As more Division I-A football programs embrace premium seating, entire stadiums stand to benefit -- but is this love everlasting?

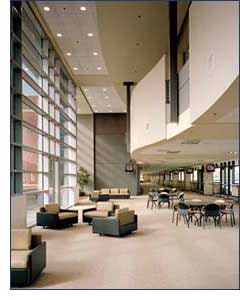

Purdue University club seats

Purdue University club seats

Not that packing these newly minted premium seating areas was a must; MSU had already surpassed its season goal of 18 leased suites and was closing in on a target 500 club seats sold. However, three separate open houses -- conducted even as carpenters were wrapping up their finishing work -- nonetheless gave major donors and regional business leaders a chance to preview a new era in the Spartan game-day experience.

"We're not panicking," assured Scott Knuth, associate director of development for MSU athletics, days before a July 27 sales event was expected to feature head football coach John L. Smith and draw 700 potential premium seat purchasers. "We're not even concerned. We're counting on moving a whole bunch of club seats and some suites, because there's a wow factor with this renovation. Once our fans see it, we think they'll buy into it. We just have to get people up there."

Up-selling fans on premium seating has become the accepted order of business for an increasing number of Division I-A football programs, from Oregon to Florida. In the

11-member Big Ten Conference alone, 10 schools have either opened premium seating since 2000 or have plans to do so before the end of the decade. The other one -- Northwestern University -- began offering something akin to modern club seating in 1997.

While institutional one-upsmanship may be at play on some level, premium seating is less about athletic department narcissism and more about economic necessity. Crumbling stadium infrastructures, ballooning payrolls and escalating scholarship costs have forced administrators to identify new revenue streams, and the contracted revenue secured through the sale of luxury suites and club seats is like money in the bank for schools looking to bring their whole operation up to speed. Says Jim Grinstead, editor of Revenues From Sports Venues, "It's not so much a situation of schools wanting to provide that luxury experience for fans as it is a need to offer that product as a way of financing other stadium improvements."

At the University of Iowa, where next year 46 suites and nearly 1,300 indoor and outdoor club seats will open at 75-year-old Kinnick Stadium, "The emphasis wasn't on the premium seats," says Jane Meyer, Iowa's senior associate director of athletics. "For us, the impetus was a deteriorating south end zone -- with rest rooms and concessions stands that have been there since the stadium was built -- that had to be replaced. That project alone would have cost us $12 million to $14 million, and athletic department revenues cannot support that kind of project. So, the way you pay for it is premium seating. That's why we built what we built."

Because premium seating often generates the most media buzz, the public can be easily misled by a renovation's price tag. At Purdue University, the actual installation of premium seating at Ross-Ade Stadium represented no more than $18 million of a three-year, $70 million renovation completed in 2003, yet income from the premium seating pays $4.3 million toward the entire project's $4.7 million annual debt service. "This is the message that I've been trying to get out to the public from the get-go, because there was this presumption that we were spending $70 million to create upscale seating for rich ticket buyers," says Glenn Tompkins, Purdue's senior associate athletic director for business.

"In fact, of the $70 million, more than $50 million was for infrastructure that benefits the average fan sitting in the stands. It's more concessions stands and rest rooms, wider seats and concourses, and improved concrete and sound -- I could go on and on. The income from the premium seating is what makes all the other benefits possible."

While premium seating is looked upon to support a lot, exactly how much premium seating a decades-old stadium and the fans who frequent it can support represent separate concerns. In some cases, premium seating can be incorporated into an existing structure almost seamlessly -- by gutting an underutilized level within a press box to make room for suites, for example, or by converting a section of regular seats into club seats. In others, it requires an entirely new skin to be erected around a stadium's exterior.

Michigan Stadium's classic, no-frills aesthetic has survived seven renovations since the bowl opened in 1927. However, the addition of a proposed 70-plus suites by 2009 will not only drastically change the look and feel of the stadium -- with multistory buildings rising up from behind familiar banks of bleacher seats and blocking out a fair amount of late-afternoon sun -- but also threaten the stadium's bragging rights as the nation's largest at 107,501 seats. That's because driving the premium-seating decision is a desire to widen both aisles and individual seats within the bowl itself, as well as upgrade points of sale and rest rooms. surveyed its fans three years ago and again this summer to get a pulse on their stadium priorities.

"Twenty percent of the sample is very interested in wider seats, wider aisles and fan amenities," says executive associate athletic director Mike Stevenson. "Another group says, 'You can't not be the biggest house.' We have two polarized groups, and our goal is to try to meet both of their concerns."

