An increasing number and range of athletes are experiencing firsthand the strength-conditioning and injury-prevention benefits of aquatic exercise

To kick off the season, each fall the Penn State University football team holds a party at the outdoor pool of the university's McCoy Natatorium, where Nittany Lion players often ham it up in the pool. It's this horseplay that sometimes puts Tom Griffiths, Penn State's director of aquatics, a little on edge. "When we have 350-pound linemen walking up to our 10-meter tower, we get a little nervous," he says. "Then they start wrestling around in the pool and I start worrying about someone blowing out a knee."

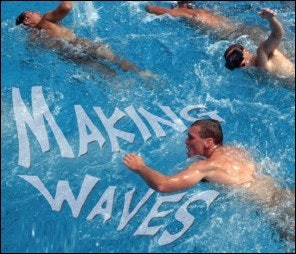

Despite Griffiths' reservations, the Nittany Lions are apparently just as comfortable in the water as they are on the football field, thanks not to their annual pool party, but rather to their regular aquatic cross-training sessions held in any one of McCoy Natatorium's three indoor pools (a shallow warm-water instructional pool, a 10-foot-deep competition pool and a 14-foot-deep, warm-water diving well). A spinoff of aquatic exercise that has traditionally been used to rehabilitate injured athletes, aquatic cross-training is increasingly being used by elite athletes and teams interested in improving strength and performance.

At Penn State, football isn't the only athletic program to have caught the water bug. The school's track and field, softball and women's basketball teams all have regularly worked out in the pool. Because aquatic cross-training can be specialized for a variety of court or field sports - from tennis to baseball to volleyball - the exercises prescribed generally mimic the movements of each sport. "If you're a jumper, you jump. If you're a baseball player, you swing a bat. If you're a tennis player, you swing a racquet," says Lynda Huey, coauthor of The Complete Waterpower Workout Book (Random House, 1993) and director of Huey's Athletic Network, a fitness consulting company in Santa Monica, Calif.

And as the athletes refine their techniques, the water's low gravity allows them to rest overworked joints and tendons. Despite near weightlessness in the water (chest-deep water reduces the body's weight by two-thirds; waist-deep water reduces it by half), the athletes still give their muscles as challenging a workout as they would on land. "They're not having to pound on the knees, ankles, hips or back, but they're still doing the same kind of anaerobic work," says Huey. "Their heart rate is still getting up to 180, 190, 200 beats a minute. It's the same workout, but without the pounding."

"Oftentimes on land, athletes do not work core stabilization muscles," adds Tim Freson, fitness coordinator for Washington State University Health & Wellness Services, which offers personalized aquatic crosstraining programs. "The water forces athletes to work on those muscles, which are critical for most movements and functions."

Aquatic cross-training also presents elite athletes with a welcome change of pace. "Think of an athlete who has to deal with the drudgery of training on land over and over again, and as a result, has muscle soreness," says Joseph Krasevec, a part-time instructor in Georgia State University's Department of Kinesiology and Health and author of Hydrorobics (Human Kinetics, 1985). "If you get him or her into the water, it changes the exercise environment. It's more refreshing to the athlete."

Yet not all coaches are sold on the benefits of aquatic exercise. Some view it as a waste of time and others are afraid of being thought of as foolish for having their athletes "play around" in a swimming pool. But if these fears have prevented some coaches from taking the plunge, it hasn't stopped the athletes themselves. Huey has worked independently with a number of notable Olympic track and field champions, including heptathlete Jackie Joyner-Kersee and sprinters Carl Lewis and Inger Miller. After being selected as the fifth pick in the 1995 NFL draft, quarterback Kerry Collins heeded the advice of legendary coach Bill Walsh and took to the water to work out a minor hitch in his throwing arm. Collins adhered to a simple routine of resistance exercises that involved fanning the water with an open palm to correct the problem. Less than six years later, Collins led the New York Giants to their first Super Bowl appearance in 10 years. Says Griffiths, who observed some of Collins' workouts in McCoy Natatorium, "It seems that athletes, regardless of the sport, are becoming very well-rounded."

"Athletic training in the water is valuable in the sense that you gain that winning edge," adds Krasevec. "The bottom line is that athletes who cross-train in the water are going to neutralize the damage they've done to their joints in normal training on land."

Those coaches who believe in aquatic exercise generally will team with physical therapists, athletic trainers and consultants like Huey to develop specialized programs for their athletes. There are also a number of organizations offering educational training in aquatic exercise, including the Aquatic Exercise Association (www.aeawave.com) and the U.S. Water Fitness Association (www.uswfa.com).

