New Indoor Facility Hybrids Cater to the Needs of Many Activities

Not so long ago, it seems, a multipurpose facility meant that sometimes the suspended backboards in a gymnasium would be raised to make room for volleyball or badminton matches. Occasionally, hockey goals would be placed on the wooden floor, and folding tables would be turned on their sides and angled in the corners to create a rounded, dasher-board effect.

In recent years, however, college recreation directors and the owners of private sport complexes have broadened the definition of "multipurpose." With the help of innovative architecture and improvements in surface technology, these facilities truly open their doors to as many events as possible - from soccer, lacrosse, tennis and cricket matches to classes, dances, fund-raisers and private birthday parties. The popularity of ice hockey also has sprouted a variety of offshoot activities - in-line hockey, in-line skating and floor hockey - that take full advantage of multipurpose sports areas. Ancillary items such as team benches, penalty boxes, scoring tables and scoreboards, public-address systems, spectator seating and even permanent goals built into dasher systems all serve to make recreational league, club and intramural players feel like they're competing in a varsity or professional facility.

Many new college recreation facilities are built these days with a multipurpose activities court - or a MAC, as they're often referred to in the campus setting. In addition, some estimates place the number of privately operated multipurpose indoor sports facilities in the United States at more than 300, many of which opened for business within the past year. That's a number that doesn't even include family entertainment centers, which take the concept further and come complete with climbing walls, arcades, children's play zones, miniature golf courses, virtual golf machines and other attractions.

As these kinds of spaces continue to broaden (and perhaps even redefine) what a multipurpose facility is, it's worth noting how some colleges, universities and private complexes meet the demands, challenges and ultimate rewards that come with the territory.

Bob England, the recreation/intramural department director at Eastern Michigan University, wasn't searching for rewards or a spot in the history books when he oversaw the 1982 conversion of a wood-floor utility gymnasium at EMU. A space that could keep floor-hockey pucks from sliding underneath the bleachers is all England really wanted. The result? An 80-by-42-foot space with 4-foot-high concrete-block walls, rounded cement corners and a 12-foot-high ceiling.

"I was just solving a problem at the time," says England, who by doing so earned the lasting distinction of being considered the first college and university administrator to introduce multipurpose activities courts to the realm of higher education recreation. "I had the room to do it, and I had plenty of other activities to go in there," England says. "In fact, that gym is still solving my problems."

Indeed, EMU's MAC plays host to intramural and open-gym sessions, aerobics classes, martial arts demonstrations, makeshift concessions areas, casino night fund-raisers and other activities. As part of the 19-year-old, 188,000-squarefoot Olds-Robb Student Recreation/Intramural Complex, the space is now dated, England admits, but it continues to serve its purpose well. "In newer college facilities, the MACs have gotten bigger, the walls have gotten higher, and there's even more room," he says. "I would love to have another crack at designing ours."

Depending on the outcome of EMU's forthcoming recreation master plan, England might just get that opportunity. If he does, he'll no doubt consider some of the current trends in MAC design:

• Dasher-board and glass systems like those used in hockey rinks have become standard in many MACs. If a dasher enclosed MAC is part of a multicourt gymnasium, the dashers and shields usually don't extend much higher than 11 1 / 2 feet, including the standard 3 1 / 2 -foot base and 8 feet of shielding. A suspended divider curtain will provide complete enclosure, similar to how nets separate courts in a gymnasium or field house.

• Line markings for various sports overlap each other in different colors, just as they do in standard gymnasiums, with basketball-court configurations (50 by 84 feet for recreational use; 50 by 94 feet for official NCAA action) serving as a general size guideline. MACs should be designed no smaller than 60 by 14 feet, which allows for 5 feet of clearance on either side of the court and 10 feet of clearance past each baseline. Standard (and unobstructed) ceiling heights run between 23 and 25 feet - much higher than EMU's 12-foot-high MAC, which has seen its share of knocked-out lights from airborne balls, England says.

• MAC surfaces include hardwood, synthetic sheet goods, poured urethane products and suspended interlocking plastic tiles, which are most popular with volleyball players and in-line skaters. While some players might insist on a particular surface for their specific sport, Brad Buchanan, director of recreational sports at Ithaca College, sees no easy solution. "Obviously, you're not going to find any surface that's perfect for all of these activities," says Buchanan, adding that most users understand the compromise they must make to play outdoor sports inside. At Ithaca, for example, a 69by-102-foot space with a rubber surface is set up for specific sports at different times of the day, but no activities are officially programmed. In essence, the room is open for 53 hours of pickup games each week.

• MACs have gotten a lot bigger in recent years, too. A few years ago, a 65-by165-foot facility was considered spacious. Now, the University of California-Santa Barbara is planning a 104-by-185-foot facility that will accommodate three full-size basketball courts.

