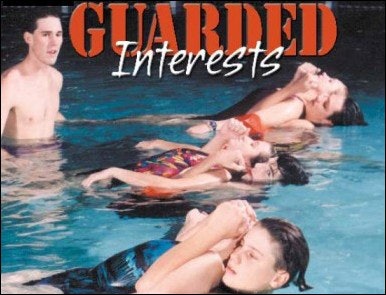

Retaining young lifeguards requires creativity in the ongoing training process

WANTED: Part-time summer help. Must be at least 15 years old and prepared to face life-or-death situations daily. Will train. $6/hour.

There's a shortage of lifeguards in America, and it's little wonder why. The job of patrolling recreational aquatic facilities can be at once stressful and dull, and the task of finding able bodies willing to accept the whistle and ascend the chair challenges pool managers nationwide. And while recruitment is one issue, retention of lifeguards - many of whom are teenagers in search of summertime fun money - can be equally burdensome. Keeping young lifeguards motivated, effective and in the fold often comes down to training techniques, and aquatics experts agree that a little creativity goes a long way.

"You're dealing with something as complex as lifeguarding, and you're dealing typically with young kids who have no prior experience in the workplace," says Jill White, executive director of Starfish Aquatics, a Savannah, Ga.-based lifeguard training agency. "You're dealing with work conditions that, on one hand, are very stimulating and exciting and yet, on the other hand, are very demanding physically. When working with young people especially, the more creative you can be and the more you can get them involved in the training process, the more they're going to want to participate."

Gone are the days of herding a group of would-be lifeguards into a classroom for training lectures, according to Shawn DeRosa, aquatics program coordinator for the Commonwealth of Massachusetts. "The challenge that we're facing is that the youths of today are more accustomed to interactive learning - to videos, to computer technologies, to graphics, to colors," says DeRosa, who recently helped rewrite the lifeguard training curriculum for the American Red Cross. "In the new Red Cross lifeguarding program, we're seeing lifeguard-specific scenarios and scenario-based training - pictures of lifeguards in action and much more excitement in the videos. There's increased interaction in the classes. We've removed a lot of the lecture format and incorporated more discussion to try to keep these kids interested and engaged in the learning process."

But aquatic managers, take note: Regardless of what certification agency is used - be it the Red Cross, Jeff Ellis & Associates or the YMCA - lifeguards are likely to get more out of the training they receive post-certification. That's one of the findings of "The International Lifeguard Rescue and Resuscitation Survey," released last year by researchers at Penn State and East Carolina Universities and the University of Maryland. Of 2,082 lifeguards surveyed from the United States, Canada, Australia and New Zealand, nearly two-thirds believed that on-the-job training proved better than training received during their certification course. The message of Tom Griffiths, director of aquatics at Penn State and the survey's lead author, seems clear: "Make training as applicable as can be to the real setting."

So what is the real setting? Despite the proliferation of interactive water parks over the past 15 years, the vast majority of recreational aquatic destinations remain traditional rectangular lap pools. Oklahoma City Community College's two indoor pools, for example, are used to train roughly half of the 500 lifeguards that serve the metropolitan area's one million residents. Even though those lifeguards may feel well-prepared to establish themselves in their given workplaces, Chris Moler, the college's director of recreation and community services, advises aquatic managers to take three steps in preparing lifeguards for duty once they arrive at their new place of employment.

First, all prospective hires should be prescreened. "If you're a good aquatic manager, you pretest lifeguards," Moler says, adding that card-carrying lifeguards may be years removed from any actual training or employment. "In addition to the interview and background check, you should physically get them in the water, run them through a series of basic critical skills that a lifeguard is supposed to know and test them."

Once hired, all lifeguards should experience preseason training that pays attention to the facility's own configurations, protocols and supplies. Moler uses spinal injuries as a prime example of how procedures may be dictated by a given facility. "The rescue board is probably one of the more critical things that lifeguards need to be concerned about, because each facility is different and has different gutters and different decks and different boards," he says. "The amount of time spent on spinal injuries in all lifeguard training classes is pretty good, but more often than not most lifeguards are trained in some other facility on some other board, and the techniques are not what you would call real clear. Consequently, there's a need for that individualized training in the facility where they actually are going to work."

