Based on eight years of work as an expert witness in the wake of Korey Stringer's August 2001 death on a Minnesota Vikings practice field, Doug Casa, a kinesiology professor and director of athletic training education at the University of Connecticut, was approached by Stringer's widow Kelsi and the NFL about establishing a lasting legacy for Korey, who was 27 at the time of his fatal heatstroke. The Korey Stringer Institute turns 10 this year, and its work to combat exertion-related illness and death — which continues to garner multimillion-dollar grants — transcends the playing field to include laborers and soldiers. AB senior editor Paul Steinbach asked Casa for a report on the institute's progress pertaining to sports.

What has the institute's 10th year looked like?

Just this past spring, we received a $3 million grant to try to put athletic trainers into school districts that have never had them. The project is actually going to be in the summer of 2021, when we're going into some major cities that have had school districts without athletic training services to try to figure out solutions for sustainable athletic health care. That's exciting.

Are the numbers of athletic trainers serving high schools headed in the right direction?

Oh, yeah. I would definitely say in the last 10 to 20 years, we've seen a gradual increase in athletic training services at the high school level. A lot of those schools have more than one athletic trainer now, because you're talking about schools that have 700 or 800 athletes, or that might have 20 or 25 sports at their high school. It's overcoming hurdles with the schools that don't.

How do you go about that process?

KSI works really hard on a program called TUFSS — Team Up for Sports Safety — and we're visiting all 50 states to try to enhance health and safety standards for high school sports. We're having meetings in all 50 states where we bring together the key state high school athletic association officials, coaches, athletic directors, principals, superintendents, physicians, athletic trainers — 20 to 30 people in each state sit down for a two-day meeting. We go through the key policies that that state does not have to work toward trying to enhance their policies. It might be something for heatstroke, or for cardiac issues, or for head injuries, or for emergency action plans for athletic training services — really key, top-level kind of items. We've done 13 states so far, and we've had phenomenal success. In just the past few months, Louisiana, New Jersey and Florida have had massive legislation work its way to the governor's desk, where it was signed by the governor into law, and that all emanated from our state policy meetings.

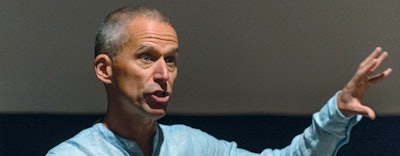

From AB: The Athletic Business Podcast: Beating the Heat with Dr. Douglas Casa

What guides your analysis?

In 2013, a document was released on preventing sudden death in secondary school athletics. That's the roadmap, if you will, for everything we've been doing since 2013 to try to get states up to snuff on everything that was in that 2013 consensus statement. Fourteen organizations endorsed that document, including the National Federation of State High School Associations and the National Athletic Trainers' Association. We were one of the member groups, as well. But where we did the legwork was we took that 2013 document and basically made 100 sentences out of it, and basically made a checklist: "Do you have or not have each of these recommendations?" We spent the next three years going through all the states and all their legislation, and all their state high school athletic association policies, and we created kind of our roadmap for who has what and who needs help with each particular item, so we know every state stood on all 100 points on the rubric. When we say we're helping states modify policies, we're trying to get them closer to 100 on that rubric. New Jersey is the highest, and they have 85 out of 100 points.

What are examples of rubric points? For instance, are cold-water immersion tubs required during summer conditioning and practice sessions? Heat stroke is 100 percent survivability if treated in a cold-water immersion tub. We have 15 states now that require cold-water immersion tubs during those practices. That's one example. Another one would be access to an AED within two to three minutes on a sports field. Not just one posted in your school, but is it accessible during athletic events? So big-ticket items. The three leading causes of death in sport are head injury, cardiac and heat stroke. They account for almost 90 percent of all deaths, so these policies are largely geared toward those three items.

Is a tub required at every practice?

