Advances in field-surface technology have resulted in natural grass and synthetic turf systems that deliver durability and extended use.

The demand for athletic facilities to host not only a variety of sporting events, but also marching-band competitions, rock concerts and even community flea markets and car sales, fueled the rise of the multipurpose stadium and its most potent symbol-the synthetic field. From that moment on, it was a two-team race to develop the perfect field system, and to a certain extent, both synthetic turf and natural grass are winning. Synthetic turf manufacturers have made steady progress to improve the playability and durability of their products over the last 30 years, and now a number of natural-grass suppliers have made equally impressive strides in the development of surfaces that also better meet multipurpose demands.

From portable grass that unrolls as a cover for concrete floors and parking lots, to grass tiles with roots that are reinforced and stabilized with synthetic fibers, to systems that mix grass with synthetic fibers woven or stitched into a backing, progress is breathing new life into something that's literally as old as dirt. Many of these advances allow sections of worn surface to be replaced without tearing up an entire field, and the whole surface usually can be removed or installed in less than 24 hours.

"The grass-surfaces industry has been heading this way for 30 years," says John Stier, an assistant professor of turfgrass science at the University of Wisconsin and one of the country's leading grass researchers.

At the same time natural-grass suppliers are becoming more responsive to facilities' needs, synthetic-turf makers have found ways to better respond to athletes' needs. At least three companies have begun using a mix of rubber or rubber-and-sand fill beneath a surface of synthetic blades in an attempt to provide more cushioning than traditional synthetic fields. The fabricated blades above the surface have also changed, giving off a slippery, nonabrasive touch while combining solid footing and torque release-leading manufacturers to claim their products look and feel like natural grass.

Improvements to synthetic turf and advancements in natural grass have occurred largely in an effort to further woo facility operators with the temptation of extended usage, which allows them to develop new revenue streams by hosting multiple events. "Everything is driven by revenue potential," says one natural-grass supplier. "Still, it's a slow go. Teams, municipalities and stadium operators want to host all of these events, but they don't want to pay the dollars to have these types of systems installed."

Indeed, costs for such systems begin well into the six-figure range-a price tag many facility operators with limited funds and staff have a tough time swallowing. Just as each field has its own distinct needs (and restrictions) based on its amount of use, the size of its groundskeeping staff and its operations budget, each field surface has its own characteristics. But the success of a few high-profile installations in handling wear and the elements in their first few years could eventually leave a lasting impact at all levels-municipal, high school, collegiate and pro-especially as costs of new technology come down. Says Stier, "There still is a fear of the unknown-and, in a sense, the unproven."

The portable grass field's toughest test is on tap for Sept. 3, when the Meadowlands hosts its first regular-season NFL game on natural grass.

For the past four years, interlocking plastic trays containing 46-inch-square modules of natural grass were brought into Giants Stadium whenever the New York-New Jersey MetroStars of Major League Soccer took the field. But they were always removed for other events, including NFL regular-season games, and stored in the Meadowlands parking lot while the New York Giants and Jets each played on synthetic turf. This season, however, both NFL teams will make the switch to portable natural grass, which will be heated and cooled by an underground system. The 6,000 or so trays, each with bottom drains and air outlets, will be rotated as wear and tear demand using an inventory of substitute grass trays stored and nurtured in the parking lot.

All told, the Meadowlands will house enough trays to supply grass to 2.2 football fields-which should see the facility through the 160 events it hosts each year, says Chris Scott, president of GreenTech® Inc., which manufactures the ITM turf modules in use at Giants Stadium. "I felt like this made sense," Scott says about the concept of using trays, which allow for root-zone depths of between 7.5 and 11 inches. "Places like Wimbledon, heavily used golf tee-off areas and multiuse stadiums were the first applications that came to mind." Is it a gamble? Sure. But that shouldn't stand in the way of progress, says Suz Trusty, information coordinator for the Sports Turf Managers Association. "Because a lot of these turf developments are so new, if you make the decision to go with one, you have to stand up for it and say why it's the best surface for your team and your needs. It is a gamble. But so was everything else that was new at one time or another during the past 15 or 20 years."

Like many of the companies it competes against, GreenTech was around for a few years before it made a significant push into the athletic-field market. The time is ripe, Scott says.

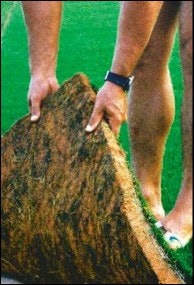

That might explain why an abundance of leading suppliers-all developing systems claiming to better reinforce the root zone and extend usage-have hit the market in recent years with alternate paths to the same destination. Hummer Turfgrass Systems Inc., for example, also grows grass in trays that allow for drainage and air movement. But the trays are removed from underneath the 7-by-7-foot GrasstilesTM prior to installation. Tiles are rotated or removed using a specialized lifter that grips individual pieces. Further differentiating Grasstiles from GreenTech is a 2-inch-thick root mass reinforced and stabilized with shredded carpet fibers, allowing for additional wear, says Webb Cook, Hummer's vice president of sales and marketing.

