A Japanese-American Community Banks on Basketball as a Means to Retain its Identity

It's a wonder that members of Southern California's Japanese-American community have managed to continue a decades-old tradition that emerged during World War II and the years that followed - a tradition that finds its roots on the maple floors of a basketball court.

"Sixty or 70 years ago, when Japanese-Americans were barred from playing in other leagues, they set up their own leagues," says Bill Watanabe, executive director of the Little Tokyo Service Center, a Los Angeles-based nonprofit organization offering Japanese-American community resources. During the period when they were heavily discriminated against in L.A., Japanese-American youths were not allowed to play basketball at their schools or in city leagues because of their smaller stature. "It's a lot like those 6-foot-and-under leagues," Watanabe continues. "The Japanese-American leagues were set up so people could feel like they could compete."

The leagues continue to flourish in communities all over the greater L.A. area. But according to Watanabe, league organizers often have difficulty securing playing time at the overcrowded gymnasiums in their respective communities. He believes the solution is to build a recreation center in Little Tokyo, the home of Japanese-American culture in Southern California.

The downtown L.A. neighborhood has enjoyed a colorful 120-year history, but over the past 10 years, Little Tokyo has seen a cultural and economic decline. Japanese investors who helped bolster the community have experienced financial difficulties, forcing them to cut their economic ties to the area. As a result, tourist-friendly developments - restaurants, gift shops and parking lots among them - have begun to replace the neighborhood's authentic cafés and quaint storefronts.

Watanabe believes the proposed recreation center will help infuse Little Tokyo with a long-overdue boost of energy. "We feel a recreation center will help meet a need in the community," he says. "It will provide facilities for basketball, volleyball and martial arts. Those are very important elements of our community's culture."

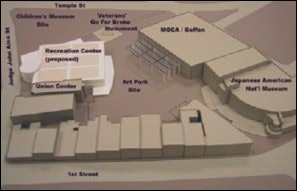

For two years, the LTSC has focused its attention on a small plot of land owned by the City of Los Angeles that sits on the First Street North block of Little Tokyo. "For the past several years, we've done a broad sweep of every possible site in the area, and there aren't many that can accommodate a 40,000-square-foot facility," says Watanabe. He points to environmental issues, poor timing and uncooperative land developers as reasons why other downtown sites did not pan out. "Now we are competing with three museums that all want to be on that site."

Those museums - the Japanese-American National Museum, the Geffen Museum of Contemporary Art and the Children's Museum of Los Angeles - and the Union Center for the Arts (a performing arts venue) are all stakeholders on the First Street North block. Three of them have been residents of the block for approximately 10 years, while the Children's Museum is planning to relocate to First Street North from another downtown area after building a 100,000 square-foot facility on the north end of the block. A small art plaza and a World War II memorial to Japanese-American veterans already exist in the block's center, as well, and with the addition of the Children's Museum, the other museums hope to develop a much larger art park.

"Essentially, the space is being fitted for the Central Avenue Art Park," says Chris Komai, the Japanese-American National Museum's public information officer. "This park would connect the different stakeholders." That is, every stakeholder except the recreation center, a situation that Komai says is no group's fault but its own. "I think part of it is that their plan and the plan for the Central Avenue Art Park aren't necessarily compatible," he says. "Does the recreation center have to go in the art park?"

Watanabe believes that all parties - the LTSC included - can come to a compromise. "Our position is to have both the recreation center and the Children's Museum, but just make the art park smaller," he says. "When the Children's Museum told us they needed a site, we said, 'Fine, but we don't want your project to keep us from being able to build our center.' "

Despite all the attention paid to the proposed art park's size, Komai suggests the focus be directed to a more significant concern. "I think the ultimate question is: Does the recreation center have the wherewithal to build itself?"

According to Watanabe, it would cost the LTSC approximately $9 million to build the recreation center, $750,000 of which has already been raised. The LTSC hopes to secure a long-term lease from the city, available in 50- or 100 -year terms at the rate of $1 a year. It is unlikely, though, that City Hall will agree to such a lease if the LTSC cannot show it is capable of raising the capital necessary to build the center.

Komai remembers the obstacles his organization faced in obtaining a city lease when it first planned to move to the First Street North block. "We renovated a historic Buddhist temple in 1992, and it cost us $13 million," says Komai of the Japanese-American National Museum's current facility. "The city would not let us move forward until we had a high percentage of the money - at least 50 percent - in hand. In other words, we couldn't begin that project until that money was in the bank and we could show the city that we were serious."

While Watanabe says the LTSC is indeed very serious about its project, he adds that it has been difficult to develop a consistent fund-raising plan for the recreation center. "If you don't have a site, it's hard to raise the money," he says. "Would you give money to a program that doesn't have the property? I wouldn't." Despite that challenge, Watanabe is fairly confident the LTSC can raise the funds necessary in two years. "We've talked with some corporations and foundations," he says. "And financially, they feel this is something they'd like to support."

Perhaps the LTSC could use a business-savvy, well-connected board of directors, such as the ones that control the respective destinies of the Japanese-American National Museum and the Children's Museum. Seated on the former's board of trustees are high-ranking corporate executives, former politicians, powerful attorneys and even a famous actor. The Children's Museum's board of governors has much the same composition, and according to its chairman, Douglas Ring, is one of the most sought-after board memberships. Ring says his board's esteemed reputation helped the museum reach an agreement with City Hall, securing 50 -year land leases for its project on the First Street North site, and for another facility in the San Fernando Valley, as well.

Another problem facing the LTSC has nothing to do with its lack of finances or the neighboring museums, but instead concerns the basketball leagues themselves. Ring - an attorney by trade - says that the proposed recreation center might never have the opportunity to build on city land if leagues using its facilities are suspected of excluding non-Japanese-Americans. "If that is true, then they can't build on city property because of anti-discrimination laws," says Ring. "When a 6-foot-2 African-American kid wants to join one of these teams, they can't say, 'You can't because you're not Japanese.' "

Watanabe says that while a few leagues allow Japanese-American youths only, all is not what it seems. "We're saying, 'It looks like that, but there's a community connection here,' " he says. "It's part of a place where Japanese-American kids can do things with other Japanese-American kids. It's a cultural thing." Watanabe also points to local martial arts clubs that could possibly use the recreation center. "In many of the judo and karate clubs, the participants are predominately non-Japanese," he says. "We feel our facility will be multicultural and very open."

While hopes for the proposed recreation center remain high, Howard Nishimura, president of the Little Tokyo Community Council, fears that it will never be built. If it's not, Nishimura says the real culprit might not be the museums or the city government at all, but rather his own community. "Our people pull in so many different directions for their respective areas," he says of Japanese-Americans who have migrated away from Little Tokyo to the outlying L.A. suburbs. "They don't really want to put their money into Little Tokyo. They want to build community centers in their own areas. We need to try to do something down here in Little Tokyo, before we have no Little Tokyo left."