands. A cutaway is similarly diagrammatic, and like an axonometric projection shows the building from an oblique angle. Where it differs is in its representation of both interior and exterior building elements.

Structural Elements A key concept in the construction of sports facilities is span-the horizontal distance between the supports of an upper floor or roof. Building floors and roofs are typically supported by columns and stanchions (upright structural members) or load-bearing walls, and courts for most sports require much larger column-free spaces. This forms the basic concept of long-span spaces (arenas, field houses and ice rinks) that are also referred to as largevolume spaces because of the open height required to accommodate volleyball serves and other sport-specific activities, as well as the construction of vertical-height spectator seating areas. Building walls do not always serve to bear the weight of higher elements, as in post-and-beam construction, in which vertical elements (columns or posts) support horizontal beams or lintels (beams that bridge an opening such as a door or window). In frame construction, the weight is borne by the framework encased within a facing or cladding of light material (as in metal structures). Exterior cladding used as a non-load-bearing wall is sometimes referred to as a curtain wall. Walls sometimes encase columns or parts of columns; those columns are called, as a class, engaged columns. Demi-columns (or half-columns) are half sunk into walls; pilasters project only slightly from walls. A series of regularly spaced columns is called a colonnade.

Stadium decks were once built using a post-and-beam technique, which allowed upper decks to sit close to the field of play but left some paying customers sitting behind posts.

Cantilevers, beams that are supported only at one end by means of downward force behind a fulcrum, eliminate obstructed-view seats but force stadium decks to be stacked farther from the field, in order to provide support for the extended portion of the beam. Cantilevered beams are also used extensively in the construction of staircases and balconies.

The different structural members that make up roofs are not terribly important for laypeople to recognize, but several recur in the sports realm. A truss is a rigid frame composed of a series of triangular metal or wooden members that is often used to support flat roofs over long-span spaces. Trusses also support horizontal members in pitched-roof construction, such as purlins, which in turn support rafters, the sloping members that support the roof covering. Rafters are joined together at the apex of a pitched roof (the ridge). Parapets are low wall projections located at the edge of a building's (if not flat then nearly flat) roofline. This design component can make a building look taller for reasons of maintaining proportion with adjacent structures, or can be used to screen items such as roof vents and exhaust hoods projecting above the roof.

Flat or sloping roofs sometimes employ eaves, an overhanging portion, to keep rain from running down exterior walls. (Coping is a similar component with a similar purpose, although the term is used liberally to represent a variety of treatments that cover the top of a wall.) Fascia refers to the horizontal band that joins the roof to the eave (in home construction, the gutters are affixed to the fascia). Eaves are sometimes referred to as the soffit, but this is a term that has many applications. The soffit is the underside of any architectural element, including balcony overhangs and staircases. In its original and most correct meaning, soffit refers to the inner curve of an arch, which is a curved means of spanning an opening, used in place of a lintel.

An arched ceiling is called a vault, of which there are many types in architecture but few that find their way into sports facilities. One exception is in the form of barrel- or halfvault skylights that grace a number of building spines - that is, the backbone of a building's floor plan, most often the main circulation pathway in an arena or recreation center.

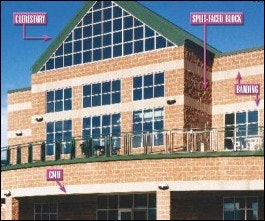

Skylights, whether flat, pyramidal or taking other shapes, are distinguished from clerestories by being set into ceilings or roofs. Clerestories, which occasionally will be seen spelled "clearstories," are traditionally walls containing windows that are set vertically above a low roofline and topped with the uppermost rooftop, as in a church gallery. Windows as a class will sometimes be described as fenestration, which literally refers to openings, whether used to describe buildings or the human body. In the realm of architecture, it refers to the arrangement, proportioning and design of all openings, including windows, doors and skylights.

The underside of a roof (or for that matter, floors) is called, of course, a ceiling. These large surface areas are irresistible to many architects, who might use splines-thin wood or metal strips - to visually break up the ceiling into different surface patterns. Coffered ceilings utilize sunken square or polygonal ornamental panels to the same effect; caisson and lacunar are two lesser-used terms for coffering. False ceilings-that is, ceilings that are suspended below the structural ceiling-are known as suspended ceilings. The enclosed space between the two that often acts as a return air duct to an HVAC system is called a ceiling plenum.

Other types of roof structures common to the athletics market dispatch with these sorts of details altogether. Tensile or membrane structures are flexible building systems made of thin coated fabrics supported by a series of masts and stabilized by cables. These systems are often used as roofs over stadium spectator areas and as domes over stadiums and arenas, particularly those in temperate climates where snow loads are not an issue. Inflatable structures, a class of tensile structures, are supported by the difference in pressure between the air inside and the air outside. Air is pumped in using fans, with air escape prevented by the use of airlocks at entrances. Inflatable structures enjoy applications from big-league stadiums to practice football fields to tennis courts, both temporary and permanent.

