Enabled by a generous gift from the late wife of the founder of McDonald's, The Salvation Army is planning community recreation centers for underserved populations worldwide.

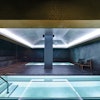

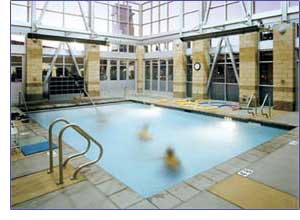

The aquatic center at the San Diego Kroc Center

The aquatic center at the San Diego Kroc Center

If only that vision had been ultimately realized for the families of this South Side community. In essence, replacing one "Black Belt" ghetto (the former "Federal Street Slum") with another, the Robert Taylor project at its prime -- if it's even appropriate to use such a word -- housed 27,000 low-income, African-American residents. By its silver anniversary, the poorly managed housing project had become synonymous with the worst aspects of Northern urban cities: poverty, blight, crime, violence and segregation.

Today, only two towers remain standing (wrecking balls razed much of the Robert Taylor complex between 2000 and 2004), and there are visible efforts to erase from the national conscience that symbol of urban despair. In its place, officials with the city of Chicago and The Salvation Army intend to erect a much more positive symbol -- one of hope, opportunity and, you guessed it, salvation.

Much of the 95-acre site formerly occupied by the Robert Taylor Homes is being redeveloped, as is the entire Chicago Housing Authority inventory, into new mixed-income housing units as part of the authority's 10-year, $1.6 billion Plan for Transformation. But 25 acres have been earmarked for a future Ray and Joan Kroc Corps Community Center, to be owned and operated by The Salvation Army. (A corps is a church, in Salvation Army speak.) It's expected that the community recreation facility will be one of as many as three dozen built nationwide over the next few years, thanks to a bequest of more than $1.5 billion from the late McDonald's heiress, Joan Kroc.

A lifelong supporter of The Salvation Army, Kroc gave $92 million to the organization in 1998 for the construction and operation of the first Kroc Center in her hometown of San Diego. That 190,000-square-foot complex, which opened in June 2002, features an outdoor aquatic center, an ice arena, a gymnasium, athletic fields, a family enhancement center, a 600-seat performing arts theater, an arts and education center, and a traditional Salvation Army chapel. At its dedication, Kroc described the San Diego center as being more than just a recreation center; she saw it as a "miniature peace center," a place where "children will learn of each other."

But Salvation Army officials are aware that sports and recreation remain vital tools through which they can reach their intended audience, youths and their families. Such tools support what Maj. Ralph Bukiewicz, the Central Territory's head of community relations and development/Kroc Center coordinator, calls The Salvation Army's "holistic approach to developing mind, body, soul and spirit."

Given the early success of the San Diego Kroc Center -- which, according to facility administrator Maj. Cindy Foley, has 4,500 members, averages 2,300 daily visits and has served more than 800,000 people since opening three years ago -- that approach seems to be right on target. In fact, Kroc was so encouraged by her first facility's achievements that shortly before her death from inoperable brain cancer in October 2003, she arranged for the unprecedented gift from her estate so The Salvation Army could build many more community centers.

"It was rather stunning, to say the least, when the corporate trustees of the estate called and told us the number," says Maj. George Hood, The Salvation Army's national community relations secretary. "We were all sitting here wondering, 'Did we hear him right?' "

Once Salvation Army officials had a chance to let the magnitude of the donation sink in, the terms of the bequest were made explicit: The money was to be handed over to The Salvation Army's national headquarters and immediately distributed in equal portions to the Army's four United States territories, each of which are corporations independent of the national headquarters. Each territory was then allowed to determine by its own methods how many and which communities within its boundaries would receive a grant. Of each grant, half of the money would go toward facility construction and development. The other half would be reserved in an endowment from which the interest would be used to indefinitely sustain that facility's operations. Kroc specified that none of her donation could be used for existing programs, services and administrative costs.

In keeping with Kroc's vision that the community centers bearing her family's name serve traditionally underserved populations, the majority of them are being targeted for urban, low-income neighborhoods like Chicago's South Side. Early needs assessments of that community reported three major deficiencies: job availability, assistance and training; safe places for recreation; and social reintegration assistance for those coming out of the corrections system.

