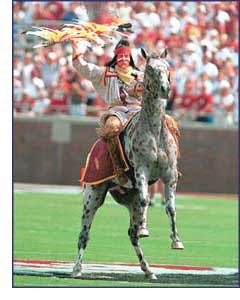

Photo of FSU's Seminole mascot

Photo of FSU's Seminole mascot

He had been invited there to witness another first: The five-member council voted unanimously to adopt a resolution and "go on record that it has not opposed and, in fact, supports the continued use of the name 'Seminole' and any associated head logo as currently endorsed by Florida State University." While the action represented the first time since 1947 -- when the university began using the tribal name -- that the relationship had been formally spelled out, there always existed what FSU spokesperson Frank Murphy calls an "unwritten understanding of cooperation."

That cooperation resulted in the university retiring its Sammy Seminole caricature in the 1970s and evolved to include the launch of Seminole Scholars -- a program that in its first three years has provided FSU educations to 10 members of a tribe in which roughly 4 percent of 1,500 adults hold college degrees. It has also long meant participation by Seminole people in university commencement and athletic events. "These are not things that we are just starting now," Murphy says. "But there are new opportunities. The tribe is certainly more successful economically than it has been in the past two decades, and it is launching programs that we can help with."

In the near future, Florida State intends to lend expertise to the development of a charter school on the tribe's New Brighton Reservation. A new teaching branch of FSU's medical school will soon be located in Immokalee, where residents of the tribe's Immokalee Reservation stand to benefit from improved health care. Back on FSU's Tallahassee campus, a center for Seminole heritage and culture is in the works.

Perhaps all of this will go unnoticed by the average fan who sees only a spear decal on the side of a football helmet and a pregame ritual involving a horse. "Some of the prominence that Florida State University has enjoyed nationwide comes through its football program's exposure on television," Murphy admits. "But the Seminole tribe in this resolution made it very clear that it's happy with the use of the name. The name is revered here, because the Seminoles were the unconquered people. They would not be driven out of Florida. They never lost the Seminole Wars, and no one ever declared victory."

Just who, if anyone, declares victory this month, when the NCAA's Subcommittee on Gender and Diversity Issues mulls the fate of American Indian mascots, is anybody's guess. The decades-old debate gained new momentum last November, when the NCAA's Minority Opportunities and Interests Committee requested self-evaluations of the 33 schools using American Indian nicknames at the time. Most of those evaluations were received by the May 1 deadline (one school is still in the midst of an extension, and three others changed their names voluntarily), with MOIC recommendations to be discussed Aug. 3 by the aforementioned subcommittee. If deemed necessary, the subcommittee will forward its own recommendations to the Executive Committee, which meets the following day, with an official NCAA position on the issue possible soon after.

The NCAA could declare outright prohibition -- an outcome Corey Jackson, staff liaison to the MOIC, calls "possible, but not probable" -- or it could adhere to the longstanding status quo. A 2002 MOIC report, culminating 18 months of study, stated, "While the committee feels that it is time for this tradition to be retired, it acknowledges and supports a member institution's self-determination on this issue."

"So far, the issue has been left up to schools, but the NCAA has a vested interest in this issue based on our constitution and what members have agreed upon with regard to diversity, discrimination and ethical conduct in collegiate athletics," Jackson says. "We are a membership-driven organization, but we also want to be sensitive to the student-body members out there who don't participate in athletics."

The NCAA has arguably effected change inside and outside its own membership by merely revisiting the issue over the past year. Stonehill College, one of the three schools to voluntarily make a moniker switch, used an online poll to select a replacement name for "Chieftains," and as of July 1 became the "Skyhawks." In May, Indiana Tech, a member of the National Association of Intercollegiate Athletics, tweaked its Warrior mascot to resemble a shield-toting Roman, not the weapon-wielding Indian of the past.

More high schools, too, are erring on the side of sensitivity these days. In the past six months alone, the Lemont (Ill.) Injuns became the Titans, the Rhinebeck (N.Y.) Indians became the Hawks, and the Marshall (Mich.) Redskins became the Redhawks. J.F. Webb High School in Oxford, N.C., retained its "Warriors" nickname, but retired its American Indian mascot -- the 11th school to do so since the State Board of Education approved a resolution in 2002 discouraging their use. In June, the Democratic majority on California's Senate Education Committee pushed through a bill that would ban the use of "Redskins" among public schools in the state, while in Wisconsin, members of the Northwoods Republican Party passed a resolution asking all public schools in that state to consider retiring all American Indian nicknames.

Meanwhile, separate public-opinion polls conducted within the past four years suggest little moral handwringing over American Indian mascots -- even among American Indians. When the Peter Harris Research Group asked 352 American Indians whether high school and college teams should stop using Indian nicknames, 81 percent said no, according to Sports Illustrated, which published the results in March 2002. Nearly seven in 10 American Indians polled didn't even object to the name "Redskins." In September 2004, the University of Pennsylvania's National Anneberg Election Survey found 90 percent tolerance for "Redskins" among an American Indian sample more than twice the size of the Harris poll.

Of the 29 remaining schools targeted for self-evaluation by the NCAA, none use "Redskins." Seven borrow specific tribal names, seven use "Indians," six apiece use "Braves" and "Warriors," and one each uses "Redmen," "Savages" and "Tribe."

On their face, some appear easier to defend than others, but one wouldn't know it by reading the self-evaluation of Southeastern Oklahoma State University, located two hours' drive from the very spot marking the end of the Trail of Tears. "Being a Savage denotes a love for the game, enthusiasm, discipline, honesty, appreciation, striving, and the attitude of becoming a victor," states the school's self-evaluation. "Our conclusion is that Southeastern's nickname is associated with Native Americans only in the minds of individuals or groups who do not comprehend the connotation embraced by athletes at the university."

State Sen. Judy Eason McIntyre is one such individual. In February, the Tulsa Democrat introduced the Oklahoma Racial Mascots Act, which specifically sought to prohibit the use of "Savages" and "Redskins" as nicknames among state schools. The bill, which had the support of the Tulsa Indian Coalition Against Racism, died in committee.

Count the Inter-Tribal Council of the Five Civilized Tribes, based in Tahlequah, Okla., among the groups that can't comprehend the "love" and "enthusiasm" connotations of "Savages," or any other American Indian nickname, for that matter. In July 2001, the council -- representing the more than 400,000 members of the Chickasaw, Creek, Cherokee, Choctaw and Seminole (not to be confused with the Seminole Tribe of Florida) nations -- drafted a resolution calling for the elimination of such "offensive" and "disgusting" names.

Max Oseola Jr. is one American Indian insulted by "Redskins," "Savages" and names like them. But as a councilman for the Seminole Tribe of Florida, he hopes the NCAA ultimately respects the sovereignty of his and other native peoples. Nearly a quarter of 11,200 respondents to a USA Today online poll agree, stating that the NCAA shouldn't ban American Indian nicknames, but that tribe approval should be required. "The NCAA should tell institutions to go to the tribes that they're depicting and get their opinion," Osceola Jr. says. "We made our decision based on a relationship between one tribe and one university, but if another tribe wanted to sever its relationship with a college or university, I would support that also."