Topeka School Officials Leave Little to Chance With a New $17 Million Sports Park

After four years of planning, nearly 100 meetings with constituents and a massive public-relations campaign, public school officials in Topeka, Kan., finally broke ground in March on a $17 million sports complex. When complete, it will not only serve the 4,000 students in the city's three high schools, but also the surrounding community of 125,000 people.

As with most projects of this magnitude, dissent was expected. "Any time you spend that amount of money on athletics, you're going to get some raised eyebrows," says Brad Stauffer, director of communications for Topeka Unified School District 501. That said, 58 percent of Topeka's voters - many of whom don't have school-age children - approved a $24.5 million bond issue last year for both the Topeka Sports Park and new classrooms in elementary and magnet schools.

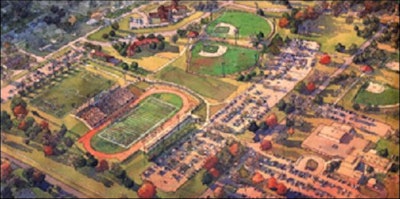

The sports complex - which will include a 6,000-seat football stadium and a 2,000-seat soccer stadium; an eight-lane all-weather running track; a 1,000-seat natatorium with an eight-lane, 50-meter pool and separate diving well; and fully equipped baseball and softball fields - may not be the most expensive high school athletic facility built in Kansas or elsewhere. Its $17 million price tag, though, is still more than most school districts can fathom. Even new stadiums in football-crazy Texas cost less than that.

But with the sports facilities at Topeka, Topeka West and Highland Park high schools in dire shape, district officials knew they had to do something. All three schools share an aging football stadium built in the 1930s, and Topeka High boasts the district's only swimming pool, but it's 45 years old and unable to host competitions. As a result, the district shells out nearly $30,000 a year to rent additional football and swimming facilities from nearby Washburn University. Meanwhile, soccer fields at the schools lack adequate seating, rest rooms and other amenities, and a shortage of baseball and softball fields often results in scheduling conflicts.

Rather than undertake renovation projects on each campus, district officials opted for a well-known piece of park-like land formerly occupied by the Topeka State Hospital mental institution and located near all three schools. "We think we paid a fair price for the property," Stauffer says of the $1 million, 40-acre purchase, which was entirely funded using proceeds from the district's pouring-rights contract with Pepsi. "Since the mid-'90s, we have had our eye on that property. We also looked at building on property we currently owned, to possibly spread the facilities throughout town. But we just didn't have enough property to do it right."

The entire project has been a lesson in how to do things right - a case study in how to pitch a major sports project by assuaging the concerns of special-interest groups and garnering the support of skeptical taxpayers.

From the beginning, district officials and representatives from GLPM Architects in Lawrence, Kan., recognized the challenge they faced in getting enough older voters to agree with their vision. In fact, their research indicated that if the bond issue even passed, it would be by no more than 55 percent. "That it passed at all is a moral victory," says GLPM's Craig Penzler, the principal in charge of the project.

The district implemented a multilevel strategy to garner public support, which included holding three public hearings, sponsoring about 90 community meetings with various civic and parent groups, distributing flyers to all of the city's registered voters, producing television commercials and creating a video that featured computer-animated images of the park. "If people actually see something, they get the sense of how great that something can be," Stauffer says, calling the taxpayers' vote of confidence on this project "a rare commitment."

Semantics also played a role in the district's strategy, as project officials changed the facility's identification from a "complex" to a "park" early on in an effort to mute local environmentalists' concerns. "We wanted to concentrate on maintaining the green space, so we saved more than 260 trees and designed a walking trail around the park," Penzler says. "And we designed the facilities to hold more people than they needed to, so Topeka could host state championships, NCAA regional competitions and the Special Olympics. By convincing voters that we could take the facility to that next level, all of a sudden, this wasn't just something for the schools anymore. It was a community-enhancement project. That's when people started buying into it. I think some civic pride developed."

In the end, the 20-year bond issue wound up costing taxpayers, on average, an additional $2.40 annually on a $100,000 house. As the project's "frequently asked questions" page on the district's web site states, "You'd pay more for a loaf of bread."

Topeka officials may still be in for a rude awakening after the sports park actually opens. Voters in Overland Park's Blue Valley Unified School District, who approved a bond issue (and bond retirements) in 1998 for $43 million Blue Valley West High School, didn't see a tax increase at all. But that didn't stop them from complaining after the lavish sports facilities opened. One Kansas City Star reader suggested in a letter to the editor when Blue Valley West opened that all students should show up at the athletic fields on the first day of classes. Those who were not athletes could then head for the conventional classrooms for an "old-fashioned education," offered the letter-writer, while the student-athletes could remain at the complex until they graduate.

Achieving balance between academics and athletics has always been a struggle - one that Topeka school officials acknowledged from Day One. The project's FAQ page on the district's web site addresses the issue of why more money is being spent on sports this time than on academics by explaining that more than $1 million was spent on athletic facilities during the past two decades, while almost $60 million was spent on "educational enhancements" - including new elementary schools, air conditioning and technology infrastructure.

In a later item on the FAQ page, the district attempts to answer critics who note that all students benefit from academic improvements, while relatively few profit from new athletic facilities. "For some students, [athletics participation] provides the motivation to succeed academically and in some cases stay in school," the site reads. "Band members, cheerleaders, drill teams, etc. all will participate in activities at the sports park. A substantial percentage of students will enjoy using and attending athletic events at the sports park."

To further allay the public's financial concerns, district leaders plan to implement an "aggressive" marketing campaign promoting facility rentals to outside groups. The revenue generated by these rentals is expected to fund the park's annual operations and maintenance budget, including personnel, which is estimated at $250,000.

Meanwhile, construction of the Topeka Sports Park's football and soccer stadiums is slated for completion by next fall, and the other facilities will be finished sometime in 2004. That means district officials have a little longer than a year to find out if their project's slogan, "Great Starts, Great Finishes," works as effectively as the rest of their strategy has thus far.