I wouldn't say every practice. If environmental temperatures exceed a certain threshold, that would kick in the state requirement. You're not doing it when it's 48 degrees outside, but if it exceeds a certain threshold, then some of those standards have to be met. That's just one item out of 100.

In terms of state rubric performance, Connecticut ranks fairly low at 39th. Minnesota, where the Stringer incident occurred, is even worse — 46th. Is there personal frustration in those numbers?

There is, but it also gives us motivation that our work is needed. I'm going to be honest. It really just comes down to the leadership in that particular state — either the state high school athletic association people or someone from the state sports medicine advisory committee. You need someone from those entities to really take the lead and push this stuff through. Why New Jersey is great, and why Florida has jumped from 23rd to fourth or fifth, and why Louisiana just added 30 points to their score is because each of them had an individual person who was willing to do the legwork, who works in that population and is serving those constituents. But we're making great progress. It's motivation. If everyone had a score of 100, you and I wouldn't need to chat right now.

UConn was the first FBS school to cancel football in 2020, and then Big Ten parents petitioned the conference to reverse its football cancellation. At UConn, the players convinced the coach to pull the plug. What is it about UConn?

It's a good question. I'm sure there were a bunch of players at UConn who wanted to play. I'm sure it was a mixed bag. UConn faced a really unique circumstance that was different than most other schools because it's an independent in football, and basically our schedule was evaporating in front of us. A lot of conferences were not playing non-conference games, and then we were going to be traveling to states that are on our list requiring a 14-day quarantine when we come back. It was just becoming a logistical nightmare. And I think a lot of those kids wanted to retain that year of eligibility. They'd rather have a quality year, instead of kind of a wasted year. I think that was one of the big reasons for the UConn path.

When you see high schools trying to play football amid a pandemic, how do you react to that personally?

I'm a fan of sports continuing, to be honest with you. I think there's so much upside to sports that we need to figure out strategies that we can still do sports and keep them as safe as humanly possible. But the reality is — and I don't think most people think this way — there's a really good chance we're going to have this for the next two to three years. Everybody thinks that a vaccine is going to come and it's all going to go away, but I think there's a really good chance we're going to be in this situation for a while. I'm not a believer that we should not have sports for the next two or three years. I think that just would affect too much — a lot of negative implications of not having kids playing sports for a couple-year stretch.

Do you hold it against the Big Ten or Pac-12 for pulling the plug this season?

No. Everyone has their reasons. Everyone has different data that they're looking at when making that decision. There are great leaders in conferences that are moving ahead and ones that are not, and it just shows you that it's not completely clear cut. It's not so black and white that you know it's a yes or it's a no. Really tough decisions have to be made. I'll give you an example of the high school level. For someone to just cancel all fall sports, I think, is silly. Cross-country running — you don't necessarily have teams run against each other to have a competition. You could have Team A start at 10 o'clock, and they post the top-five fastest times. Then 10 minutes later, Team B goes out there and you add together their five best times, and you have a winner and a loser. It's a real competition. and they don't have to be on the course at the same time. My point is, you can find creative solutions. You have a senior in high school who's never getting that season back for cross country. It's not like in college where he can stay around another year, right? No. He's never getting his senior cross-country season back. And you could still run, and you could do it safely. I think in high school sports, maybe moving to a regional-based schedule. If you live in a big state, don't be driving three hours in a bus and stopping at restaurants and gas stations. Switch to a regional schedule, even if you just play everyone within 30 or 40 minutes and have to play everybody twice in a home and home. I think there are a lot of different things people can do to try to make it happen. I am not a fan of canceling sports. I wasn't a fan of the Big East, the conference we're in here at UConn, canceling fall sports. I didn't support that decision.

Some high school cross country competitions will feature mask-wearing at the start and finish of races, as well as wide-open finish lines versus a cattle chute.

