Strength and Conditioning Coaches Weigh Their Options Amid an Abundance of Diverse Techniques Designed to Enhance the Performance of Today's Elite Athletes

Strength and conditioning specialist Skip Allen assesses the current state of his industry, with its abundance of buzzwords and corresponding training techniques, as a veritable free-for-all of fitness philosophies. "You can line up 100 strength coaches in a row, and they're all going to have their own way of doing things," he says.

The number of ways in which Allen - who left the NHL's Colorado Avalanche in 1999 to launch Peak Performance, an Englewood, Colo.-based sports performance academy for kids - can go about his business these days is growing faster than a 14-year-old in the midst of a metabolic spurt. And the same goes for Allen's colleagues at all levels of organized sport.

"There's so much out there," says Arizona State University's Joe Kenn, the National Strength and Conditioning Association's 2002 Coach of the Year. "What are the buzzwords now? Core training. Proprioception. Prehab. Where do you go?"

Indeed, the paths by which athletes and teams may go about improving physically vary widely, with some strength and conditioning coaches embracing such concepts as core training (strengthening the muscles of the abdomen and lower back), proprioception (enhancing balance) and plyometrics (jump training). Other coaches dismiss such efforts as "fads" and the equipment used to incorporate them (stability balls, wobble boards, jump boots and the like) as "gadgets." Whether or not these constitute special times for strength and conditioning coaches, it's clear that training elite athletes is becoming ever more specialized.

Consider core training, which has created more buzz than anything strength-related in recent months. The core consists of the 20-plus muscles comprising the torso area from mid-rib cage to the hips, including the internal oblique, transverse abdominis and erector spinea muscles. The trick is figuring out the best way to strengthen those muscles, which serve to stabilize the entire body.

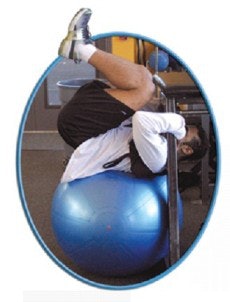

"Training that part of the body is no longer about coming in and doing three sets of 10 bent-knee sit-ups or two sets of 25 crunches," says Kenn, who incorporates core strength exercises into every one of his players' workouts. Unlike the supine pursuit of "six-pack abs," most core work is prescribed with the athlete in a vertical position. It might entail jumping onto a wobble board perched atop a box or lifting a weight while balancing one-legged on a foam pad. "We don't do any regular crunches or sit-ups at all," says Dwight Daub, strength coach of the NBA's Seattle SuperSonics. "We do stuff that's on the edge of not being safe, but safe. We push the envelope a little bit."

The only thing pushed by University of Connecticut women's basketball players this past season was weight attached to barbells, and that was just fine with strength and conditioning coach Andrea Hudy. It appears the no frills regimen, heavy on Olympic lifts and dictated by the renovation of the team's Gample Pavilion headquarters, also agreed with the Huskies, who this April capped a 35-1 season by successfully defending their NCAA championship. "We didn't even have dumbbells if someone wanted to do, say, stabilization work," says Hudy, an open skeptic of placing athletes in unstable workout settings anyway. "I want to increase the athlete's strength. The court surface doesn't change. Am I going to put a basketball player on an exercise ball and ask her to push weight over her head? No, I'm not going to do that."

Hudy views the torso as a body part, and incorporates front, side and rotational movements into the Huskies' workout routine. But until core strength can be measured, she's not willing to jump on that bandwagon. "You test vertical jump. You test bench press. What's a core test?" she asks.

Just using proper form when performing certain standard weight-training exercises will engage the core muscles, according to Jeff Connors, associate athletic director for strength and conditioning at the University of North Carolina. "If you perform closed-chain multi-joint movements, such as the back squat, you're going to have to develop some core strength just to be able to perform that movement," says Connors, among 36 coaches so far to achieve master status through the three-year-old Collegiate Strength & Conditioning Coaches Association. "I think the thing that's new about it is that people have devised multiple ways of training the core area."

"It's the new buzzword, but if you go back and look at a lot of spinal injury rehab centers, they have been doing this in rehabilitation for years," Allen says. "The strength and conditioning world finally got smart enough to recognize that if it works in the rehabilitation of people's injuries, it's certainly going to work in the prevention of injuries."

In fact, the term "prehab," as Kenn points out, has earned its own place within the modern sports lexicon, but by no means is it limited to an athlete's core. "If a kid tears his rotator cuff, there are certain specific exercises that the sports medicine staff is going to use to help strengthen that area. Well, why not take those exercises and implement them with all your healthy individuals so they never get into that situation?" Kenn asks. "We do things during our post-workout for the elbow, wrist, hip, shoulder, knee and ankle. Our guys like it because they know we're looking out for their best interests."

