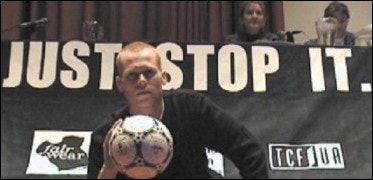

A Former Soccer Coach Brings to Campus Stories of Nike's Workforce in Indonesia

"How are you doing?" said Jim Keady, introducing himself to Phil Knight, the CEO of Nike Inc., as Knight was having lunch with a friend March 7 at the shoe-and-apparel company's Beaverton, Ore., headquarters. "Nice to meet you finally."

"Hi, good to see you," Knight replied.

Within minutes, as Keady, a former professional soccer player and college coach, explained that he had come all the way from New Jersey to voice his concern to Knight about Nike's workforce in Indonesia, the once-cordial exchange turned testy. "Well, I am not talking to you," Knight said.

"I've gotten stonewalled at every turn," Keady persisted. "The workers had asked that we bring you back to Indonesia to meet with them in their homes."

"Do you understand no?" Knight shot back. "You just got a no. I am not going to talk to you about it."

Thus ended the first and only dialogue to date between Keady and Knight. Though brief, it served to punctuate an exhausting cross-country speaking tour for Keady, 29, cofounder of separate initiatives - the Olympic Living Wage Project and Nike Shareholders for Justice - intent on leveraging change in Nike's labor practices. Since questioning the morality of a shoe-and-apparel contract struck between Nike and St. John's University in 1998, the one-time assistant coach for the Red Storm men's soccer team has assumed a national leadership role in the now-five-year-old campus anti-sweatshop movement. His insubordination at St. John's, which amounted to a refusal to wear the soccer team's standard-issue Nike gear, cost Keady his coaching job, or so he claims in a lawsuit against the university and Nike (oral arguments before a judge were scheduled to begin June 20). Undeterred, the then 27-year-old graduate student earned his master's degree from St. John's, spent a month interviewing Nike workers in Indonesia and another eight months retelling their stories to students at some 65 different college campuses. Whether speaking for his requested $1,000 honorarium or for nothing, Keady's message remains the same: While Nike rakes in billions of dollars annually, its workers in Indonesia are not justly compensated.

"It's about redemption," he says. "It's about looking at a situation of injustice and the people who are the exploiters to try to redeem them through the power of love. That's our ultimate goal, to redeem people like Phil Knight, Michael Jordan, Wayne Gretzky, Mia Hamm, Tiger Woods and, in a sense, all Nike shareholders. The same kind of love that we show for the workers, we have for them, but the workers need justice."

There was a time not long ago when Keady wore Nike products. In fact, a fellow coach at St. John's once took him to task for wearing a Nike shirt during a preseason soccer tour of Europe (St. John's at the time was strictly an Umbro school). But not long after that, a professor instructed Keady to write a research paper linking moral theology and sports, an assignment that would steer Keady into the epicenter of the anti-sweatshop debate. Based on published articles he had read on the labor practices of Nike, Keady advised university athletic officials against a pending $3.5 million shoe-and-apparel deal with the company. He was promptly told to keep quiet, but by then the controversy had hit the front page of the student newspaper. Ultimately, Keady says, he was forced to relinquish his position on the coaching staff.

His attention then turned to Nike. Keady offered more than once to work for the company in Indonesia, but was rebuffed each time. Instead, he spent a month in Tangerang, living on Nike's highest worker wage - the American equivalent of about $1.25 per day. Through an interpreter, he gained the trust of Nike employees there, often interviewing groups of 20 workers at a time. Keady says this "marginalized, minimally educated population" had been sold on "working in an air-conditioned building for a really successful American company."

"The Indonesian people are just mad for soccer," he adds, "and Nike would say things like, 'You might make Ronaldo's shoes.' They bought it hook, line and sinker." Then Keady would tell them that some Americans hold the impression that the workers have been given great jobs. "Every reaction was strong," he says. "It was either laughter or they would just shake their head."

Promising to pass on what he had learned in Tangerang to whomever would listen in the United States, Keady embarked on his speaking tour, and he found strong reaction here, as well. At St. Olaf College in Minnesota, for example, nearly a quarter of the student body witnessed Keady's interactive multimedia presentation, which includes video footage and a slideshow set to music. The University of Notre Dame invited Keady to speak four separate times, and some schools have asked him to return this fall. "It's taking all of this academic research that's been done, which is fantastic, and humanizing it," he says. "That's what we think has really helped to galvanize people, telling these human stories."

The worst of these, according to Keady, tell a tale of verbal and physical intimidation of workers, even threats made at gunpoint. "Most of the workers we talked to said they're hungry every day," Keady adds. "They have headaches, both from the glues and the other chemicals that are in the factory, and from not eating properly. Their health is not good."

Not surprisingly, Nike officials tell a different version of the story. Failing to take advantage of offers for a phone interview during which specific questions could be answered, Vada Manager, Nike's director of global issues management, said in an E-mail message that Keady "is really garnering publicity for his lawsuit against Nike and St. John's University." He goes on to write, "Nike doesn't operate or condone sweatshops. We have said that we have progress to make in Indonesia. However, the information in [Keady's] traveling presentation isn't an accurate portrayal of factory life, either."

Manager chose a more cavalier tone when discussing the overall anti-sweatshop movement in the March 12 issue of Newsweek: "Nike approaches this as it approaches everything - as competition. And we aim to win."

It's that very attitude that Keady predicts will be Nike's downfall. If the company really wanted to improve worker conditions in Indonesia and elsewhere, it has the resources to do so virtually overnight, he says. So why hasn't it? "Number one, it goes against the logic of capitalist economics. The goal is to maximize profit regardless of the cost to humanity or nature," says Keady, who has invested roughly $30,000 of his own money into his anti-sweatshop projects. "Another factor at work, particularly at Nike, is that they're sportspeople. Phil Knight's a competitor. He's a runner. It's this almost bratty bravado that's saying, 'I built this myself. You're not going to take it apart.' No, you didn't build it yourself. You have half a million people globally who are making your products every day. You don't get rich independently of other people. There is a social mortgage to all wealth that's generated."

Nike stock, in fact, has underperformed this year, and while Wall Street analysts attribute that to an overall weakening of the U.S. footwear market, Keady prefers to see it as reaction to Nike's admission Feb. 21 to facilitating worker exploitation. Not that Keady wishes financial ruin for Nike; he bought five shares in the company Feb. 28 to launch his Nike Shareholders for Justice campaign, through which he plans to present his research at shareholder meetings. "If the leadership on these issues isn't going to come from Phil Knight, we're going to change the company from the bottom up," he says.

How close is he to doing just that? Keady subscribes to a theory applied to social movements that speaks of a "tipping point," where support builds steadily like the ascent of a roller coaster to a point where sheer momentum takes over and change becomes inevitable. "I think we're near that tipping point, and things are going to happen," says Keady, who plans to meet with more factory workers before year's end during a trip to Nike manufacturing locations in Mexico. "If we can get things sorted out in Indonesia, that's great, but that's only one-fifth of Nike's global workforce. We've got another 450,000 people who we've got to help out. And after we create a model that works for Nike, adidas is next, then Reebok, then all the other ones. That's the level of commitment I have to this, and I think it's a level of commitment that's necessary."