Athletics is a competitive business. Professional, collegiate and youth athletics programs constantly seek a competitive edge. For today's programs, sports performance centers have become the new arrow in their quivers. Successful sports performance programs do two basic things: acquire information and implement that information in a consistent, logical and beneficial way.

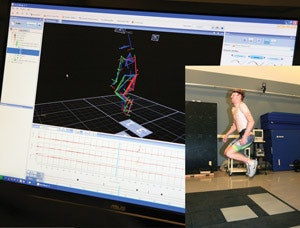

INFORMATION IS POWER Athletic trainers at Colorado Mesa University's Maverick Center use motion-capture software to evaluate a student-athlete's movement. - Click to enlarge

INFORMATION IS POWER Athletic trainers at Colorado Mesa University's Maverick Center use motion-capture software to evaluate a student-athlete's movement. - Click to enlarge

Information, in this case, is primarily data or analysis specific to an athlete's performance as it relates to physiology and psychology. Most performance facilities are primarily used to acquire information. Whereas athletes may lift weights four to six times a week, they may only utilize the performance facility three or four times in a season. A typical pattern might be to use the performance facility to establish some benchmarks at the beginning of a season, tailor the training program to focus on weaknesses, and test again several weeks later to measure improvement.

A classic example is a rower, who must be both aerobically and anaerobically fit. But how does a coach know if the training should focus more on arms and legs or heart and lungs? A VO2 max test can provide the answer by measuring how efficiently oxygen is used by the rower's muscles. It may be that the athlete is not able to use the full capacity of his or her arms and legs because the heart and lungs can't keep up. The training regimen would be modified to add more running and less lifting to ultimately go faster on the water.

Colorado Mesa University Maverick Center - Click here to see more

Colorado Mesa University Maverick Center - Click here to see more

A VO2 max text is particularly useful for rowers, but what about other sports? The diversity of programs used to track athletes' metrics can be overwhelming when initially planning the design and programming of a performance facility. Which athletes need testing? What kinds of programs does each athlete need? How does the information acquired in testing get implemented? What is the right balance of psychology and physiology? In a world of limited resources, the questions quickly pile up.

In the design of sports performance facilities, the most critical element is the definition of the programs and testing methods to be utilized, as space and technologies to support each program will rapidly translate to significant costs. The range of potential programs and services is broad. Basic categories include:

Sports Physiology — Uses tools such as force plates, high-speed motion capture, lactate TH testing, and VO2 max testing to evaluate and improve technique and training regimens.

Sports Psychology — Uses traditional psychotherapy techniques such as visualization, relaxation and self-talk to manage stress and enhance athletic performance.

Psychophysiology — Uses neurofeedback, biofeedback and computer sensory training to develop increased control of the body and brain.

Nutrition — Integral to all aspects of athletic training and performance, including proper hydration, maintaining glycogen levels during training and competition, recovery and building specialized body types for specialized activities like weight lifting or distance running.

Anthropometry — Uses tools to precisely measure physical characteristics of the human body such as proportion, height, weight and body-fat percentage. Along with resting metabolic rate, it is often used to inform diet.

Computer Simulation — Competition situations are experienced virtually to train the mind and body for quick analysis, quick reaction time and good decision-making.

Recovery — A complete and rapid recovery after strenuous exertion allows athletes to return to full training or competition performance faster. Techniques to improve recovery include cold therapy, warm therapy, massage, and swelling-reduction aids such as compression garments.

Concussion Analysis — Although a very important topic that deserves attention, there is surprisingly little consensus about what a concussion is, the best way to diagnose one and how to recover from one. Several studies have addressed this topic in recent years, and many in the coming years will change the way brain injuries are addressed.

High-Altitude Training — This sealed space gives the ability to control oxygen, temperature and humidity to allow athletes to train harder in high-oxygen environments or to stimulate the production of red blood cells in low-oxygen environments. The ability to control temperature and humidity allows pre-training for events away from the training site and allows nutritionists and physiologists to gather metrics like sweat loss for tailored regimens such as hydration.

Rehabilitation — The tools and resources of a performance lab can be used to help bridge the gap between medical rehabilitation and full potential performance. For instance, if an athlete is believed to be 95 percent recovered from knee surgery, a vertical jump from a force plate can determine exactly how much force is being put on each leg.

Each program component requires a tailored space, specialized equipment and technologies, staff to conduct and interpret the testing, and consultation with the athlete and/or coach to initiate a new training regimen. The challenge is determining the most beneficial knowledge base for the athletes being served and then translating space and equipment needs into a thoughtful and cost-effective design.

