Creative planning, combined with plenty of patience and sacrifice, helps keep college recreation facilities operating in the midst of a renovation.

By design, the space was rendered obsolete only 10 months later when the new-and-improved 60,000-square-foot Sport & Fitness Center reopened. But without that old bowling alley (which was subsequently used as a temporary training site for local polling-place workers), occupants of three residence halls and students, faculty and staff at UIC's medical, dental, pharmacy and nursing schools would have been forced to trudge a mile across campus to an equally dilapidated fitness facility that eventually was replaced in 2006.

"Even though we didn't have showers and locker rooms, a lot of people found a way to make it work," says Brian Cousins, UIC's associate director of campus recreation at the Sport & Fitness Center. "The people who were looking for a place to play basketball had to travel to the other side of campus, but for the people who were just looking to lift weights or get a good cardio workout, we had what they needed. It's pretty amazing that we pulled it off with as little complaining and inconvenience as we did."

Similar feats of operational derring-do typically are the norm wherever a rec center renovation is attempted. Recreation administrators thus face a dual challenge: keeping the renovation running smoothly while ensuring the recreation program doesn't shut down completely.

The smaller the project, the easier these goals are to accomplish. The 2005 renovation of Harvard University's Hemenway Gymnasium, for example, was of a small enough scale to be completed during the summer months, while most students were away. The upgrade of Georgia Institute of Technology's Campus Recreation Center, on the other hand, took more than two years from start to finish, repositioning the main door at a previously off-limits maintenance entrance, where users were allowed access to previously off-limits exit stairs and a freight elevator. Baldwin-Wallace College in Ohio followed the UIC blueprint for success, temporarily transferring its cardiovascular fitness and strength-training programs to an old warehouse on the nearby Cuyahoga County Fairgrounds. In most such projects, administrators are as put out as facility users. More than a dozen staff members at Oklahoma State University's Colvin Recreation Center, for instance, spent two years sharing 700 square feet of office space.

Recreation administrators involved in those projects (all completed since 2004) planned for months, trying to determine the placement of modified activity and office areas, create programming alternatives and effectively disseminate information to the student body, faculty and staff. But, as most of them will readily admit, that often wasn't enough. "It was a crazy process," says Tim Miller, Baldwin-Wallace's director of recreational sports and services. "I had a plan for everything, but there were plenty of times that I just had to plan as I went."

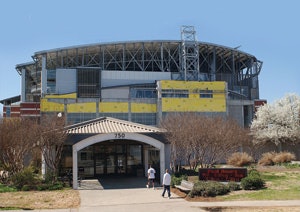

Surviving a recreation center expansion requires more than anticipating the unexpected. Large doses of patience and sacrifice also are essential. "Everyone had a great attitude up front, and that esprit de corps kind of clouded our vision of the reality," says Kirk Wimberley, Oklahoma State's associate director of recreation, referring to the "enjoyable-slash-demoralizing" interim period before the Colvin Recreation Center reopened with new fitness areas and four additional gymnasiums. "I don't believe we realized the impact of all the headaches we would have. We knew we would have them, we listed what they would be, but we didn't know how they would feel."

Michael Edwards knew there would be plenty of headaches when Georgia Tech began a two-phase project to update and connect a recreation center built in 1977 with an outdoor Olympic-size swimming venue completed in 1995. That's why the university's director of recreation spearheaded a transition committee to oversee the intricacies of how the project would affect the two facilities' users. As the university's director of sports facility planning and management at the time, Edwards invited approximately a dozen individuals to participate - including members of his own staff, the project's contractor and students. "We wanted to have a number of different brains from different areas of the operation thinking about this," he says. "But here's the curveball: You're taking a blueprint and trying to visualize how you're going to operate your building - a completely different building, really - and that presents difficulties for some people. It's very difficult to visualize what will be happening. It's much easier to do that in a building that's already completed."

Despite the challenges committee members faced, they forged a partnership with nearby Georgia State University that allowed Georgia Tech students to use GSU's Student Recreation Center via a shuttle service. Additionally, the Barbell Club, a Georgia Tech organization of weightlifters headquartered elsewhere on campus, donated 1,000 square feet of workout space.