Ithaca's MAC, housed in the 42,800 square-foot Fitness Center that opened in 1999, doesn't even come close to UCSB's proposed space. But it works well. The MAC is one of two gyms positioned end-to-end in the Fitness Center. It features rounded poured-concrete and cinder-block walls, with rubber flooring for basketball, soccer, tennis, in-line skating, volleyball, floor hockey and other sports. Certain hours of each day are set aside to equip the MAC for a specific sport, and student employees rotate equipment accordingly from a built-in 600-plus-square-foot storage space. Spectators can observe the action in both gyms from balconies.

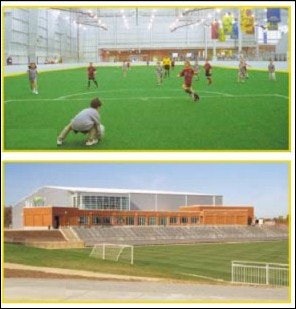

Meanwhile, in a strategy usually reserved for private indoor sports complexes, Ohio State University officials have incorporated two huge indoor synthetic-turf fields with dasher boards into a major recreation renovation and construction project that should be complete by early 2004. OSU's proposed MAC would be one of a handful of collegiate recreation facilities sporting synthetic turf. Its two MAC fields, each covering an estimated 17,000 square feet with a 25-foot overhead clearance, would employ a suspended net system over permanent dasher boards, according to Diane Jensen, the university's associate director of recreational sports. Intended to give the university's outdoor club sports an indoor practice facility, OSU's MAC spaces would offer batting and pitching cages for baseball and fast-pitch softball, as well as accommodations for rugby, soccer, lacrosse, cricket and other sports. There are no plans to install a synthetic surface underneath the turf, Jensen says.

Team bench and spectator areas also are expected to be part of the MAC's design, which would be incorporated into plans for an 80,000-square-foot Recreation and Physical Activity Center located a couple of miles from the heart of OSU's campus, near the university's Fred Beekman Park.

While not a MAC in the strict sense of the term, the University of Houston's Bill Yeoman Fieldhouse sports a 120-yard synthetic-turf practice football field that retracts to reveal an indoor track, four indoor tennis courts, one wood basketball court and a pair of multipurpose synthetic practice courts. Events such as formal balls and the UH Athletics Hall of Honor Gala also are held in the facility, which is part of the UH Athletics/Alumni Center.

That more-bang-for-the-buck mind-set carries over into the private sector, too, where multipurpose sports complexes run a variety of leagues and tournaments by combining the key activities of soccer, field hockey and lacrosse with amenities more common to fitness centers, resorts and restaurants.

"You don't come in here and order popcorn; you order chicken Caesar salad and cappuccino," says Cindy Ross, general manager of the $2.5 million LANCO Fieldhouse, an indoor multisports complex near Lancaster, Pa. The 80,000square-foot facility, co-owned by former indoor National Professional Soccer League player Gary Ross (who's also the resident soccer director), opened in December and houses three washable synthetic turf fields for soccer, lacrosse and field hockey - one measuring 60 by 70 yards that can be divided in half, the other measuring 25 by 50 yards.

The three fields - positioned side by side - have no dasher boards. Instead, white permanent lines are painted on the washable turf. The absence of a wall off which balls can bounce serves as a training method for young players who will eventually take their game outdoors in high school and college competition. "We train our people to keep the ball in play using touch," Cindy Ross says. "When they move outside, they're ready to go. Otherwise, it takes about two weeks to get their touch back."

In addition to a 120-seat food court, the facility offers aerobics classes, training rooms and classrooms, a pro shop and party rooms for rent. College and semi-pro teams work out at the center, which also hosts a variety of weekly soccer tournaments, as well as field hockey and seven-on-seven football tournaments. Some teams travel two hours or more to participate, and LANCO officials are considering implementing daylong or two-day tournaments to draw players from even farther away. The field house can seat up to 700 spectators, and a parking lot holds 240 vehicles. The facility already has played host to more than 5,000 participants and spectators in one weekend.

Each of the four main sports played at LANCO - soccer, lacrosse, field hockey and football - has its own pro in charge of creating programs and running clinics. Originally intended to house only a few sports, the facility already has become a haven for recreation enthusiasts of all sorts, according to Cindy Ross. Ultimate Frisbee teams, local schools' physical education classes, even model-airplane hobbyists rent time at the facility. One patron even comes in during quiet daytime hours, plops his money on the reception desk and punts a football around for an hour. "We've had loads of people give us ideas for using the fields," she says. "It's almost like an airplane hangar in here when all the fields are open."