Moreover, surveys can shape how premium seating areas are ultimately designed and operated. They might show that the politically touchy subject of alcohol availability is important to some prospective buyers, but perhaps not a deal-breaker. Being able to hear the crowd and marching band may be a priority among potential suite lessees, dictating that retractable windows be specified in construction plans. Michigan State officials learned, somewhat surprisingly, that a majority of prospects favored communal suite-level rest rooms over sacrificing individual suite space for private facilities.

Whatever the public whims may be, administrators and architects agree that estimating market demands and expectations should incorporate the work of one or more independent consulting firms, particularly when determining ideal inventory figures. "We ended up using Pricewaterhouse Coopers, and as it turns out their numbers were right on," says Tompkins, adding that Purdue has sold out Ross-Ade's 34 suites and 200 indoor club seats. "In my opinion, you'd like to have a little bit of a waiting list. It's hard to leave money on the table, but it creates a sense of urgency among existing buyers."

Perhaps no school has witnessed that sense of urgency more than the University of Arkansas, where waiting lists exist for suites in the school's football, basketball and baseball venues. The Arkansas football program, in particular, has proven the overwhelming popularity of premium seating in Fayetteville. A 2001 renovation of Razorback Stadium had originally sought to increase the number of suites from 43 to 102, but a fast-growing waiting list quickly rendered those seemingly ambitious plans obsolete. Instead, a stunning 132 suites were specified for the $115 million stadium overhaul, which also included vast infrastructure improvements and the introduction of a combined 9,028 indoor and outdoor club seats.

According to Jim Gray, the university's associate athletic director who oversaw the expansion, only six stadiums in the country offer more suite inventory than Razorback Stadium, and those venues serve professional franchises. Still, one could argue that despite the mid-renovation adjustments, Arkansas still underestimated market demand. "We never even marketed the suites," Gray says. "Right now we have 30 or 40 names on a waiting list, and we probably could fill more suites than that if we had them. In fact, we've talked about adding some 30 to 60 more."

Even if Arkansas is currently leaving some revenue on the table, it's pocketing plenty, too. Prior to renovation, a full house of 51,000 fans at Razorback Stadium brought in $800,000. By comparison, Southeastern Conference rival Tennessee's take for sold-out home games at 104,000-seat Neyland Stadium was closer to $3 million. "There was quite a disparity, and we were trying to keep up," Gray says. "We had to figure out a way to raise revenue. We're not going to sell 100,000 seats, so we went with the premium-ticket method."

Last season, with all 132 suites occupied by 12, 15, 18 or 24 fans and more than 8,000 club seats sold, Arkansas realized average per-game revenues of $2.8 million -- a figure that more than justifies the renovation, according to Gray. "That's the reason we did it," he says.

It's clear that premium seating holds great income potential from an institutional standpoint. But what impact, if any, might it have on the financial landscape of college football in general?

Capital improvement expenditures among NCAA-member schools have never been tracked by the association through its biennial reports, "Revenues and Expenses of Intercollegiate Athletics Programs," mainly because -- like coaches' compensation packages -- the money trail can be hard to follow when relying on current survey forms and the individuals who fill them out. However, a partnership between the NCAA and the National Association of College and University Business Officers, instituted last year, has sought improved methods of collecting accurate data regarding capital expenditures and debt service, as well as coaches' compensation packages.

For now, this much is clear to Dan Fulks, the Transylvania University accounting professor who has authored the NCAA's revenues and expenses reports since 1991: The revenue gap is widening between Division I-A's elite schools and those Fulks refers to as "the pretenders."

"My data show that in Division I-A, 47 schools -- or 40 percent of the total 117 -- show a profit, and that profit on average is $5 million a year. The other 60 percent are losing about $4.5 million," Fulks says. "And what's happening is the profitable schools are making more and more money, and the losers are losing more and more. So the gap between the haves and the have-nots is getting wider and wider."

It's a situation exacerbated by the premium-seat-driven stadium expansions witnessed over the past 10 years. In 2001, the year Ohio Stadium unveiled a $194 million renovation featuring 81 suites and 2,600 outdoor club seats, the football program alone generated $47 million in revenue. The average revenue generated by entire Division I-A athletic departments that year was $25.1 million. Last season, premium seats accommodating fewer than 3,500 fans at 101,568-seat Ohio Stadium generated $5.7 million over six home games, compared to the $28 million generated by total ticket sales. "We've been fortunate that the revenue streams that we have are basically paying the $14.5 million annually on our stadium renovation bonds," says Pete Hagan, OSU's assistant athletic director for finance. "The project is basically paying for itself."

