Inspired by the popularity of a makeshift climbing gym, Oregon State University took racquetball court conversion to another level.

In 1990, three years after racquetball's popularity had hit an all-time high nationwide, climbing enthusiasts in Corvallis, Ore., volunteered to remodel two racquetball courts located under the stands at Oregon State University's Parker (now Reser) Stadium. Having seen the writing on the wall, they covered it with plywood and handholds.

Indoor climbing was on the ascent, and what better place to build a gym to meet local demand than in a space beneath football seating left dormant by racquetball? The OSU department of recreational sports helped fund the purchase of holds and took over the site's operational control from the athletic department. Synthetic turf salvaged from a nearby field house lent some give to the hardwood court flooring underneath. It was a cherished, if crude, clubhouse for a growing climbing community. "It would get very busy," says the recreation department's associate director of facilities, Bill Callender, "and people really loved it."

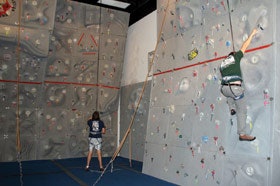

A lot has changed since then. Witness the state-of-the-art climbing gym built as part of a 2004 renovation of OSU's Dixon Recreation Center, where a ground-level racquetball court was converted into a bouldering cave that emerges from underneath a second-floor court (left intact) and wraps upward along that court's exterior wall to form multiple belayed courses measuring 42 feet high. Rendered obsolete, the stadium climbing gym has seen yet another conversion - to a field-maintenance storage room.

Across the country, fitness facilities - particularly the decades-old variety often designed with 10 or more racquetball courts - are putting a percentage of those increasingly underutilized spaces to more productive use. Racquetball as an offering hasn't been completely abandoned; OSU's 33-year-old Dixon Center maintains seven of its original 10 courts, two having been sacrificed for lounge and circulation spaces at the time of the bouldering cave conversion. But the most recent statistics compiled by the Sporting Goods Manufacturers Association reveal that racquetball now attracts roughly a third of the participants it once did, and indeed has been surpassed in popularity by both indoor climbing and martial arts. "There are people who play," says Dennis Fagan, regional sales manager at Montgomeryville, Pa.-based Vertispace, which manufactures platform systems that convert racquetball courts into separate, stacked rooms totaling 1,600 square feet suitable for alternative fitness use. "But it's hard for a facility to devote 800 square feet to two people at a time."

The University of Alabama recreation department now packs up to 22 exercisers into one 20-by-40-foot former racquetball court during any of the three to four group cycling sessions it schedules every weekday, each one so popular that turning aspiring riders away has become commonplace.

"Trend-wise, we saw what other campus rec facilities have seen," says George Brown, executive director of university recreation on the Tuscaloosa campus, where the Student Recreation Center was built with 14 racquetball courts in 1982. "At that time, racquetball play was at a zenith compared to what we're seeing today."

Two major building renovations have taken place in the interim, as has a shift in user preferences. The most recent work, a $24 million renovation launched in 2004, ultimately saw two racquetball courts combined as one climbing gym, another turned into a combative arts room and a fourth the group cycling studio. "We saw a lot more use with group exercise, and in particular group cycling programs," says Brown, who teaches a one-credit class in the studio. "Before the conversion, we had a studio for our bikes, but it didn't have any of the sights, sounds and overall dynamics of a studio dedicated to that kind of exercise."

Enter a creative team of graduate art students, who built their master's theses around the renovation of a racquetball court. "We bought the materials, but they drew the design and actually constructed the studio over a three-month period," Brown says. "They retrofitted it, dropped the ceiling, put in fans, put in acoustical tiles, changed out the walls with some fluorescent tube lighting to give it some mood effect - all within a budget of no more than $20,000, and they did all the labor."

The purchase of 22 new stationary bikes added another $20,000 to the retrofit. But on the conversion cost scale, group cycling studios likely fall somewhere between combative arts rooms (which require little more than floor mats and wall padding) and climbing gyms. To be sure, modest climbing conversions involving handhold-on-plywood panels affixed to existing structural walls can be accomplished for a few thousand dollars. But those that feature a simulated rock face, complete with overhangs and their requisite internal steel support structures, can easily reach the six-figure strata - particularly if additional steel studding is required within the court space in the event it lacks walls constructed of block, tilt-up or poured-in-place concrete to which the climbing hardware can be bolted directly.

