As indoor climbing continues its ascension, facility operators must make informed decisions regarding size, style and safety.

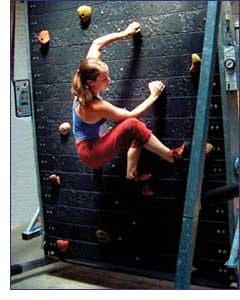

Photo of girl climbing on rotating wall

Photo of girl climbing on rotating wall

And rebuild, she has. A portion of the club reopened within 72 hours of the fire, which started in a faulty heating unit of the men's sauna and caused at least $4 million in damage but, amazingly, injured no one.

This year, Norton Pines, originally a 96,000-square-foot facility, underwent major renovations and is on track to reopen in October with nearly 40,000 square feet of additional space. Central to the renovation was the $140,000 construction and installation of two climbing walls: a 20-footer designed for kids, and another one that extends approximately 35 feet toward the facility's peak and targets adults of all climbing abilities.

"I did not have any space for a climbing wall before," Pemberton says. "It took me about eight weeks to decide to tear the old building down and start with a new pre-engineered building. At that point, I knew I had much more space available to me, and that's when I started researching climbing walls."

In June 2002, Pete Morgan, general manager of the Burke (Va.) Racquet & Swim Club, was in a similar situation. He decided to convert one of his facility's four racquetball courts into a climbing gym and installed ten 20-foot-tall modular climbing walls with automatic belaying systems. Originally intended to be open to climbers at almost any time of the day, the club's climbing room is now almost entirely booked with parties and a variety of programming aimed at youths.

"I would visit some nice collegiate rec centers, see some neat climbing facades and my mind would just start working," says Morgan, who says he would add even more climbing elements to his facility if he had the space. "I spent seven or eight months just crunching numbers -- installation and labor costs, liability issues, and the potential loss of revenue from a fairly benign space. Those were big considerations."

Climbing, clearly, is big business.

"Climbing is no longer the exclusive domain of the rock jock," says Jim Stiehl, a professor in the School of Sport and Exercise Science at the University of Northern Colorado and author of the recently published book, Climbing Walls: A Complete Guide (Human Kinetics). "Kids are climbing. Older adults are climbing. People who have disabilities are climbing. I think a lot of facilities are trying to make themselves more accessible to a wider spectrum of abilities."

Indeed, statistics indicate that more young people than ever are climbing today: 60 percent of all artificial wall-climbing participants are 17 years old or younger, with 6- to 11-year-olds the most frequent participants, according to SGMA International. And research recently released by the Outdoor Industry Association indicates that participation in artificial rock climbing among 16- to 24-year-olds has increased significantly since 2002. But the climbing wall business is getting a boost from older participants, too -- thanks in part to wall cards that are posted at eye level featuring instructions and diagrams that explain in non-threatening terms climbing techniques and routes in much the same way similar cards illustrate proper fitness equipment usage.

"I know that the walls are going to be key to attracting more memberships," Pemberton says. "We've never been able to do many youth activities, and we relied on area YMCAs to take charge of activities for kids from 6 to 14 years old. We are banking on the walls to bring in more families."

"We're seeing an industry that has proven itself over the last 25 to 30 years, from when the first climbing walls were built in Europe," says Rich Cook, general manager of Boulder, Colo.-based Eldorado Wall Co. "Climbing is an accessible sport that has appeal for a variety of reasons. It's mental, it's physical, it's spiritual -- all of those things factor into its popularity. It's a real gestalt activity."

"In the '90s, climbing in the United States was sort of a renegade, anti-social thing, and then it turned into a radical, MTV, extreme sort of thing, and now it's almost to the point where it is in Europe. People are realizing that this is a great thing to do, and anybody can do it," adds Adam Koberna, director of marketing and sales for climbing wall manufacturer Entre Prises USA in Bend, Ore. "You can climb hard and get a really good workout, or you can just go and have fun. Even though there's always an aspect of danger, climbing is not seen as intense as it once was on a marketing and image level. It's a little more palatable to the general public now."