"The reason that the haves are making more and more money is ticket sales. Ticket sales are by far the number-one revenue producer -- accounting for 27 percent of all revenue in Division I-A," says Fulks. "When I went to school at Tennessee, I bet we didn't have 50,000 seats. Then they added an upper deck on one side. Then they added the upper deck on the other side. Every time they put 10,000 more seats in Neyland Stadium, they sell it out. And then they raise the ticket prices. It doesn't matter. They still sell it out."

Of course, perennial sellouts imply infinite demand. But even schools that regularly fall well short of selling out their football venues are taking the premium-seating plunge. Indiana University, which hasn't won more than three football games in any of the past three seasons, drew an average home crowd of 28,000 to 52,000-seat Memorial Stadium in 2004. Yet, sales of the stadium's 300 indoor club seats keep chugging along -- from roughly half sold in their debut year of 2003 to 178 last season to 230 as of this writing. "I think a lot has to do with the positive enthusiasm and energy right now surrounding our new football coach," says Kelly Bomba, associate director of IU's Varsity Club, referring to first-year coach and Indiana native Terry Hoeppner. "That, plus a hard-working sales force."

The University of Illinois welcomes a new football coach into the fold this fall, as well, while officials there tentatively plan to add 49 suites, 200 indoor club seats and 1,200 outdoor club seats to 71,000-seat Memorial Stadium by 2008. There appears to be little concern over the fact that the Illini, who won the Big Ten football title as recently as 2001, played in front of 20,000 empty seats, on average, per game last season. "I think the biggest concern was not doing it and getting further behind the schools that have already taken on such projects," says Illinois associate sports information director Cassie Arner. "Even though we may not be selling out right now, we're very optimistic that our program is on the rise and that this will only help our attendance figures. It's just another way that we feel we can make the game experience better for our fans and for our donors."

But with new coaching eras often come short grace periods, and some believe the same may hold true for premium seating. "There's sort of a honeymoon period that comes with suites, especially for stadiums at colleges and universities that have never had them," says Randy Bredar, director of sports architecture at HNTB Sports Architecture in Kansas City, Mo. "There's that initial demand because when they're brand new, they're the sexy new toy to have. What will the renewal rate look like after the honeymoon is over and the luster of this brand new thing is, perhaps, gone?" most cases, the product on the field has to keep shining, too, according to Dick Sherwood, president of the Philadelphia-based consultancy Front Row Marketing Services. "Whether it's at the college level or the professional level, winning makes a difference," he says. "It makes everything easier to sell."

It's too soon to forecast repeat sales success among many schools that have locked their suite-holders into five-, seven- and even 10-year lease agreements, since their renewal efforts haven't yet begun in earnest. Some schools, including Purdue and Penn State (which still has a full quarter of its club seat inventory available after a 2001 renovation of Beaver Stadium), even ask for multiyear commitments from their club-seat holders. "Schools that are historically sold out and have waiting lists can do it on a year-to-year basis because the renewal is a given, it's automatic, and it's just a matter of cranking out the paperwork and changing the dates," Tompkins says. "If you're a school like ours that is not guaranteed to be sold out, you don't want to be reselling that seat every single year."

The initial sale often proves to be the toughest, Tompkins adds. "We started marketing all of the inventory before we ever put a shovel in the ground," he says. "One of the challenges is trying to sell something that you've never had before. Until fans really experience it, they're just looking at brochures, and they don't totally get it. Once the 2002 season started and the place opened, people were like, 'Oh, this is what it's all about.' By the end of the season, we had sold the remaining 50 of our 200 indoor club seats."

Knuth is counting on similar developments at Michigan State, which didn't sell out the premium seating in its hockey venue until the second season it was available. Same goes for the Spartan Club -- the 10 rows of chair-back seats between the 20-yard lines offering fans in-seat service and priority parking -- that was added to the football ticket mix in 1994.

If all premium seating in Spartan Stadium is sold out by season three, the athletic department will begin netting more than $1 million annually, according to Knuth. "That's a pretty substantial number when you're talking about the cost of student-athlete scholarships in 25 varsity sports," he says. "It's revenue that we have to have, so it's important for our fans to support this project."