Local YMCAs enjoy operational autonomy, but the national Y ultimately determines financial viability.

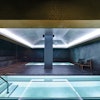

Photo of the the 121-year-old Central Valley YMCA in Fresno, Calif.

Photo of the the 121-year-old Central Valley YMCA in Fresno, Calif.

These are tough times, as everybody knows, and nonprofits in particular are being hit from all sides. Charitable contributions are down, as are revenues from program and membership fees. YMCAs, with their promise of reduced and even free entry for poorer members of the community, face a particularly difficult path through this uncertain economy.

The smaller the Y, or the smaller the community served by that Y, the less certain that survival becomes. Operational autonomy in such circumstances - a limited pool of potential donors and members - might become something to be feared rather than enjoyed.

When Ys begin to experience extreme financial distress, there are occasions - about five a year, according to the YMCA of the USA - when charter revocation becomes a distinct possibility and the narrative of local control is completely rewritten. The result is often chaotic, according to newspaper reports. In Bonaire, Ga., for example, the closing of the Houston County YMCA last December was so abrupt that Y employees told The Macon Telegraph of bounced payroll checks and reneging on promises of reimbursement for personal expenditures made on behalf of the Y "to keep the doors open." End users who had purchased memberships just days before the closure were similarly aggrieved, while most board members either refused comment or could not be located by reporters. One part-time yoga instructor offered this blunt assessment afterward: "This is a Christian organization that regretfully may not have lived up to its core values."

If the YMCA of the USA regrets the way it is sometimes portrayed in the wake of a closure, you'd never know it. As a matter of routine, the national organization will not answer questions about specific charter revocations, or even general questions about the criteria used to determine a Y's viability. Two weeks of AB queries elicited the standard line from the national Y's marketing and communications spokesperson, Mamie Moore: "It is YMCA of the USA's longstanding policy not to discuss specifically why a YMCA loses its charter," read her e-mail response. "We can say that YMCAs are expected to meet certain standards, and Ys that lose their charters fail to meet those standards." The response of Linda Bowers, the national organization's member compliance administrator, was more succinct - "I cannot answer your questions" - though she repeated it five different times.

Reached by telephone, Moore said that individual YMCA administrators were free to discuss these issues. However, every YMCA branch or association director contacted for this article either refused comment from the outset or at a certain point put a stop to the interview. Those who did speak prior to pulling the plug were able to at least verify the existence of standards. "They're pretty clearly spelled out," said Pat O'Brien, president of southeastern Wisconsin's YMCA of Dane County Inc. "Most Ys meet or exceed their charter requirements," added George Scobas, chief operating officer of the Valley of the Sun YMCA in Phoenix.

The Houston County Y closure dismayed some members of the community because of what they perceived as the YMCA of the USA's callousness, but the organization has never purported to be anything but a "national resource office," as Moore calls it. (The local Y board's only member to be both found and willing to speak, complained to the The Macon Telegraph that "they absolutely refused to do anything to help out.") Nonetheless, YMCA directors are uniform in their praise of the national organization's support of local branches - even if, again, they offer few specifics.

"I think if you operate a good YMCA, having the support of the national Y is definitely a benefit," says Dick Webster, executive director of San Diego's Mission Valley YMCA. "And they're not dictatorial - as long as you meet the standards."

A close reading of newspaper accounts and a few off-the-record comments help flesh out what those standards might be. YMCAs are audited by the national Y annually, and pay dues equal to an unverified 1 percent of annual revenues, with dues capped at an undisclosed level. Since there appears to be no limit on how much debt a particular Y can carry, the primary reason for a revocation may well simply be nonpayment of dues.

Two other possible standards went unmet by the 121-year-old Central Valley YMCA in downtown Fresno, Calif., which lost its charter in May. The first was member fees - the Y had over a period of years seen its membership erode as residents in the downtown core moved to outlying areas. "Community size" (specified as "a minimum year-round permanent population of 25,000 residents within a 12-mile radius of the location under consideration") is one of three "minimum capacity requirements" leading off the YMCA of the USA's questionnaire that potential program operators are asked to fill out when seeking a Y charter.

The other obstacle for Fresno officials was its lack of fundraising prowess. John Shehadey, president of the Central Valley Y's board, told the Fresno Bee that YMCA of the USA had set a $500,000 threshold to guarantee solvency, but the Fresno group had raised only about $100,000. ("It's hard to get large donors to come forward in a very short time," Shehadey said.) That $500,000 figure is specified in the third of the three "minimum capacity requirements" - "Community has the capacity to initially raise a minimum of $500,000 for three years of program site operations," it reads, "and can develop and document a system for ongoing and long-term fundraising capacity to sustain the future of the YMCA as a charitable 501(c)(3) organization."

The possible standards cited in Houston County Y's case aren't quite as quantifiable. One board member made a request for 90 additional days to raise $250,000 in a Nov. 25 e-mail; on Nov. 26, Donald McCarthy, a YMCA of the USA field service specialist, denied the request while voicing concerns about the local leadership and noting a lack of a "strategic or tactical plan in place" to deal with continued debt. Any approach to donors, McCarthy wrote, "could be viewed as deceptive fundraising and tarnish the name of the YMCA."

The number of YMCAs nationwide continues to rise, to 2,686 branches at the end of 2008. The work of keeping programs afloat is performed locally, as always, and YMCA directors are on the whole nonplused by the responsibility. Dane County's O'Brien notes it's like any other business; you have to have a financial plan in place so you have enough money to sustain operations, pay staff and maintain the building. "We do not get financial support from our national Y," O'Brien says. "We have to stand on our own."

The possibility of losing that autonomy should hard times get harder, O'Brien adds, doesn't really enter the picture. Having your charter revoked is just too rare.

"Usually when that happens, it's in a small community, in kind of a remote area, possibly, and the Y in question maybe just doesn't have enough people to sustain it - that kind of thing," O'Brien says. "It doesn't happen a lot, because obviously the national Y is going to do everything in its power to try to keep them as a YMCA. It usually only happens after all other efforts have been exhausted."