And the team's. After all, no matter how physically gifted they may be, athletes who can't play can't produce. Says Allen, who worked for the Denver Broncos during that team's Super Bowl seasons of 1997 and '98, "John Elway could be the strongest guy in the world, but if he's injured he doesn't make any difference."

The first step in making athletes stronger and less susceptible to injury is determining if any potential injury-causing weaknesses or muscle imbalances exist. Before athletes don parachutes for sprinting resistance or surf wobble boards to build core strength, they are often asked to perform a simple, flatfooted squat while holding a broomstick at full extension over their heads, a motion that may uncover instability in the ankles, knees and hips. "That probably is the single best exercise to be able to identify problems in terms of joint stabilization," says Loren Seagrave, founder and chief performance officer of Alpharetta, Ga.-based Velocity Sports Performance. "Your pyramid of athletic success is based on the first floor being fundamental movements and the second floor being athletic performance. Too many people skip the first floor. They want to get to the sexy exercises right away."

The broomstick is only the beginning. "We run through a series of 14 tests and basically document where people's problems are, and then put together a prehab program," Seagrave says. "We don't wait for people to get injured. We address the problems that are potentially going to cause injuries in a prehabilitation, rather than a rehabilitation, exercise program."

Just as individual athletes carry their own injury history, the sports they play and the movements required to play them can serve as predictors of future problems. "The prehab for basketball is different than the prehab for softball," says Hudy, who offers that example as someone who works with both sports at UConn. "Whereas basketball prehab for women has a lot to do with the knee, softball would have more to do with the shoulder."

Because women are as much as eight times more likely to incur ACL injuries than men, Hudy has paid particular attention to the jumping and landing mechanics of UConn's women basketball players. She even has athletes perform running and jumping drills backward to enhance awareness of their bodies in motion. She also notes that the position of a player's hands relative to her body has never been standardized in ACL research, and thus takes it upon herself to examine a variety of player body contortions during prehab exercises. "We put an athlete in an awkward position based on where they're holding the ball and have them jump, but as a controlled, low-level plyometric activity," Hudy says. "People say, 'You're teaching them to get hurt by putting them in that position.' Well, no. We want to teach them to get out of it."

Daub structures his prehab programs to deal with the indiscriminate condition known as jumper's knee, or inflammation of the patellar tendon. High-stress, open-chain movements such as the leg extension, which develops the quadriceps but little else, are scrapped in favor of squats, step-ups and lunges. "To avoid jumper's knee, you have to keep a really good balance in the quadriceps-hamstring ratio," says Daub. "That's critical when it comes to an NBA season, because of the duration of it and the wear and tear on players."

As conditioning healthy athletes becomes increasingly sport-specific, rare is the sport that can't be further broken down by position. The desired result is functional strength, which according to Daub allows an athlete to be effective at a particular position in a particular sport. "People are doing a lot in terms of strength and power in the weight room," Seagrave says. "But the key is to be able to take that strength you develop there and put it to use on the field of play."

"It's a real science now," says Rosalin Hanna, who prescribes different workouts to pitchers, catchers, infielders and outfielders as strength and conditioning coach for University of Arizona baseball. For catchers, who assume the most physically demanding position on the diamond, Hanna focuses on improving lower body strength, lateral movement and foot quickness. Instead of straight-on step-ups, her catchers perform lateral step-ups, in order to hit the gluteus muscles from a different angle. Strength training exercises targeting the upper body, such as the seated row and lat pull-down, are performed by the catchers while in a crouching position - "a position that replicates their position on the field," Hanna says.

In football, where utilizing separate platoons of players specializing in either offense or defense has been the norm since the 1960s, different positions require different workout regimens. Connors, who works most closely with the UNC football team, stresses to his defensive players the importance of acceleration, deceleration and reacceleration - an explosive start, a quick stop and another explosive start in another direction. ADR, as he calls it, is manifest through practice drills that mimic 10 or more movements common to a given position in a high-tempo progression. "ADR is more suited toward defensive players, because ADR is reactive in nature," Connors says. "Most offensive position groups know where they're going. Defensive players don't. They have to react to the movement of other players."

ASU's Kenn, meanwhile, leaves such fine-tuning of athletes to each sport's coaching staff. "Come to my weight room and you'll find nothing very sport-specific about what we're doing," he says. "Our role is to improve athleticism. Coaches are specifically trained to make an offensive lineman better or a basketball player better. We feel that if we can give the coaches a better athlete, they've got a better chance of making them a better player."