Synthetic reinforcements-usually made with a small percentage of polypropylene or similar material that will not break down in the soil-play a role in several portable grass surfaces that are considered 100 percent natural by their suppliers. Because the majority of the additional synthetic material is inserted below the grass surface for root reinforcement and additional wear resistance, suppliers reason that it is not interfering with the naturalness of the playing surface itself. But wouldn't the often-referred-to term "hybrid"-meaning a blend of natural and synthetic elements-be a better descriptor? "It really isn't a bad term," says Mark Heinlein, senior vice president of The Motz Group, another natural-grass supplier. "But a growing number of companies in that area are making dissimilar products."

Indeed, variation is the name of the game. The Motz Group's TS-II™ is a natural-grass system stabilized with a combination of sand-filled, fibrillated synthetic tufts and a dual-component backing of biodegradable fibers and plastic mesh. The matrix shelters the vegetative parts of the grass plant that are essential to rapid growth and recuperation, according to the company, while the grass roots intertwine with the tufts and grow down through the plastic mesh. If the turf canopy wears away, the sand-filled synthetic matrix continues to provide a consistent playing surface.

DD GrassMaster, from Desso DLW Sports International, is another naturalgrass surface reinforced with synthetic fibers. But rather than being stitched into a backing cloth, the fibers are implanted into the ground using a massive device that resembles a sewing machine. The system is still more popular in its native Europe, but U.S. markets are opening up, says Richard McDonald, product manager for DD GrassMaster. SportGrass® Inc. is also making headway, although after a few initial setbacks.

The SportGrass system, like TS-II, grows natural grass in a layer of amended sand with synthetic grass blades tufted into a woven backing. The synthetic blades are slit to allow the root system to grow through both the fibers and horizontal backing. Two years ago, changes were made to the system to improve its performance. Instead of a tight, woven polypropylene backing, the backing now features bonded polypropylene that looks like stretched metal and allows for sand-to-sand contact, says Brian Wood, general manager of SportGrass. Also, fewer fibers per square inch now make for better cleat penetration and more room for the natural grass to take root, he says. SportGrass has also developed a prototype of a portable rollout field that is being tested in southern Virginia and could hit the market next spring.

Already available for portable use is STN 2000, from Southern Turf Nurseries. The 2-inch-thick natural-grass surface, which contains no synthetic backing or fibers, can be rolled out over any surface - even concrete-because its roots are trained to grow on top of a plastic barrier, similar to roots in a potted plant, says Don Roberts, company vice president.

After an event, it may be rolled up and stored on-site or shipped to a farm or other holding area for continued growth until it's needed again.

Thomas Bros. Grass, a division of Turf-Grass America Co., also is hard at work creating a portable turf (this one backed with synthetic materials) that will be harvested in 8-foot rolls for temporary installations, according to Dwane Smith, sports field manager for Thomas Bros. Already, the company offers a variety of field options as a supplier of and contractor for StrathAyr Turf Systems Pty.

Ltd., an Australian grower of natural grass systems that recently completed its first installation in the United States. StrathAyr's most portable product is SquAyers™, 4-inch-thick slabs of mature natural grass used for the quick repair of damaged or worn surfaces. Like many other surface systems, SquAyers are reinforced with a mesh backing to help maintain their shape and reduce soil compaction. They come in either 4-by-4-foot pieces or 8-by-20-foot sections. Even Southwest Recreational Industries Inc., best known for its all-synthetic surface AstroTurf®, has stepped into the natural-grass market. AstroGrass® allows natural grass to grow through a biodegradable, woven synthetic-turf fabric, says Troy Squires, vice president of marketing for Southwest.

Despite advances in natural grass, officials at Southwest and FieldTurf™-the industry's most-visible synthetic-turf suppliers-each report they've installed more fields than ever in recent years, expanding their reach from professional and major-college stadiums to municipal facilities, small colleges and high schools. And while synthetic turf might not be portable, as are some of the newer natural grass systems, it does satisfy facility operators' desire for extended use.

FieldTurf, originally developed as a golf product for indoor sports complexes in the late 1980s and early 1990s, blends and tufts polyethylene and polypropylene fibers into a permeable surface backing. Each synthetic grass fiber is placed so as to create a pattern of natural grass. The fill is made from sand and ground rubber, which surround each fiber much like soil holds a blade of grass. At press time, FieldTurf was set to wrap up contracts with at least two facilities to install a new modular system, says John Gilman, FieldTurf CEO. That system features the same composition as regular FieldTurf, only cut into transportable pieces. The concept performs a function similar to what GreenTech is doing with natural grass in Giants Stadium, Gilman says.