"We have some people who fall into one of those three categories, and some families fall into all of them," says Maj. David Harvey, administrator of the Chicago Ray and Joan Kroc Corps Community Center Project Development Office. "But I hear from people in the community that they don't want just another social services center. Food pantries, emergency housing and day-care centers help support a family, but they don't always point a family in the right direction. Mrs. Kroc was adamant that this be a place that uses recreation and the arts to give people hope and a desire to advance in the world and discover their gifts."

Much has to happen before Kroc's dream becomes reality. By Oct. 27, a jury made up of architectural advisers and Salvation Army officials from the Central Territory's Metropolitan Division -- which encompasses all of the Chicagoland area, northern Illinois and northwestern Indiana -- must select a winning proposal for the Chicago Kroc Center from among those submitted by four design teams (a public design competition began July 1).

And though the development of the Chicago project is for all intents and purposes well under way, it has yet to be officially green-lighted by Central territorial staff. In fact, it is one of 10 projects selected to advance to the second of a three-phase development process; the other nine Central Territory finalist communities are Aurora, Ill.; Detroit; Duluth, Minn.; Grand Rapids, Mich.; Green Bay, Wis.; Omaha, Neb.; Quincy, Ill.; St. Joseph County, Ind.; and St. Paul, Minn. This three-stage process began in February, with 39 communities from 11 states submitting preliminary applications for a Kroc grant (stage one). In June, that field was whittled down to 10. By the close of stage two in mid-February 2006, Central Territory officials -- basing their decisions primarily on the design concepts due for each proposed facility by this fall -- hope to have made up their minds on which communities will receive a Kroc grant. Stage three involves the actual construction of the Kroc Centers, and is expected to wrap up by mid-2007.

"We don't so much want the competitive process to pit community against community, as was the case initially in trying to boil down to those 10 finalists," says Bukiewicz. "We now want each community to be competitive against its own standards, its own expectations and its own vision. That's why we want to be as helpful and supportive as we can. I'd like to believe that all 10 will end up with a Kroc Center."

Though ultimately it's up to the discretion of each Salvation Army territorial staff to administer Kroc Center development within its boundaries, the four entities have corresponded regularly regarding their respective programs. As it happens, three of the four territories -- the Western, Central and Eastern -- are subscribing to a very similar development process. (On the contrary, the Southern Territory is approving projects through a rolling selection process, and as of August had green-lighted six Kroc Centers.)

The Salvation Army has great expectations of its project submitters. The four guiding principles set for finalists in the Central Territory are typical of what is expected from design proposals nationwide.

First, the proposed facility must effectively accomplish the mission and ministry of The Salvation Army, in concert with Kroc's aim to expand arts and recreation opportunities for disadvantaged communities. "We want each potential facility to be able to touch on not only the recreational, athletic and physical development aspects, but also that family enrichment element -- the worship and Christian activity," says Bukiewicz. "Because even though this is not going to be a facility that in order to participate you have to be a member of the Salvation Army, The Salvation Army is first and foremost a church."

In addition, each facility must be designed for financial viability. This mandate has been largely influenced by the lesson learned by San Diego's Foley and her staff. It was originally intended for the San Diego Kroc Center to be built on a $40 million construction budget, with another $40 million going into an operations endowment. But construction went $17 million over budget, and although Kroc still provided roughly $40 million for an endowment, Foley admits that her facility's "financial challenge will always be a little bit greater" than that of her soon-to-be fellow facility operators.

Of the San Diego Kroc Center's $6 million annual operating budget, Foley can only rely on $1.8 million in endowment funds; the facility must generate the remaining $4.2 million through program and membership fees. Sure, a shrewd business plan has helped the San Diego Kroc Center balance its budget, but Foley says that given her facility's experiences, "what everyone else realizes is that in order to achieve our mission and help the most people possible, equal endowment to equal construction is not ideal. You really need a larger endowment."

That said, territorial leaders have challenged each submitting community to expand its endowment, through fundraising, by an additional 50 percent. "Since we are a nonprofit organization and we want this to be an affordable facility, especially for those who are underserved, we have to get very creative about where the funds are going to come from," says Bukiewicz.