It's that kind of creativity we need at a time like this. I don't want to take the season away from the kid. I like the idea. I don't have any problem with a kid wearing a mask for the first 100 meters of a race, if you are racing against other teams, because that's when you're close to other people and then it spreads out. If you have a 100-yard-wide finish line, that's fantastic. We don't have to funnel to a 3-yard-wide finish line. If everyone's running the same distance, who the heck cares? I'm just for people being creative right now. There are some circumstances I think that are super challenging. I do think football at the high school level is one of the most challenging circumstances we have right now. I think it's easier at the college and pro levels, because they have more resources to do certain things to keep players safer. And they can test people more often. You have more control over the situation than I think you do at the high school level. The NBA bubble is the perfect example of what resources can do for you. Nobody can come into that place unless they've been tested and follow this long litany of policies to get in there, and that's why they've had — knock on wood for them — such good success. And it's so awesome to see them playing again.

We're seeing communal hydration stations banned from sidelines as one measure to mitigate coronavirus spread. Has the pandemic changed the ways you go about your work ensuring the safety of kids?

To me, it definitely shows the need for an athletic trainer — now more than ever. Remember, kids are rolling off four or five months that they haven't played organized sports. Some people weren't active at all. Fitness status is going to be much more variable than ever before. I am a huge fan of having individual hydration — having your own water bottle. Just have a huge jug and maybe have one person who has gloves on who is filling up the water bottles and having a way that they can hand it back, so you don't have a hundred hands touching the cooler, and you're only touching your own water bottle. I'd rather sit in a room and figure out these things than just say, "We're canceling." I always come back to the same thing — the seniors in high school. This is it. They're never going to get it back again. Do we help them figure it out, or do we say, "You're done"? If you're a fall sport athlete, and it's your only sport and you're a senior in high school, this is it. I would honestly just rather figure out a solution for them, if we can. And I'm not talking about a state where things are horrible with the numbers, obviously. Then it's just not feasible. You might have to postpone, move it to the spring, postpone it a couple months to start. But in states that are managing it quite well, can we figure out a solution?

Is the institute where you had hoped it would be at the 10-year mark?

It's a good question. I do media all the time and that's the first time I've had someone ask me that. I think we're humbled and super proud of the work that we've done. We've had a massive impact across a lot of different levels of sport and work settings, but I think also that the work we've been able to do has also shown that there's just still so much work to be done, because nobody was really doing this beforehand. I think the thing we're maybe most proud of is that we realized that an organization like ours was really needed, because there wasn't an organization out there that was really advocating for the worker or the athlete's health and safety issues during intense exercise or labor. There are just so many things that we're constantly working on. It gives us a lot of work to do, but it also gives us a lot of satisfaction when stuff gets done.

It has to be intensely rewarding.

I always tell people I sleep really well at night. When you think about states that have hundreds of thousands of high school athletes currently, and they'll have that many in the years to come, we're changing policies that are dramatically changing the landscape for their health and safety.

Are we seeing the number of deaths, heat-related or otherwise, come down?

To be fair, for what we're doing, our state policy initiatives have all really been happening the past few years. We just started TUFSS a couple years ago. Thankfully, the numbers in our world are not massive. It's not like we're dealing with 300 a year and we're trying to get it down to 200. We're talking about five, six, seven deaths a year from heat stroke at the high school and college level combined. We're doing things to make things better, but remember there are also things happening that are making things worse at the same time. Even if we see numbers stabilize, we may be doing a good job. For instance, global warming is making everything harder every single year. It's so much warmer now than it was 30 years ago for a high school athlete in Georgia. And the amount of supplements and performance-enhancing drugs used at the high school level is so different than it was 30 or 40 years ago — ephedra-based things and all these energy drinks. We have a different population that we're dealing with right than we ever had before. There's a lot of other work that has to be done.

It's going to keep you busy.

It will.

This article originally appeared in the October 2020 issue of Athletic Business with the title "Korey Stringer Institute at 10: Pride in progress." Athletic Business is a free magazine for professionals in the athletic, fitness and recreation industry. Click here to subscribe.