Nevertheless, facility operators face plenty of questions when making the decision to install a new climbing structure. Will it appeal to a broad range of users? How often will it see action once the initial excitement wears off? How will it be staffed? What if actual revenue doesn't live up to projections?

But thanks to the popularity of bouldering and automatic-belay systems -- plus the development of the Climbing Wall Association, a risk-management, standards-setting industry group -- operators of all types of facilities now enjoy greater freedom when purchasing and installing a wall.

That wasn't always the case. Many early climbing walls featured only brick construction, leaving little room for creativity. Movable handholds, sophisticated polymer panel wall systems and shell concrete climbing structures followed, with climbing walls soon being used to make grand architectural statements, especially in college recreation centers. Today, structures take many forms and have worked their way into the fitness fabric of municipal and church recreation centers, YMCAs, health clubs, elementary and high schools, camps and other facilities.

"Architects have a ton of influence on how much somebody spends on a climbing wall or how successful a climbing wall will be," Koberna says. "It all depends on when they bring a climbing wall manufacturer on board and what kind of space they give that manufacturer. Higher-end climbing walls need to be installed through a true design-build process. So the earlier manufacturers get involved, the better."

Facility operators need to look at the demographics of their current membership and ask themselves why they are even in the market for a climbing wall. Some simply want the "wow" factor and opt for the most impressive-looking structure their budget can handle, while others are serious about using the wall to recruit new members while not alienating existing members. "The question is, 'What do you want to achieve with your wall?' It has to be viewed as a long-term investment," says Russell Moy, president of Pyramide USA, a climbing wall manufacturer in Leesburg, Va.

Usage patterns (and climbing habits) will change over time, he says, so a wall must be able to adapt. Moy also draws parallels between the climbing wall industry and the skate park industry, citing a shift from plywood-based ramps and other skate park elements to reconfigurable modular structures. "The youths who are skateboarding today are going to be doing things at skate parks in 10 years that we think inconceivable now," he says. "It's the same with climbing walls."

Walls come in several different styles to meet a variety of different needs, but most are made from a combination of plywood, polymer cement, fiberglass, glass fiber reinforced concrete or shell concrete. (A few walls in Europe are even constructed of ice, although no facilities in the United States have yet to install a permanent ice wall, given the complicated and expensive nature of such walls' refrigeration systems.) Climbing walls are typically crafted in panels and then pieced together, while some larger structures are hand-sculpted on site. The type of wall often determines the materials used. Among the most popular types:

- Free-form structures: These structures boast the natural look and texture of real rock and can be shaped to meet any specification. They can be incorporated into a wall or used as a freestanding element.

- Panel systems: Usually attached to steel frames or other support structures, panels allow for any inclination and wall profile -- making overhangs and even ceilings traversable.

- Towers and pinnacles: Available in either freestanding or wall-mounted versions with 180- or 360-degree usability, these space-saving structures can be installed indoors or out.

- Racquetball/squash court conversions: Most conversions are turnkey and can fill one, two or three sides of an underused court.

Manufacturers also offer a variety of specialty and hybrid walls, including partially submerged water walls for swimming pools, rotating walls and shorter walls for kids. Such walls often complement -- or become a less pricey alternative to -- a more traditional wall, according to Conant Brewer, president of Brewer's Ledge, a Boston-based company that manufactures both rotating and fixed walls. "People come into facilities with different skill sets and different needs," he says. "For example, if you have a 25-foot wall, you might be missing out on the people who want to bring in their kids or the elite climbers who want to train for endurance."

Bouldering walls can help solve those dilemmas. While a climbing wall isn't really effective if it's less than 20 feet tall with a surface of at least a couple hundred square feet, shorter and smaller bouldering walls can be as compact as 13 feet high by 15 or 20 feet wide. The structures don't require belays and can serve purposes as disparate as training for specific climbing disciplines and teaching basic climbing skills to beginners in a safe and non-intimidating environment. Because of their limited height, bouldering walls can be installed in locker rooms or storage areas, or in warm-up zones located near traditional climbing walls. Some models even come with built-in mats.Bouldering has become a particularly popular activity in schools.

