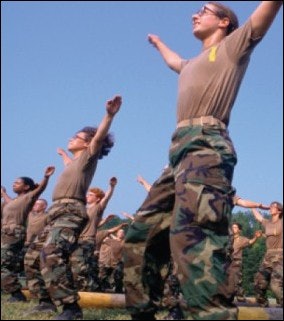

Fitness has always been a priority in the military, but new initiatives are ensuring that America's Armed Forces are fitter and healthier than ever

Up until Sept. 11, 2001, most United States Navy recruits could expect to spend at least a year, maybe even closer to two, on dry land before being called to serve on the seas. But that fateful day changed many things about the way the American military operates - including not only its deployment schedule, but also how its highest-ranking officials view fitness.

While physical preparedness is inherent in the definition of military readiness, all branches of the U.S. Armed Forces - the Air Force, Army, Coast Guard, Marine Corps and Navy - are realizing that fitness is now even more important.

"The global war on terror is as resource-intensive as any war that preceded it, and our most valuable resources are human resources," says Lt. Col. Brian McGuire, program manager of the U.S. Marine Corps' new Sports Medicine Injury Prevention Program (SMIPP), a pilot effort that involves certified athletic trainers (ATCs) working alongside and advising officers in charge of training new recruits to help reduce musculoskeletal injuries and lost training days. "We're now trying to apply what works for civilians to military personnel. Think about this from an athletic department perspective: If there was no training room, all of the athletes would have to go to the student health center or the hospital for care, to get an ankle taped, to get a hamstring stretched and so on. People in the athletic department just wouldn't put up with that. What we've done is complement the services that are already available on the treatment side, along with providing commanders with injury-prevention expertise to help them develop their programs. The Marine Corps is still a volunteer service, and we need to do what we can to mitigate risk and keep everybody in the game."

Each branch of the U.S. Armed Forces is attempting, in its own way, to keep all of its service members in the game. The Air Force, for example, is in the midst of its massive "Fit to Fight" campaign, which includes improving the fitness levels of airmen and airwomen, as well as either renovating existing fitness centers or constructing new ones on bases all over the world. The Coast Guard, meanwhile, has simply refined some of its health and fitness policies regarding weight control and physical training. Then there's the wide-reaching "Get Moving Navy" initiative, which aims to increase physical activity and improve nutrition and lifestyle habits among all sailors and their families, as well as retirees and civilian employees.

Diana Settles, manager of the Navy's injury prevention and physical fitness programs and one of the driving forces behind "Get Moving Navy," likes to show visitors photos illustrating how participation in exercise and sports directly corresponds to operational activities in military training and deployment settings. For example, playing flag football mimics the agile movements ground troops must make when running with an object on rough terrain or dodging enemy fire, performing heavily weighted arm curls requires the same motions involved in loading missiles for launching, and lifting free weights is similar to carrying wounded comrades to safety. "The military is like athletics," she says. "We use the same agility and coordination, muscular fitness, aerobic fitness and flexibility that are used in many sports."

Here's a branch-by-branch look at some of the recently launched initiatives that take aim at increasing fitness levels and reducing injuries.

U.S. Air Force

In July 2003, Air Force Chief of Staff General John Jumper announced his "Fit to Fight" initiative, which outlined a new system of fitness testing in which each of the Air Force's nearly 600,000 men and women in active duty and the reserves are evaluated annually, effective Jan. 1, 2004, in four major components: crunches, push-ups, an abdominal circumference measurement and a 1.5-mile timed run. The component scores are added together for a composite fitness score that determines whether a person falls into the "excellent," "good," "marginal" or "poor" categories. (See " 'Fit to Fight' Takes Off," Jan. 2004, p. 9.)

"He wanted to make the operational fitness requirements more demanding and consistent with the fitness requirements airmen experienced in basic training, the Air Force Academy, ROTC or Officer Training School," says Margaret Treland, manager of the Air Force Fitness Program.

But Jumper stresses that "Fit to Fight," which combined the Air Force's fitness and weight management programs, is about more than simply passing an annual fitness test. "We are changing the culture of the Air Force," he wrote in a message to all Air Force personnel last year. "This is about our preparedness to deploy and fight. It's about warriors. It is about instilling an expectation that makes fitness a daily standard, an essential part of your service."

Air Force commanders are mandated to provide up to 90 minutes of duty time a day, three to five days a week, for physical training - which can be done both in units and individually. Previously, Air Force personnel were responsible for maintaining their own level of physical fitness, often during their own time, to meet mission readiness.