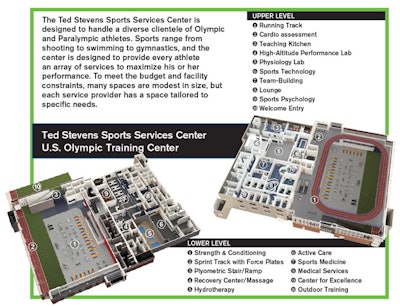

Click to enlarge

Click to enlarge

For instance, at the U.S. Olympic Training Center in Colorado Springs, Colo., the design of the new sports performance center emphasized the full range of programming — a direct reflection of the wide range of sports and athletes that use the center to focus on improved performance. Colleges and universities face similar diversities, while a professional sports team may be able to focus specifically on particular analyses and training regimens.

The size and nature of the programs will also directly influence the amount of space needed. Collegiate facilities may serve a large number of athletes whose visits are spread throughout the day but may require a smaller footprint than a professional facility built to serve all of its athletes during a very short period of time.

RELATED:

Tracking Technology Revolutionizes Athlete Training

Incorporating Athletic Performance Training Aids into a Conditioning Program

Are Performance-Enhancement Centers the Next Big Thing for Young Athletes?

How the facility will interact with and enhance existing programs or departments is another design factor. For stand-alone, fee-for-service facilities, fitting into existing programs is less important, but on a college campus, athletes are supported by coaches, strength and conditioning coaches, and athletic trainers. A performance facility needs to serve all three, but not wholly any one. To develop the best design, the athletic director should work jointly with coaches, trainers and architects to make key decisions regarding services, the nature of the spaces and the center's location relative to other facilities.

Western State Colorado University High Altitude Performance Lab - Click here to see more

Western State Colorado University High Altitude Performance Lab - Click here to see more

Interestingly, though, a sports performance center does not need to be located directly adjacent to these other uses, or locker rooms for that matter. A strong parallel can be drawn between a sports performance center and a medical clinic. Athletes and coaches will seek these services when needed — they are typically not a component of an athlete's daily training regimen.

Developing a culture of shared expectations and benefits should be central to the determination of where a facility is located. Its ease of accessibility may be essential to its return on investment, and most important, its benefit to the athletes it serves. Simultaneously, it is also important to consider confidentiality as an essential element of a successful program, particularly if the center serves outside community members.

A performance facility is often more of a program than a defined space or place. Testing in the lab may be the most convenient in many cases, but its size and location may be limiting. Track programs, for example, may benefit more from force plates at the track where there is adequate space for running and jumping than building a similarly large space just for force plates inside a performance facility. Similarly, portable motion-capture technology can be deployed to basketball courts, pole vault pits and ski slopes much easier than these situations can be simulated in the lab. For programs that operate at multiple sites, adequate secure storage that can be easily accessed by vehicles becomes essential. Ideally, the storage space can be combined with an equipment-repair function.

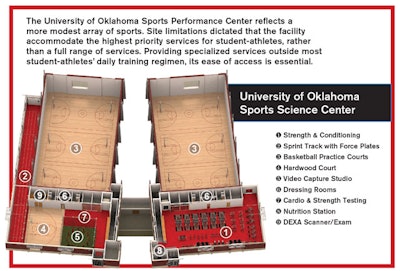

Click to enlarge

Click to enlarge

Success of a performance center is driven not just by the programs offered but how they are presented. In combination with colors, textures and natural materials, the introduction of daylight through windows or clerestories can often make laboratory spaces more inviting and comfortable for athletes and staff alike. Comfortable social zones in waiting and recovery areas can also add to the experience, counteracting the clinical environment within. Similarly, group activities, such as nutrition classes or team-building exercises will benefit from comfortable, acoustically isolated and technologically flexible spaces with adequate storage.

As with any thoughtful planning process, it is important to think beyond today's needs. The sports sciences will continue to evolve, and sports performance facilities must be built to evolve, as well. Open structural systems with ample ceiling heights; partition walls that can be easily moved or eliminated; mechanical, plumbing and electrical systems that have additional capacity to take on future uses; and an adaptable technology backbone are essential elements of future flexibility. Identifying how a building can expand in the future should be an early and repeated question throughout the design process. With forethought and creativity, a new sports performance facility can be built to perform as well as the athletes it serves.

Andy Barnard, AIA, is president and principal of Denver-based Sink Combs Dethlefs. Ernest Joyner, AIA, is an SCD principal specializing in sports and recreation design.

This article originally appeared in the September 2015 issue of Athletic Business with the title "Performance Standards"