DeRosa provides another example: those pools, typically built during the 1960s, that feature a surrounding 1-foot wall, which not only requires swimmers to take a step up to enter the water, it forces lifeguards to reconsider their approach to rescue. "That alters how you extract a victim from the water," DeRosa says. "You can't do it the same way that we've traditionally taught you to do it in your lifeguarding course. So you need to learn how to modify the skills that you've learned in class to meet the requirements of your facilities."

Finally, the accepted industry standard of care dictates that a minimum of four hours of in-service training be conducted each month. At Oklahoma City Community College, topics may include everything from internal communication problems to customer-service tips. "Then we'll also focus on one major critical skill that everybody's going to work on to try to bring it up to speed," Moler says. "At one in-service training, we may spend an hour or two on spinal injury. At the next one, we might work on CPR. At another, we might review bloodborne pathogens."

Along with varying the subject matter of training sessions, aquatic managers might consider delivering the material in creative ways. White, for one, has used the popular game show formats of "Who Wants to Be a Millionaire." and "Jeopardy!" to challenge lifeguards' knowledge levels. "We do a 'Monopoly' game that's designed with our aquatics facility in mind," she notes. "Rather than properties, it's different areas of the pool, and they have to perform certain skills or answer certain questions as they continue around."

Moler may have his lifeguards join hands and tie themselves into a human knot, then untie themselves, as one team-building exercise. Another may involve the swimming of relays. Guards also are allowed to display their skills individually during a training event called "The Beast," in which participants swim a different stroke in each of three 25-yard lengths before running stairs and jumping off a diving tower. "They keep times, so it's a conditioning activity," Moler says, "but there's also some real pride in getting a good time or even being the best."

Even as aquatic managers strive to make training more effective and fun, the one message that must come through is that lifeguarding is serious business. "Our biggest challenge as a training agency is to be able to make the guards understand that this is like no job they may ever have - being responsible for people's lives," White says.

"We try to promote the fact that this could be the hardest job they've ever had," says Moler. "Where else can you be 16-years-old and get the necessary training to be a professional rescuer and be held accountable in a court of law if somebody dies on your shift? There's no other job in the world that will take a 16-year-old and give him or her that kind of responsibility."

As a result, professionalism is paramount, and public relations skills should be part of any facility's lifeguard training. In fact, a lifeguard's public relations skills are far more likely to be tested daily on the job than his or her rescue skills. Arriving late, leaving water unattended while talking to patrons and flirting with other guards are all habits that cannot be tolerated in the aquatic setting, Moler says.

As part of its in-service training, Oklahoma City Community College sometimes incorporates role-playing exercises to emphasize the importance of professionalism. One lifeguard assumes the role of head lifeguard, while another plays the aquatic manager. Meanwhile, the real head lifeguard and aquatic manager become "regular" lifeguards. "They come in late and make excuses and mock some of the things they have witnessed the guards do on the stand: leaning way back and acting disinterested," explains Moler. "And now the lifeguard, who's in the role of the higher-up manager, has to react to that. They have to explain to them why they shouldn't do this.

"It really serves several purposes: The lifeguards have to, number one, put themselves in the manager's shoes; number two, witness what that behavior can look like; and number three, go through the steps of disciplining that employee. It makes both groups a little bit more sensitive to what the other has to go through."

Other forms of role playing also sensitize lifeguards to the types of patrons they may encounter at the aquatic facility. During training sessions, Moler's lifeguards may be asked to stuff cotton balls in their mouths to simulate a speech impediment or tissue in their ears to simulate hearing loss. A guard might don eyeglasses smeared with Vaseline to experience what it's like to have impaired vision. Pillows stuffed under a T-shirt show lifeguards how getting out of the water can be more difficult for some patrons than others. "It creates sensitivity for some of our users' needs," Moler says. "That's been helpful in getting lifeguards to understand how to slow down their speech and how to be more clear. We try to focus on customer service a lot."

This type of sensitivity training can prove every bit as challenging as technical rescue skills when teenage employees are involved, Moler admits. "They like the rescue skills. They think it's cool that they can do them. That's a challenge, and they practice, practice, practice that," he says. "The biggest challenge that most aquatic managers face is not the skills. It's the attitudes and the behaviors."