That said, he does incorporate weight room techniques easily transferred to the playing field. "Our goal is to move a resistance from Point A to Point B as fast as we can move it," says Kenn, whose "dynamic bench days" require athletes to perform three bench-press repetitions within three seconds. "That is taught, because most people who walk into our weight room for the first time have been exposed only to the body-building theories of training, in which you improve muscular size, and strength is a byproduct of that. The bar is moved in a slow, methodical manner. But if it takes me four seconds to bench press from chest to extension, I'm not going to win on the football field."

When talk turns to athleticism, strength is often mentioned in the same breath as speed. And the time-worn cliché, "You can't coach speed" - propagated by game-day panelists such as Jerry Glanville - irks people like Seagrave. "Speed is a skill," he says. "The fastest people in sport have accidentally discovered how to be fast; everybody else is just waiting to be taught. We have tremendous patience in teaching the young athlete how to throw a tight spiral, but precious little patience when it comes to allowing someone's speed to be developed."

Seagrave, regarded as one of the premier speed coaches in the world, seeks to reprogram athletes to properly recruit the muscles necessary to run faster. It's a four-stage process that takes the athlete from unconscious incompetence (not thinking about what's being done incorrectly) to conscious incompetence (realizing what's being done incorrectly) to conscious competence (knowing what's being done correctly) to unconscious competence (not having to think about what's being done correctly). It's basically replacing ingrained bad habits with programmed good ones. "Through systematic perfect practice, it evolves into a very complex set of reflexes in the nervous system," Seagrave says.

Faulty form can be pinpointed just by observing an athlete and measuring his or her joint angles (think broomstick squat), but the tweaking process is aided greatly by state-of-the-art technology. Video images of an athlete-in-training are superimposed over footage of an athlete that Seagrave has already honed into a technically sound runner using technology that debuted during broadcasts of the Salt Lake City Winter Olympic Games (think downhill ski run comparisons). Meanwhile, contact mats linked to sophisticated computers gather data from a runner's final few strides in the 40-yard dash.

The goal, over a six- to eight-week program, is to reduce by 0.005 seconds the time it takes a runner to apply force to the ground while his or her foot is planted there, then shave another five milliseconds off the time it takes to return the foot to the ground after it's airborne. "If you save one one-hundredth of a second every step for 20 steps, you just ran the 40 two-tenths of a second faster," says Seagrave, who has seen offensive linemen lop four-tenths off their 40 times, which can translate to hundreds of thousands of additional dollars in the NFL draft. "You need to reduce it to the ridiculous, break it all the way down and show the athlete that it's not really that difficult to do."

Still, even the strongest, fastest athletes can be beaten if they lose concentration. Connors' fascination with the effects of fatigue on UNC football players, who sometimes fail on the field despite having spent an entire week in the classroom poring over their opponent's tendencies, has led him to develop a test to improve concentration under physical duress. He has a player run for five to eight minutes on a treadmill, then continue running as the player answers grade-school-level math and verbal questions presented by coaches with cue cards. Another coach times the athlete's responses with a stopwatch. Correct answers are tabulated. "What we're trying to find out is if that individual can improve mental focus during a state of fatigue," says Connors, who ultimately envisions asking questions specific to the upcoming opponent while fatigued players watch game film. "I'd be interested to see if that would help them perform better," he says. "It's going to take some money. It's going to take some time. But it's certainly something I think about."

Strength and conditioning coaches have plenty to think about these days, as the profession continues to evolve. "The older I get, the more I find that I don't know," says Connors, who's been a strength and conditioning coach for 16 of his 47 years. "What makes this profession interesting is that new things are constantly being discovered. Every year that I've been in this profession, I've learned something new."

"Back in the '70s, it was just go in and throw some weight around and get stronger, and that was it. If you lost some flexibility, no big deal," says Daub. "Now, you hear a lot about functional training, core training and training to increase lean muscle tissue, speed, agility and jumping capabilities."

The key to any strength and conditioning program, no matter how progressive, is communicating the reasoning for the chosen methodologies to the athletes they are intended to benefit. When Kenn played football at Wake Forest in the mid'80s, he did what the coaches told him to do, no questions asked. Now coaches have to earn the athletes' buy-in. "This is a day and age in which athletes want to know why," he says.

Likewise, strength and conditioning coaches need to question each new training development before abandoning the very approach that accompanied their own professional ascension. "Some of these things are important, don't get me wrong," Kenn says. "But what got you there is what got you there, and that's ultimately what's going to keep you there. Ask the question, 'How does this stuff fit into what we believe?' If you can figure that out, the sky's the limit for any program, regardless of your philosophy."