As would-be climbing gyms, racquetball courts present additional conversion pros and cons. "The nice thing about a racquetball court is it is very easy to close the door and secure it if it's not in use," says Scott Hornick, director of sales and marketing for Barre, Mass.-based climbing wall manufacturer Rockwerx. But that same door can present problems during the conversion itself. Racquetball courts are typically arranged side by side along a hallway, and negotiating tight corners with large sections of climbing wall can be difficult, if not impossible. Either the climbing wall has to be cut into manageable pieces or the overall spatial design has to include removal of one or more court walls.

Claustrophobia is a concern worth addressing from the beginning. Most racquetball court walls stand a mere 20 feet - high enough to require a belay line, but not particularly challenging to adult users. A temptation may be to overcompensate. "Everybody wants to fill all the walls," says Adam Koberna, vice president of sales and marketing for Bend, Ore.-based climbing wall manufacturer Entre Prises USA. "You just don't want to do that. It's one of those things that if you do it, you're creating a cave."

Leaving all four walls alone and centering a climbing tower within the space is another option, though one that's not without its own potential perils. For starters, portions of wood flooring will have to be removed to secure the tower superstructure to the subfloor. And then there's the space issue. "When you deal with a climbing wall, you deal with swing cones - basically how far do people swing away from the wall and what are they going to hit when they swing out? When you create a tower and you put it in a space that's only 20 feet wide, you do not create a lot of room for people to swing around on two sides," Koberna says. "That becomes detrimental to the design. You're putting a lot of money into a little space, whereas you could spend less money for a lot more effective climbing."

Adding to the sense of closeness in a converted racquetball court is the potential lack of adequate air handling. Oftentimes, individual racquetball courts will have their own air-handling systems. "Because they were sized for a maximum of four people, you're going to have to address in the retrofit how you are going to accommodate, in our case, as many as five times that," says Alabama's Brown. "In the climbing wall situation, it wasn't a big problem, because we took two courts, we put a glass exterior on it and we gave it the proper due diligence in terms of HVAC and flow. With the group cycling studio, we had to think long and hard about how to bring in and circulate more air."

"Altering the HVAC to deal with more people and the chalk dust associated with climbing walls is always recommended," Koberna adds. "But the main reason we would alter the HVAC would be to accommodate the steel substructure of a climbing wall. We can design around existing HVAC, but it can limit the final programming of the wall."

Direct supervision, a moot point in a traditional racquetball setting, is another conversion design consideration - particularly when it comes to climbing. Hornick says bouldering walls, with a typical maximum height of 12 feet, not only make for a good fit within the spatial limitations of a racquetball court, they don't require much handholding on the part of facility staff. "You can design the space so that it's not supervised. If you stick with bouldering, you can have something that could be open all the time for walk-up usage," he says. "But once you start to get up to 20 feet, and you get a novice in there who doesn't know how to put a harness on or how to clip into the line, then you really need to have at least one person in there facilitating and supervising."

Might racquetball bounce back? And could a court conversion be reversed to again capitalize on the sport that once represented a cornerstone of fitness center programming? SGMA figures, at least, don't foretell a bright future. Though racquetball participation ranged between 4.1 million and 4.7 million people between 2000 and 2005, it dipped below 3.5 million by 2006, the most recent year for which statistics are available.

If walls, floors and ceilings remain unaltered, one can always remove stationary bikes or Tae Kwon Do mats from a racquetball court and return it to its original purpose. But for a facility opting for a climbing gym, there's usually no turning back. Same goes for a split-level fitness studio conversion using a platform, as column footings require cutting through a court's hardwood floor to reach the slab underneath it. Yet, despite this apparent permanence, a platform is "considered a piece of equipment by the IRS," says Vertispace's Fagan. "A lot of health clubs will lease it, just like a lot of their other equipment."

Oregon State's Callender, for one, likes the view from 42 feet. "Our climbing wall is so popular, we're at capacity," he says, adding that the Dixon Center conversion, which is open to students between four and six hours a day when not rented out to special groups or occupied with academic classes, can handle 35 individuals at a time. "We've already got a conceptual plan completed by an architect to put up a wall in the field house. It will handle instruction and special programming, leaving our space more for recreational use."

At Alabama, university recreation officials aren't about to put the brakes on their group cycling conversion. In fact, Brown envisions future enhancements. "We already have a state-of-the-art Bose sound system in there," he says, "but I think the idea now is that behind the instructor there might be some visualization of mountains, valleys, desert land - something that gives the students further stimulation."

Those stimulated by the ricochets of a blue ball are still served by nine courts, which Brown considers just about right to meet current racquetball interest levels. But that could change as UA's enrollment speeds toward 30,000 students. Calls for another conversion can already be heard. "We've sort of created another problem," Brown says. "There's such demand that some people are saying that we need to do this to another racquetball court."