"Given the nature of employing today's teenagers, we often have to start off with basic job skills and uniform policies - reporting to work on time - and incorporate that into our own training for these lifeguards at our facilities," says DeRosa. "Customer service is probably the number-one role of the lifeguard."

Most kids are bright enough to realize that what they've seen transpire on the fictitious beaches of "Baywatch" is not what they're likely to experience at their real-life community pool. But few may be fully prepared for a job heavy on customer service and light on lifesaving. Unless he or she is employed at a well-trafficked water park, the typical lifeguard may log thousands of hours on duty before being called upon to perform a rescue or even assist in one. For that reason, a large part of the lifeguard's job is staying alert while combating boredom.

"Many guards have the perception that they're there just to wait until something happens, almost like a fireman, and then they react," says White. "They don't realize that the minute they get into the zone for which they're responsible, it's got to be 100 percent attention 100 percent of the time."

"Having lifeguarded many times, I can say that you do get myopia," DeRosa says. "You just stare into the water, and oftentimes you appear as though you're watching the water but, in effect, you're not there - you're thinking about something different."

Based on his research, Penn State's Griffiths has helped develop a technique that seeks to relieve onthe-job boredom and cure zombie-like lifeguards. The "5-Minute Scanning Strategy" dictates that each lifeguard significantly change his or her posture or physical position every five minutes while maintaining constant surveillance of the water. If a lifeguard has been sitting for five minutes, he or she should stand for the next five, then roam the pool deck during the five minutes after that. "We spoke to psychologists, military personnel and ophthalmologists, but the 5-Minute Scan is based, first of all, upon information from the guards," Griffiths says. "We asked, 'How do you stay alert? How do you remain vigilant while on duty?' And literally hundreds of people found that the number-one way was a variety of physical activities such as walking and standing and roving and talking." Such a believer in the power of these posture changes is Griffiths that he has even developed an alternative lifeguard station to the traditional tower stand (see "Help Is on the Way," p. 74).

Griffiths and others also advocate regularly rotating on-duty lifeguards, so that each guard changes stations every 20 minutes or so. Says White, "Any time you make any type of change in location and a shift in focus, it helps. You run into trouble when a guard is stuck in the same position for hours on end."

The definition of lifeguarding is constantly changing, too, and those entrusted with the training of lifeguards need to embrace the job's expanding responsibilities. "Over the years, the terms 'lifeguarding' and 'lifesaving' have, at least in the minds of the general public, been synonymous," White says. "The technology and responsibilities have really changed to where, now, when you use the term 'lifeguard,' it is very specific and means that someone is providing a certain standard of care. Usually that standard of care revolves around surveillance, with the idea that a lifeguard can catch something happening very early and keep it from becoming catastrophic."

The technology has evolved to supply lifeguards with equipment that not only helps save the lives of pool patrons in trouble, but also protects the lifeguards themselves. For example, the rescue tube, a buoyant length of highdensity foam that is carried and controlled with the use of an attached lanyard, allows guards to extend flotation assistance to victims while using the tube as a sort of buffer. With the tube between the two individuals at all times, lifeguards can distance themselves quickly, if only temporarily, from a panic-stricken victim who may otherwise try to keep his or head above water by pulling the lifeguard under. All the while, the lifeguard maintains control of the rescue tube with the lanyard until the victim settles down.

"I think we're experiencing a shift in expectations for lifeguards," says DeRosa. "In the past, we expected lifeguards to go in and save lives. Now, we're focusing more on injury prevention, and from an employer perspective, we're focusing on employee protection. We've seen a shift from non-equipment-based rescues to exclusive training in equipment-based rescues."

That shift in expectations makes ongoing lifeguard training all the more critical. "I think many employers are still under the incorrect assumption that lifeguards coming in are ready to go to work when, in fact, they're not. They have the basics; they need to learn specifics," DeRosa says. "At a bare minimum, lifeguards must be trained in the emergency action plan or plans at their facility. Also, at a bare minimum, they need to be trained in the use of any special equipment used at their facility. If they're aware of the plan and the equipment, they're off to a good start."