Providing users with alternative programming options is vital to gaining their support for a renovation project. While the existing gymnasium and pool in Baldwin-Wallace's recreation facility remained open during construction, all cardio and weight-training equipment was moved to the 20,000-square-foot fairgrounds warehouse. Miller offered the choice of free admittance to that facility or reduced membership fees at a local public recreation center. The majority of students chose the warehouse, he says, which was retrofitted with additional lighting and insulation to meet building codes and given a quick makeover with surplus rubber flooring and portable rest rooms. "We basically jury-rigged a warehouse into a fitness center," Miller says. "There was also one shower in there, but nobody would have used it if their life depended on it."

OSU crews retrofitted three of the racquetball courts with temporary power to run cardio equipment, and then converted another two courts into dance studios. The south side of the small track was dedicated to a free-weights area, while the other side housed weight machines and storage. "Now, just picture basketball players and weightlifters separated by nothing but netting - those weren't always the best situations," Wimberley says.

Neither were staff accommodations at the Colvin Annex. While some employees temporarily relocated to available office space in the student union and the campus wellness center, more than a dozen front office and intramurals department staff members were crammed into a poorly heated 700-square-foot space within the annex. As outside temperatures fell below zero during the two winters they spent there, employees used space heaters, blankets, hats and gloves to keep warm. "We came real close to building a little cabin around the check-in desk and heating that," Wimberley says in all seriousness.

But uncontrollable temperatures were just one contributor to the staff's volatile collective temperament. Desks were shoved up against each other, and employees and visitors alike often would have to meander through a maze of furniture. "It was funny for the first six months, and then it became a nightmare," says Wimberley, who now realizes he should have split the staff even more among available on-campus sites. "We saw on paper how all this was going to work, but there's an emotional side to it that we overlooked. Yes, you can put 14 people in 700 square feet. But that begins to weigh very heavily on morale. I think, as a staff, we were willing, but we weren't farsighted enough to see the shortcomings of just what a condensed space would do. The tight quarters really demoralized people. Absenteeism increased. No one quit, but they got cranky."

Administrative accommodations ultimately had the opposite effect on recreation employees at Baldwin-Wallace College, where recreation, athletics and physical-education department members were relegated to four huge classrooms within a wing of the existing recreation center that did not require renovation. Miller shared a cubicle-divided workspace with five other people from his department - all of whom were accustomed to having their own office. "We knew we were eventually going to have our own wing with new offices and a conference room, so that made it a little easier," he says about the cramped conditions. "But for the first time, we were all together as an administrative staff, which actually gave us some camaraderie. We got to know each other better and made decisions just by talking directly with each other."

The changes that took place behind the scenes at Baldwin-Wallace and Oklahoma State did nothing to deter users of rec facilities at either school. "Most of the students continued their weight training and fitness training programs out at the warehouse," Miller says. "We were shocked at how many people used that place."

Wimberley concurs. "Our programs did not decline in numbers, and some intramural sports actually saw increases," he says. "So students found us. I don't think construction inhibited them at all. They just wanted to play." At the same time, however, quite a few OSU students who previously used the Colvin Recreation Center for its fitness equipment and open-gym activities opted for off-campus health club memberships - paid for out of their own pockets - simply because there was no room for them at the annex. "It's still a difficult question for me to answer: Should we have allowed more opportunities for open recreation? Right now, I don't think so," Wimberley says. "The complaints during that period of time did not outweigh the opportunities to continue intramurals and allow students to have their championships."

Throughout any renovation process, communication is critical. Savvy recreation administrators make use of every available avenue - from bulletin boards and campus media outlets to e-mail blasts and campus-wide meetings. UIC's Cousins displayed a three-dimensional model in the Student Center West detailing how the renovated facility would look, and he posted regular updates after attending design and construction meetings. He also installed in the former bowling alley demo pieces of new fitness equipment that would eventually grace the upgraded facility - generating additional enthusiasm.

"You can never do enough to show that you understand the inconvenience you're putting your students through," Edwards says. "You need to do that, because you don't want to lose their support. But the constant moving and changing of schedules and entrances led some people on our campus to think that it was a little too inconvenient to participate in recreational activities."

Nevertheless, Georgia Tech's efforts to encourage the use of alternative access points and navigational routes became so ingrained in some users that they still occasionally followed their instincts months after the renovated 300,000-square-foot facility opened in 2004. "We had students who, a year later, would walk right by glass passenger elevators, go all the way down to the opposite end of the building and try to get on the freight elevators to go upstairs," Edwards says. "We would find them pushing the button for the freight elevator, which was now key-operated, waiting for the doors to open."