Some aquatic exercise specialists receive more aerobics-based training, while others may come from a sports medicine background. Regardless of their education, aquatic exercise specialists agree that more often than not, their first programming challenge in aquatic cross-training is helping athletes who may be inexperienced swimmers to overcome their fear of water. Even though the human body is naturally programmed to relax in aquatic environments (imagine a bubble bath or a day at the beach), Huey found that most of her clients weren't comfortable in the water when she first began training elite track and field athletes in the early '80s. Today, many of those individuals are now coaches themselves, and have become strong advocates of aquatic exercise. "They're using what they learned for their own athletes," Huey says of her former students. "They've been doing it for enough years that it's no longer strange to them."

Still, many elite athletes may feel as if they have a right to be a little concerned when taking to the water. Because of their high concentration of lean muscle mass, elite athletes tend to be less buoyant than the average swimmer. To counteract this lack of buoyancy, aquatic exercise specialists often outfit athletes with buoyancy vests or belts. Vests are typically used for training in deep water (making the body essentially weightless), while belts are used for shallow-water sessions (a belt reduces one's weight by 80 percent in chest-deep water).

But flotation devices are just the tip of the iceberg in aquatic exercise equipment. Participants employ a variety of training tools, including support equipment (such as therapy bars and hand buoys), resistance equipment (buoyant ankle cuffs, ankle weights, weighted boots, webbed gloves and dumbbells), and elastic tethers (which are used for walking-, running- and swimming-in-place intervals). Those athletes who find the pool water to be too chilly - a pool kept at 80 degrees will feel cold to many people - can slip on an insulated wet shirt or suit, although Huey says that an athlete can do without such gear and will work up a sweat almost immediately if his or her workout is doing its job.

Krasevec agrees that additional equipment isn't always necessary for an effective aquatic workout, but in almost the same breath, he admits to occasionally having placed ergometers in the pool if he felt it presented a unique challenge to that particular athlete's routine. "I've never been a big equipment person myself," he says, "but it has its value. Water exercise products have both a therapeutic value and an athletictraining value. Of course, the athlete needs greater overload in the water and that's what such products are doing. By creating greater resistance, you will get a more powerful athlete."

Not every athlete who seeks the help of an aquatic exercise specialist is looking to increase strength. There are many cases in which an athlete is hoping to rehab an injury or recover from surgery. Because of a longtime history of injury to a specific area, he or she may also opt to spend more time training that area in the water than on land. The bottom line is that just as in the weight room, one aquatic exercise program may have entirely different results for two individuals. "It depends on what you hope to accomplish," says Freson. "There's no set formula," adds Huey. "If an athlete tends to get injured, he or she would want to spend more time in the water. If the athlete is very hardy and resilient and seldom gets injured, he or she might not have to do as much pool cross-training."

There are, however, two universal principles in aquatic exercise: one, clear communication between the trainer and the athlete is essential, and two, the athlete must have a clear understanding of the work he or she is about to undergo. Entering the process, some athletes may have the misperception that because of the water's therapeutic qualities (the human body recovers from work faster in the water), they're immune from injury. Freson shoots down that notion without hesitation. "There's always risk for injury," he says. "It's just a different kind. When we're working on land, we're dealing with issues of gravity or if we're working with contact sports, we're dealing with people being hit. When we're in the water, sometimes we're dealing with issues of buoyancy or improper range of motion."

Because of a concern for accidentally pushing her athletes too far or making them do something that doesn't feel right, Huey's workouts often have a touch-and-go feel to them. Employing a technique similar to one physical therapists use with their patients in the fitness room, Huey works with each athlete to develop an informal pain meter, constantly asking questions such as "Do you feel it?" and "Is it a good burn?" She will stop the workout immediately if the athlete reports any sharp, stabbing pains. "You have to determine how to appropriately stimulate and stress the injured area," says Huey. "You don't want to cross the red line because if you cross over that line, you start to create injury."

For aquatic exercise specialists, keeping their athletes injury-free is always a primary goal, but so is providing them with a program that will translate to improved mechanics on the field or court. Aquatic cross-training is indeed sport-specific, evidenced by the creative and diverse routines prescribed to athletes in basketball, track and field, and volleyball. One program designed by Huey, for example, had former Los Angeles Laker Wilt Chamberlain hold a basketball while balancing on a therapy bar in a squat position, and practice jumping off the bar and out of the water for a "jump shot." At Penn State, pole vaulters practice their vaulting technique in the diving well, allowing them to correct improper form or other mistakes as they glide through the water in slow-motion. The forgiving aquatic environment allows Washington State volleyball players to fine-tune their serving and blocking skills, while cushioning their knees, ankles and Achilles tendons as they land.

An aquatic exercise specialist exhibiting some measure of creativity can turn just about any pool into a highly specialized training site for athletes in any given sport - and "training" is the key word. In spite of its rehabilitative benefits and relaxing atmosphere, an aquatic cross-training session is hard work and should never be regarded merely as a free day. "Aquatic exercise allows the opportunity for athletes to be challenged in a different kind of way. You can add some nice competitive elements," says Freson. "That's one of the nice things about it. The water can really challenge someone and, at the same time, make the whole thing fun."