While fiscal conservatism governs decisions regarding planned operations budgets, Salvation Army officials acknowledge their preference for attractive facilities -- or in Bukiewicz's words, those with "optimal architectural design and high-quality construction." Again, it's what Kroc would have wanted. "According to Joan, they should be of the highest caliber," says Bukiewicz. "She didn't believe in cutting corners, in skimping on costs. Yet within The Salvation Army, we need to find a balance between that and the sense of excellence that we want within our facility."

Each Kroc Center is also expected to collaborate with existing organizations in its community, whether those agencies provide child-care or fitness programs. This is one way The Salvation Army intends to sidestep the unfair competition issue. "I understand private corporations are quite concerned with what has happened with other groups that have had recreation centers," says Lt. Col. Don McDougald, assistant to the chief secretary of the Western Territory, which has selected eight finalist communities. "We're trying to be sensitive to that and not be in competition with them. We'd rather be partners."

Bukiewicz agrees, but adds one caveat. "There's a fine line between collaborating and partnering. Joan Kroc demanded these facilities be owned and operated by The Salvation Army. So it's not as if there are going to be a number of other agencies or facilities nested within these compounds. Rather, we're finding ways to work cooperatively."

In San Diego, this has meant opening up the aquatic center's 25-meter competition pool to swim and water polo teams representing area schools, including San Diego State University, which does not have an on-campus aquatic facility. "Their rental use of the pool at off-peak times helps us make it available to neighborhood children at peak hours," says Foley.

For her part, Foley doesn't mind deferring to San Diego's best and brightest, as long as doing so opens doors for members of her community. "The Salvation Army doesn't have to be the expert on everything," she says. "Because of our name, when we call the San Diego Symphony and say, 'Can we collaborate on a program?', they answer. The symphony comes every month to the center and does free family nights."

In south Chicago, Harvey expects such collaborations to involve local churches and schools (the building site is located directly across the street from Jean Baptiste Point DuSable High School). "I hope we can brainstorm and empower that school to tell us, 'You have half of our kids in your Kroc Center. Here's what we need these kids to do. They're failing chemistry and math. They're going to need those for the future,' " says Harvey. "We can use our sports teams and clubs to motivate kids to do better in school. Just like a coach at school would say, 'You don't have a C? You're off the team,' we can do the same thing in intramural sports."

Of course, Harvey and his staff are faced with the challenge of tracking down those youths and families that once populated Robert Taylor Homes. According to a CHA-commissioned report authored by a former Cook County public defender and released in July at the midpoint of the authority's Plan for Transformation, most of the former residents of CHA public housing -- including those who lived in the Robert Taylor projects -- can't be found. Subjected to a complicated relocation program during housing rehabilitation, all CHA tenants have had to move at least once, with the majority of them moving multiple times. "The CHA appears to have contact information which is often outdated," read a draft version of the audit obtained by the Chicago Tribune. "CHA needs to work on tracking residents more closely in order to ensure that the move-in process is not delayed."

Compounding the problem is the fact that there are no assurances -- actually, it's a numerical impossibility -- that most former Robert Taylor residents will move back into the neighborhood. The 4,400 low-income apartments once housed at the Robert Taylor complex are being replaced by roughly 2,600 mixed-income residences, only a third of which are reserved for low-income families. (The development's way was paved, in large part, by a 1995 act of Congress repealing a 58-year-old federal law mandating that each demolished unit of public housing be replaced.)

The good news is that an academic study published last November by a Columbia University sociologist found that 54 percent of former CHA project residents visit their old communities at least once a week to check in with friends and family members.

Harvey knows that during those visits, he has the best opportunity to connect with and invite Robert Taylor's former residents to a facility that he hopes will help them rekindle and strengthen those life-sustaining social networks -- and develop new sources of inspiration.

"If I want to give someone a job, I can teach him to flip the hamburger, how to push the right buttons on a cash register. But you can't teach him attitude, you can't teach him integrity -- that's all inside," says Harvey. "That's something that athletics and the arts can give people so that when they go out looking for a job, they're more marketable. When they realize what they have to offer, they'll get that job. Not only will they get it, they'll keep it. And these people will know that they didn't get that motivation on the streets -- they got that from the basketball court at the Kroc Center."