Facility owners must choose climbing walls to match their patrons' abilities - lest they end up with an underutilized centerpiece.

REI's flagship store in Seattle features a realistic-looking wall that leaves climbers and non-climbers breathless - perhaps for different reasons.

Do you know who your climbing wall's users are likely to be? Because if you can picture your climbers, you can probably conjure up the type of wall that will make them happiest.

The climbing area at the University of Akron Student Recreation and Wellness Center has elements that could appeal to a wide range of climber: A 53½-foot-tall wall and freestanding bouldering arch that offer a texture and features similar to what you might find on a mountainside, manufactured in combination with a panel system that offers many flat spots for a variety of holds - and thus, a greater number of climbing routes.

"It's a great style of wall, because it looks cool, and that's important because we service all types of individuals, but it also allows us to support the local climbing community, which we need to do as well," says Andy Loue, the rec department's manager of outdoor adventure. "A lot of the more serious climbers have plywood walls in their garages. I serve students. I get the athletic-minded student who wants to challenge himself. But I also get that classic student who walks by our wall 20 times before he gets the courage to walk in and try it. And then, lo and behold, that person turns into a regular."

The climbing area at the University of Akron Student Recreation and Wellness Center is designed primarily to attract newcomers to the sport.

But where a recreation facility operator might view these planes as excessively plain, skilled climbers see a beguilingly blank canvas. Bill Zimmermann, executive director of the Boulder, Colo.-based Climbing Wall Association, notes that many facilities used in indoor climbing competitions (such as the World Cup held last summer in Vail, Colo.) utilize walls made as featureless as possible, with panels of plywood sometimes coated with nothing but clear polyurethane. The purpose, Zimmerman explains, is to minimize the use of the panel as an aid to gaining traction and finishing a route. Forced by the wall designer and route-setter to use just the available holds, the climbers ascend only in the intended sequence of moves or fall back to earth in the attempt.

$$PAGE$$

"There are a lot of old-school places that target the cult, and they're not at all concerned with the aesthetics of the wall," Zimmerman says. "They're terribly steep and difficult climbing, but they're holes in the wall. There's one here in town where I probably couldn't climb a single route - it's that difficult. It's where all the pros hang out and train. Not many cities have enough people climbing at that level to support that kind of facility."

While members of "the cult" might scoff at walls they deem beneath their abilities, it's the facilities that build walls simulating real rock that bring in the new members - and future cult members.

Loue describes the challenges his program faces, including the northeastern Ohio setting, far from any major climbing areas, and the absence of an inherent climbing community that you find in, for example, the Pacific Northwest. Yet, he says, in the four and a half years that the rec center has been open, his walls have helped create a thriving climbing culture, even given his program's other major challenge - he only has his climbers a few years before they ascend to the real world.

"We literally started at the ground level," Loue says, "and yet our numbers have increased every semester. I'm not sure how you define 'hardcore climber,' but I know I have dedicated climbers who are going through the process of being introduced to the sport, and then are becoming addicted, if you will, as most climbers do. I don't serve who the commercial gyms serve; I'm more in the business of developing climbers, not servicing climbers who are already climbing."

Loue pauses, and then adds, "I don't think there's a perfect wall out there. The wall should be designed for the clientele that you will serve, and we have a good wall for what we do."

"Most facility owners nowadays will select walls that lend themselves to a full range of climbing abilities," says Zimmerman. "You want to be able to bring in the novices and have them experience some success, train them, get them to be members, develop their skills over time, and ideally keep them as long as possible. You basically have to have terrain that goes from novice to expert."

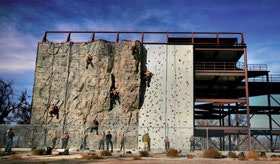

Hybrid installations don't come much more dramatic than this outdoor wall at Kirtland Air Force Base, N.M.

Manufacturers of freeform systems can create all sorts of features to challenge and confound climbers of all levels, including pockets that can only hold two or three fingers, razor-thin edges, different degrees of slope (including overhangs) and rough rock faces that suddenly, and alarmingly, go smooth. On both real-rock and flat panel systems, an array of holds - from larger "roofs" and "slopers" to smaller "crimps" and "pinches" - serve the same purpose, and have the added benefit of aiding flexibility when setting routes. What makes freeform-style walls problematic is that the undulating surfaces don't allow for the use of many larger holds (those that require a flat surface to avoid spinning or breakage) and limit hold placement in general.

$$PAGE$$

Dan Hague, a managing partner in Climbing Wall Management LLC of Washington, D.C., admits to the climbing-gym-goer's bias - real climbers don't like real rock - even as he expresses an admiration for what wall manufacturers are able to accomplish aesthetically.

"They look fantastic, but with a freeform wall you can't make a section of wall more difficult than the holds that are formed into the surface," Hague says. "It just limits what you can do as a climber."

While Hague believes that such difficulties will almost always limit a wall's appeal - "If the aim is to provide a wall that people will enjoy once in a while, maybe that's the best product," he says - he nonetheless feels that underutilization of climbing walls is most often due not to the type of wall selected, but to poor wall management.

"There are any number of reasons why climbing facilities are underutilized," he says, listing poor route-setting, restrictions on the use of gymnastic chalk and limited hours of operation. "Everybody wants to have a climbing wall, but they're not the easiest things to manage. It's not like having a treadmill, where you just put it out there and people use it. It has to be managed constantly."

Loue is the Akron wall's primary route-setter, but students do it, as well, as part of their climbing education. One of the things they learn is that while an obvious objective is to keep climbers engaged and interested, there are more serious risk management issues involved. For example, the natural formations in the freeform wall must always be taken into account so one climber on a ledge isn't in danger of being struck by a second climber, or so a climber doesn't reach a certain point in the wall and then get stranded.

Increasingly, sculpted rock formations including ledges and fissures are seamlessly combined with flat, untextured panel systems.

That said, many climbing wall owners throw volunteer users into route-setting - a typical inducement is a reduced-price membership - something that rankles a lot of industry pros.

"What's particularly frustrating for me is that people will spend $300,000 on a wall and they won't spend $5,000 to get their staff trained to use it properly, or train some of their staff to become proficient in route-setting," Zimmerman says. "It's mind-boggling to me."

"Management of a wall is a specialized activity," adds Hague, echoing the plea for avoiding volunteers. "There are a lot of climbers out there who don't have any expertise in managing a wall. It's a big jump, even if you know climbing."

Alongtime climbing industry veteran recalls a meeting that took place last year in a conference room at a major Midwest university. At issue was the climbing wall, the type of which had not yet been selected. On one side of the room sat representatives of the school's administration and recreation department, all of whom were advocating the purchase of a stunning, enormous pinnacle of real-looking rock. On the other side of the room sat representatives of the school's climbing community, nearly all of whom were opposed to the grand architectural statement.

Increasingly, the option selected is ... both. And the result appears to be greater engagement of climbers at the outset and over time, and the ability to demonstrate the breadth of the outdoor climbing experience indoors.

"Some people learn how to climb inside, some learn outside," says Loue. "Those who learn inside are more attuned to bouldering, and sometimes they don't like the variety our big wall provides - it gives them too many options. Those who learn outside really appreciate the wall's natural features. There are definitely different ways to learn rock climbing."

Read Next

New Product Roundup: Fitness | Outdoor Surfaces

April 17, 2024