Materials/Decorative Elements The most common job-site material is undoubtedly concrete, which in slightly varied forms is utilized for foundations, structural beams, floors, walls, sidewalks, parking areas and a host of other uses. The stones in concrete are what set it apart from mortar, which shares concrete's base of cement (or lime), sand and water. Mortar, or grout, is used to bind bricks and concrete blocks together, to fill interior spaces of concrete-block walls and, in some forms, as a surface coating-for example, stucco, a plaster made of gypsum (hydrous calcium sulfate, the primary ingredient in wallboard), sand, water and slaked lime. Cement mortar is also a key ingredient of terrazzo, a flooring surface consisting of marble chips mixed with mortar, which after hardening is ground and polished. Different varieties of concrete and mortar find their way into a number of areas in sports facilities, including tennis courts, tracks and pools. A commonly confused pair of materials are gunite and shotcrete. Gunite is a popular swimming- pool shell material consisting of cement, sand and water-mortar, in other words-that is sprayed onto a mold. Shotcrete uses the same application technique and ingredients (plus stones); it is used to make pool shells and the interior shells of domes.

Structurally, concrete is notable for its high compression capability and for its poor tension characteristics. (It will hold its form under huge amounts of weight but, when subjected to longitudinal stresses, will break apart rather easily.) Reinforced concrete adds steel reinforcing bars (known in the trade as rebar) to give a concrete slab or beam the ability to withstand tensile stresses. The rebar in reinforced concrete can be put into tension in the factory (prestressed or pretensioned concrete) or on-site (post-tensioned concrete).

Reinforced concrete can also be fabricated off-site (precast concrete) or produced on-site (cast-in-place concrete); the cost of the throwaway forms involved make up nearly half the cost of the latter. Precast wall sections some times are referred to as tilt-up panels, as they are prefabricated and then tilted up and assembled on-site. The lower cost of fabricating forms for precast concrete (made of metal, they can be used again and again) allows precast concrete to be used in the production of lower-cost accent pieces, often taking the place of limestone or granite in lintels, cornerstones, keystones and so on.

Masonry, which refers to work with brick or stone, offers many aesthetic options, both in the variety of colors and textures of natural materials and in the different ways these materials are cut. Ashlar masonry, for example, consists of hewn blocks of stone, wrought to even faces and square edges, and laid in horizontal courses (tiers) with vertical joints (the mortar between). Stones left in their quarry state and not made even and square are called quarry-faced masonry. Masonry utilizing blocks having irregularly shaped faces is called polygonal masonry. A technique known as rustication, used to lend more texture to exterior surfaces, involves the use of large blocks separated by deep joints of mortar. In banded rustication, only the horizontal joints are emphasized; smooth or chamfered rustication features blocks with smooth faces separated by beveled joints (in the shape of a V). Concrete block, which is often referred to as CMU, or concrete masonry units, can similarly be worked to different textures.

The most common types are split-faced concrete block (or masonry), in which a block is hewn and used bearing whatever ridges are left in the material from the cutting process; and ground-faced concrete block (or masonry), in which the cut pieces are ground to lend the surface a heavily but more evenly textured appearance.

The natural color variety of bricks, which are made of fired or sunbaked clay, allow architects to make aesthetic statements by selecting a certain color or by specifying more than one color and setting them in various patterns, sometimes interspersed with concrete blocks and stones. Banding involves running one or several continuous horizontal courses of a contrastive color of masonry (sometimes known as belt courses). This can be done simply to add visual interest, but banding can also be used to help break up a building's apparent scale. Structurally, brick can be used as a loadbearing material, but more often is specified as brick veneer, which is essentially sliced brick pieces affixed with mortar to a concrete load-bearing wall. This type of brick is also known as face brick or finish brick.

Masonry is also in wide use in building interiors and, inside, can be used in ways similar to these. Another common interior material, tile, is well understood by the professional and layperson alike, although confusion may possibly exist when differentiating between ceramic tile (glazed fired clay), quarry tile (unglazed semivitreous tile extruded from shale or natural clay) and composite tile (vinyl).

"Composite" is a term that may also crop up in discussions of roof systems, composite shingles being of the type used in most home construction. (Clay tiles are also used in the Spanish Mission style of architecture.) While the choice of materials for roof systems tends to fall outside the scope of aesthetic considerations, the standing-seam metal roof is one notable exception. In this application, sheets of metal of equal widths are laid from the ridge of the roof toward the fascia, with the edges pinched up and seamed perpendicular to the roof surface.

Say What? While this guide could not possibly touch on an architect's full vocabulary, it should help you and your architect communicate more successfully. If you continue to be bewildered in conversations with your architect, don't hesitate to ask for clarification. Architects and clients may not always speak the same language, but a little bit of patience and understanding-by both parties-is sometimes all that's needed.