Meanwhile, AstroPlay®-Southwest's version of a synthetic surface featuring elongated blade fibers, but without the sand fill-features a combination of rubber and nylon fibers mixed with longer polyolefin strands. Company officials say the rubber and nylon enhance drainage, reduce compaction and add resilience. Along those same lines, SafePlay International, another synthetic-turf supplier, recently introduced the ComforTurf infill system, which uses the patentpending DuraBlend process to create a shock pad within the polyethylene turf fibers to form a flexible but consistent base layer upon which rubber granules can then be added.

Just as Southwest has joined the natural-grass ranks, Hummer last year introduced an all-synthetic surface to supplement its natural-grass business and give facility operators another option. SofSportTM is a sand-and-rubberfilled synthetic surface that's installed over a 10-millimeter rubber pad for additional resiliency and includes more synthetic-fiber strands than similar systems, Cook says, to make the surface even more substantial and lifelike. "The best natural-grass fields that people play on are nice and lush," he says.

But will more strands result in fewer injuries? Are lush, natural-grass fields safer? Despite a plethora of opinions on knee, ankle, head, neck, brain and spinal cord injuries, never-ending debates about their causes and numerous surveys supporting one surface over the other, official and independent medical studies that make a blanket recommendation are tough to come by. "You can't win one way or the other," says Beth Kedrowske, research coordinator at The Institute for Preventive Sports Medicine, a research facility in Ann Arbor, Mich. "You're going to have injuries either way, because of the contact nature of sports." Most facility operators are going to spend the time and money to research a surface's safety aspects before signing a contract, suppliers say. Some even go so far as to blame what sportscasters say on television for forming biased public opinions about synthetic turf.

A battle of sorts has erupted, particularly over the need for synthetic-turf safety standards (as there are in Europe), and more specifically, the need for padding underneath those surfaces. Is it necessary? The folks at Southwest, whose AstroPlay sports an all-rubber fill and whose latest AstroTurf surface (12-2000) rests on top of a 26-millimeter rubber or rubber/stone pad, say yes. "The concept of something feeling soft and something feeling safe or shockabsorbent is different," Squires says.

"You can have something that feels very soft, but if you hit it with a lot of force, you bottom out and you're in contact with whatever's underneath it."

Gilman contends that a pad is unnecessary in Fieldturf's patented rubberand-sand-filled system. "The whole development of FieldTurf has been to match natural grass," he says. "If somebody comes to me and tells me that natural grass is unsafe, fine, we're going to have to change FieldTurf." Cook says Hummer is too small of a player right now in the synthetic-turf market to get involved in the debate.

But he adds he would support some method of setting safety standards, as long as they were fair and could be agreed upon by all parties involved.

While the murky safety issue will undoubtedly remain a hot topic, there are other issues that could also impact the direction of both the natural-grass and synthetic-turf markets.

On the natural-grass front, research involving cold tolerances of certain species, use of herbicides and pesticides and other topics continues at major universities across the country. Meanwhile, synthetic-turf manufacturers are bracing themselves for a flood of competitors that realize a mix of rubber or rubberand-sand fill beneath a surface of synthetic blades works well-and sells. In this rush to hit the market, however, some manufacturers might not smooth the bumps in their blends before making sales. The same could be said of upstart natural-grass suppliers.

"The Achilles' heel is that a lot of these new companies do not want to invest in a lot of research of their products before they're sold," Stier says. "That could lead to a setback." In the case of SportGrass, which suffered two high-profile removals from the NFL last fall, at least one setback has been erased. The Baltimore Ravens-which pulled the surface last season at PSINet Stadium-has committed to installing SportGrass in a permanent practice facility when it's built, Wood says. "If you want to consider Green Bay and Baltimore flops, that's fine," he adds. "But we've gone through all the bumps and bruises that any company could ever receive, and we've made it through."

Bumps and bruises are expected in what some companies are calling an ongoing "turf war." But price fights and an abundance of products that accomplish similar goals in different ways could backfire on the market, observers say. Still, in its most basic and purest form, competition breeds innovation. In the case of sports fields, such advancements can ultimately-and quite literally-change the ways operators run facilities and athletes play games. "The field will no longer be a determining factor in the game," DD GrassMaster's McDonald predicts.

"There'll be no slips because of bad traction. There'll be no bad bounces because of divots. But I don't think we'll ever actually have a perfect field." Doesn't hurt to keep trying, though.