But Nate Postma, president of St. Paul, Minn.-based wall manufacturer Nicros Inc., warns that some school administrators may think, incorrectly, that fewer injuries occur on bouldering walls than on climbing walls, simply because of the size difference. "Oftentimes, school administrators will think bouldering is safer," he says. "They presume that climbing wall belayers will fail and that people will fall and get hurt. Actually, more injuries occur on bouldering walls than they do on climbing walls. But the severity of bouldering injuries is usually much less -- a twisted ankle, a sprained wrist."

Bolt-on modular handholds used on both bouldering and climbing walls have also undergone an evolution of sorts. The most notable change is in the materials used. While resin and fillers, which tend to be brittle, were once the handhold ingredients of choice, most holds today are made of durable polyurethane (capable of withstanding a sledgehammer's blow, according to one manufacturer) and come in a variety of textures, colors and sizes. Considering that some companies manufacture more than 1,000 different holds, it's difficult to characterize the typical hold -- although the most common holds on the market (in descending order based on size) are known as roofs or jugs, slopers, edges, crimps and pinches.

Of all the recent developments in indoor climbing, however, the advent of the automatic-belay system seems to have made the greatest impact. The device, designed specifically for the recreational climbing industry, eliminates the need for an additional climber or attendant to serve as a belayer and helps minimize staffing. Morgan says an auto-belaying system was "the deal maker" in his decision to install wall panels at the Burke Racquet & Swim Club. "If you don't have auto-belays, that means you have to have a certified belayer for every climber in the gym. It would have been impossible for us to have three or four staffers in there constantly."

The system also has value for climbers working without a climbing partner, although some facilities (particularly college recreation centers) like to stress the activity's social aspects -- the "buddy system," if you will -- and either prefer to not install auto-belay systems or to limit the number of routes for which the systems can be used. Auto-belay systems, which usually cost between $2,000 and $3,000 each, require facility operators to inspect the gear daily and ship the equipment to its manufacturer for annual inspections. Should facility operators decide to install the systems, some wall manufacturers recommend that they go with at least two. Retrofits to existing walls can be as easy as clipping a system to the top-rope anchor.

"In the scope of putting in a $50,000 or $60,000 climbing wall, they're not expensive," Cook says. "They're a good value-added item."The climbing wall selection process can differ dramatically among facility operators. While Pemberton knew members of Norton Pines would welcome a climbing wall (or two), based on responses to surveys she conducted over the years, Morgan had no real indication that climbing structures would be popular in his facility. "I just knew in my gut that it would be a hit," he says. "I didn't talk to any members, because I intended it to be a surprise. Plus, I didn't want to shout it up and then disappoint people."

Regardless of the process used to gauge interest in a climbing wall, safety concerns remain even after the wall is in place. Up until a few years ago, no fewer than three industry groups existed to address engineering, safety and operational standards. Today, the Climbing Wall Industry Group, the Climbing Gym Association and the Climbing Sports Group -- once all specialty groups of the Outdoor Industry Association -- have more or less morphed into the Climbing Wall Association, a Boulder, Colo.-based nonprofit trade organization for manufacturers and facility operators. CWA, which formed in May 2003, provides training, risk-management consulting and operational standards (available at climbingwallindustry.org).

The standards focus on climber orientation, climbing procedures, facility operations and business practices, and cover everything from access and legal waivers to belay testing, record keeping, supervision and training. "The CWA was born out of necessity," says Bill Zimmermann, the association's executive director who came on board in March from the Association for Experiential Education and is otherwise not affiliated with the climbing industry.

"There needed to be a custodian for these industry standards, because there wasn't any independent organization representing the climbing industry's interests." With new climbing walls entering fitness and recreation facilities on a regular basis, it's fair to presume that some operators lack the knowledge of, say, climbing-only gym owners. That's why Zimmermann promises that the CWA's presence will increase in the coming months via the distribution of informational posters and other materials in an effort to spread safety and design knowledge.

After all, as Koberna says, "this industry is nowhere near peaking."