Each Air Force unit now has a specific number of physical training leaders assigned to it. As fit, active-duty personnel who have a desire to share their healthy lifestyle with their peers, PTLs are assigned by their commanders to lead and assess "Fit to Fight" programs. They must undergo an eight-hour training course, administered by the Health Promotion Operations Department of the Office of the Surgeon General of the Air Force, which teaches them how to look for signs of fatigue, emphasizes the importance of hydration during exercise and explains proper techniques that help avoid injuries.

As a result of "Fit to Fight," Treland reports that fitness centers located on Air Force bases worldwide have experienced a significant increase in daily visits. And Air Force commanders are in the process of developing plans to build new or renovate existing fitness centers to meet the increased demand generated by the program. Seventeen facilities have been renovated or newly constructed since 2000, with a half-dozen more projects slated for completion by December, Treland says. Several others are in various stages of design and construction, which is expected to continue until at least 2011.

U.S. Army

This summer, the Army kicked off a new effort aimed at increasing the level of training for employees working at on-base fitness centers. "We're trying to give people more hands-on education and help them feel like they really understand what they're learning," says Janet MacKinnon, the Army's fitness program manager, stressing that the training targets facility employees who oversee customer service, equipment orientation and other non-managerial duties. "We're taking them beyond the basics. We want to concentrate on addressing staff members within a facility and determine what competencies they have, because there is a direct correlation between those competencies and how soldiers train."

By the end of this month, fitness-center personnel on at least five Army bases - Fort Bragg, N.C.; Fort Campbell, Ky.; Fort Carson, Colo.; Fort Eustis, Va.; and Fort Lewis, Wash. - will have undergone up to four days of training to, among other things, increase their knowledge of the body's various muscle groups and how they interact with each other, as well as develop a better understanding of what pieces of equipment best complement specific workouts and fitness needs.

Training may continue at facilities overseas later this year, and at other bases in the United States and worldwide next year, MacKinnon says. Such education is crucial now more than ever, she adds, because plans for Army fitness programs don't include hiring more staff.

That said, since 2001, the Army has been planning to build new fitness centers to replace antiquated facilities - many that are more than a half-century old and include only small spaces for weight equipment and even less room allocated to cardiovascular fitness machines. "We need more space for programs that people need," MacKinnon says.

But when the Army's 480,000 soldiers are deployed, working out under any condition becomes a challenge - and sometimes even a hazard. That's why the Army recently developed the Morale, Welfare and Recreation Deployed Fitness Guide for all soldiers in the field. Each laminated, spiral-bound guide, which fits into the pockets of the Army's standard-issue uniform pants, also comes with approximately six feet of 3 / 4 -inch resistance tubing. "When soldiers are deployed, their commanders know how to get them moving for exercise purposes, if they can do it safely," MacKinnon says. "But this is an effort to give soldiers a tool to help improve their strength, regardless of their location. They can use the tubing and guide in a tent, if they have to."

U.S. Coast Guard

In July, the Coast Guard initiated a new fitness program that expands on the branch's longtime maximum allowable weight standards. All 38,000 active-duty and 8,000 reserve members of the Coast Guard are required to maintain a certain weight based on standards developed by the Coast Guard. Individuals who weigh within their allowable limit must submit a fitness plan to their unit supervisor, explaining how they plan to maintain that weight, while those whose weight exceeds their allowable limit must meet with their supervisor to discuss a fitness plan that will help them get back into military-readiness shape. They are given a time frame of one week per pound they are overweight to lose the excess weight, or they face discharge.

As part of the new fitness mandate from Admiral Thomas Collins, commandant of the Coast Guard, all members must also spend three duty hours each week exercising. A unit health promotion coordinator or one of 17 regional health promotion managers supervises those members who are trying to lose weight. At a minimum, the fitness plan, regardless of weight, should include "vigorous" cardiovascular endurance training three times a week for 30 minutes and strength training one to three times a week, according to Collins' directive.

The first semi-annual weigh-in for all members is this month, followed by another one in April. "We're not weight Nazis," says Lt. Tanya Schneider, program manager for the Coast Guard's health promotions division. "We're just trying to help people live healthier lives. The existing maximum allowable weight standards were not being enforced - that was blatantly obvious. People were not being weighed in before reporting to training schools or assignments, and then being sent home later because they didn't fall within the guidelines."

Schneider says the new program aims to give more responsibility for personal health and fitness to both individuals and their supervisors, who now have a duty to ensure that their unit members are meeting Coast Guard standards. "Previously, we just told people who didn't meet the standards, 'OK, lose the weight.' We didn't tell them how," she says.