That inviting indoor environment belies the fact that the exterior of LANCO Fieldhouse - and many of its counterparts in other communities - looks like a warehouse, complete with corrugated aluminum siding. Many such facilities were either warehouses at one time or former big-box retail stores. ("It had to be a big old square thing," Cindy Ross says.) Constructing these monstrous buildings from scratch isn't usually economically feasible - although it worked for the Rosses, who also incorporated a clerestory around the perimeter of the building, positioned just below the roofline, which allows natural light to filter inside.

Once inside these multisport complexes, operators run into constant challenges rotating equipment, maintaining surfaces and marking off boundaries and game lines for various sports. The hours are long, and the competition can be brutal in some markets.

"When we entered the market, there was more competition, but they were run in a mom-and-pop, hodgepodge sort of way, and many of them went under," says John Spanos, a soccer player and vice president of Vetta Sports Clubs, which runs four indoor facilities in the St. Louis area, the first of which opened a dozen years ago. "This is not an easy business. To build from the ground up is very difficult."

That's why all but one of Vetta's facilities are located in renovated clear-span buildings. The cost of the new 44,000square-foot complex - which has two fields and tiered seating for 250 spectators - was more than triple the price of renovating one of Vetta's other three facilities, Spanos says. The only reason Vetta opted for new construction in that case was because no existing buildings at the time matched the company's specs. "Other than that reason, I don't think we'd lean toward building from scratch again," Spanos says.

With two facilities designed as soccer-only complexes that host their own leagues, Vetta also rents one of its facilities to a youth lacrosse league, and another to a youth field hockey league - both of which usually don't occupy the facilities for much more than 10 hours per week. "It's a good way to make some extra revenue, because those leagues will sometimes pay prime-time fees for some not-so-prime-time hours," Spanos says. "And we've seen that the number of lacrosse players is definitely growing. They continually ask for a few more hours a week here and there."

The quality of synthetic turf varies between Vetta facilities, depending on their age, and permanent dasher boards keep the action moving quickly. The only constituency that doesn't prefer the dashers, Spanos says, is lacrosse players. Spanos and his crew allay those players' displeasure by striping lacrosse lines inside the boards, so they don't come into the field of play. Lacrosse enthusiasts, he explains, are willing to give up field size for a dasher-free environment.

Some Vetta clubs also offer facilities for basketball, volleyball, tennis, racquetball, swimming and even batting practice - all of which will help draw more than 1.1 million users into Vetta's four facilities this year.

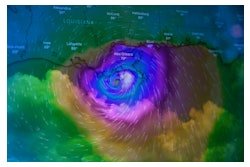

The nonprofit Maryland Soccer Foundation, which built, manages and maintains the 66,000-square-foot Discovery Sports Center in Montgomery County, has a base of more than 25,000 soccer players from which to draw. Thanks in part to large financial contributions from John Hendricks, founder and CEO of The Discovery Channel, area residents now have a pair of 85-by-200-foot indoor synthetic fields on which to play soccer, lacrosse, field hockey, rugby and flag football. (Outside are 19 more fields - including Championship Stadium, which seats about 3,500 spectators.)

The ability of the Discovery Sports Center, which opened in December, to move its soccer activities outside for the summer allows it greater flexibility than other multisport complexes, acknowledges Trisha Heffelfinger, executive director of both the center and the MSF. In March, crews removed the two fields' dasher boards and sections of indoor turf by rolling up the surface, loading it on forklifts and storing it on-site. Underneath the turf are eight volleyball and basketball courts painted on a polyurethane surface, which is applied over asphalt. (The complex's nearest basketball and volleyball competition is a one-court high school gymnasium.) On March 31, one day after the four-day turf-removal process was complete, the center hosted a major volleyball tournament on all eight courts.

Heffelfinger thinks the MSF discovered a gold mine when it opened its center to activities other than soccer. Take rugby: "That was a gift," she says. "We hadn't really thought about rugby until a league asked us about it." Plus, parts of the facility were rented out for parties 75 times during the center's first three months in business.

Just as a strategically located, well-designed and smartly programmed MAC can lift a college campus's recreation environment to new heights, a private multipurpose sports complex located in a high-visibility area with plenty of parking spaces and family-oriented programming can make a huge impact on its community (and its bottom line). Potential revenue streams flow from organized leagues, area and regional tournaments, instructional classes for players and would-be referees, facility rentals, snack bars, pro shops and practically unlimited creative-programming ideas.

The possibilities for such facilities at this early stage in the game seem endless. LANCO Fieldhouse, for one, appears poised to conquer. "We're gonna take this and do what we feel is best," Cindy Ross says. "And if somebody wants to duplicate what we've done, they're going to have to do a heck of a job."