Unlike the Air Force, however, the Coast Guard likely won't be providing its members with the incentive of new or renovated fitness centers anytime soon. Not all Coast Guard units and ships even have equipped fitness centers. Those that do will have to make do with their existing facilities, Schneider says. "I think people are excited about the opportunity to work out during their work day," she says. "But for some people, exercise is going to be walking laps on the flight deck."

U.S. Marine Corps

Of all the Armed Forces, the Marine Corps is generally considered to be the U.S. military's fittest, in part because fitness is embedded in the Marines' culture. All new recruits, who number about 38,000 to 40,000 each year, must undergo 12 weeks of rigorous training at Marine Corps Recruit Training Depots at Parris Island, S.C., or San Diego. Their company commanders, drill instructors, martial arts instructors and other Marines personnel oversee the training, which involves running more than 50 miles, hiking more than 40 miles, basic combat water survival skills and what's known as "The Crucible" - a 54-hour endurance test of mental and physical strength punctuated by food and sleep deprivation.

As can be expected, musculoskeletal injuries are common during this three-month period. "Not everybody who comes to us, no matter how motivated and how fit, has the physical and mental character makeup to become a U.S. Marine," McGuire says. "SMIPP is designed to mitigate risk whenever we can in transforming civilians into Marines. We're also trying to ensure that when an individual becomes hurt in the process of that transformation that they're given every opportunity to return to training in as quick and medically safe a manner as possible."

SMIPP launched in 2003 and spreads eight ATCs across five Marine Corps training facilities. The ATCs work with Marine commanders at camps for new recruits and officers in training to suggest changes in tactics, techniques, policies and procedures. "This doesn't mean that we've made anything softer," McGuire says. "But I can certainly say that the commanding officers who are working with the certified athletic trainers now understand that reducing running or hiking mileage will make people faster in the long run while reducing injuries at the same time. There is a greater acceptance that 'harder' is not always the best way to turn a civilian into a service member."

While McGuire is reluctant to put a specific dollar figure on the cost of SMIPP, he says that the annual savings in medical expenses and associated costs "far outdistances" the amount the Marine Corps spent on the program. "Let me put it this way: At last fall's Officer Candidates School, there was nearly a 50 percent decrease in medical attrition compared to previous years."

Although considered a pilot program, SMIPP's success has assured its continuation at entry-level training sites, McGuire says. "The possibility of expanding it to the operating forces is unknown at this point," he adds. "But I think it just makes sense."

U.S. Navy

The annual Healthfest at Naval Air Station Oceana's fitness center in Virginia Beach, Va., took place in May and marked the official kickoff of the "Get Moving Navy" pilot program. The impetus for this campaign, which could eventually affect all of the Navy's 705,000 active-duty personnel, reservists and civilian employees (plus retirees), was the Department of Defense's 2002 "Survey of HealthRelated Behaviors Among Military Personnel," which revealed an increasing number of military personnel classified as overweight or obese - results that are in line with national trends toward obesity.

"This is not just a Navy problem," Settles says, citing a May 2004 study released by the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention that indicates high school juniors and seniors are less active than younger teens. "Guess when we get them. Then we adopt the problems of the nation, and it does impact our readiness."

Although "Get Moving Navy" is intended for individuals of all ages, it is targeting personnel up to age 30. Almost 80 percent of recruits who exceed military accession weight-for-height standards upon entering the Navy leave before they complete their first enlistment term, according to U.S. Navy documents. That's why one aspect of "Get Moving Navy," which is more stringent than the Coast Guard's new fitness program and arguably more challenging than the Air Force's "Fit to Fight" campaign, mandates moderate-intensity physical activity for at least 30 minutes five or more days a week.

In addition to workout regimens, program officials at Oceana have created a comprehensive approach to developing, tracking and marketing base-wide practices and initiatives that promote increased physical activity and improved nutrition behaviors. After the initial pilot period, which runs from March to the end of this year, plans call for expanding "Get Moving Navy" throughout the entire branch via regionalized programs such as the one at Oceana, incorporating posters, flyers and competitions encouraging participants to meet their fitness and nutrition goals. (In mid-August, officials at the Navy Environmental Health Center briefed the other branches on "Get Moving Navy" at the Military Force Health Protection Conference in Albuquerque, N.M.)

Settles says she hopes "Get Moving Navy" and recent programs initiated by other branches of the military not only make military personnel fitter, but also safer. "When they're sitting there, looking at a sonar for 12, 14, 16 hours, they've got to keep their energy up," she says. "That's what the sailors tell us. They've got to exercise so they can stay focused, not so they can run faster. This is mission essential."