Investing in Cardiac Emergency-Response Technology Is Making Increasing Sense for a Number of Athletic, Fitness and Recreation Organizations

Each Thanksgiving, Mike and Janet Handl have a lot to be thankful for. This year's holiday will be the third since their 16-year-old son, Craig, collapsed during a morning basketball game outside his school in Manitowoc, Wis., on Nov. 17, 1999.

Just before losing consciousness, Craig clutched his chest and turned pale. Paramedics arrived on the scene three minutes later. By that time, Craig had stopped breathing and attempts to revive him with CPR were unsuccessful. The teenager's heart had fallen into ventricular fibrillation - a condition during which the heart experiences an electrical malfunction and quivers erratically - rendering it unable to pump blood to Craig's brain and the rest of his body.

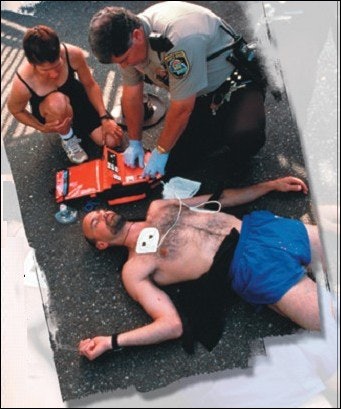

For Craig's heart to return to its normal rhythm, it would require an immediate defibrillation shock from an automated external defibrillator (AED). No larger than a laptop computer and lighter than most briefcases, this device is capable of delivering a precise electrical shock to the heart via two electrode pads applied directly to the victim's skin. AEDs are simple to operate and designed to guide users through each step of the emergency response, determining first whether the victim truly requires defibrillation or another form of medical treatment, before administering an electrical shock. But time is of the essence. According to the American Heart Association, with each minute that passes after the heart enters ventricular fibrillation, a victim's chances of survival decrease by 10 percent.

Considering those figures, it's amazing that Craig survived at all. His heart was not defibrillated until he reached a nearby hospital emergency room, some 21 minutes later. Craig beat very steep odds: The AHA estimates that 225,000 individuals in the United States die each year from sudden cardiac arrest, claiming nearly twice as many lives as breast cancer, prostate cancer, house fires and automobile accidents combined.

While some victims of sudden cardiac arrest do have family histories of heart disease or abnormalities - as was the case with the Handls - the majority do not. "Often, there are no symptoms," says Stuart Berger, a cardiologist at the Children's Hospital of Wisconsin Heart Center in Milwaukee. "Sudden cardiac arrest sometimes is the first indication."

That is why Berger and a growing cadre of advocates - medical professionals, athletics administrators and concerned parents among them - are working to make the inclusion and availability of AEDs a standard of medical care in high school and collegiate athletic and recreation facilities. In addition to his work with the Heart Center, Berger is a leading proponent of Project A.D.A.M., a collaborative undertaking seeking to make AEDs available for use at all Wisconsin high school sporting events. Initiated in 1999, the project is named after Adam Lemel, a Whitefish Bay High School student-athlete who died during a basketball game. "I'm not advocating that every school in the country have this," says Berger. "But for the schools that want AEDs, we'd love to facilitate the process. I think it's going to save lives."

Terry Gordon, a cardiologist at Akron General Medical Center and former president of his local AHA chapter, is fighting for a similar cause in Ohio, with considerable success. "It's said that each year 6,000 lives are saved by smoke detectors," says Gordon. "We believe that 100,000 lives can be saved by AEDs."

After a local high school football player died in 2000 of sudden cardiac arrest, Gordon coordinated an effort to raise funds to purchase AEDs for all 59 junior high and high schools in Summit County. "We approached a number of different corporations, individuals and hospitals, and after about a year, we were able to raise enough funds," says Gordon. Included in the gift to the county's schools were the AEDs themselves (each typically costs $3,000 to $4,000) and the cost of AED training, which usually requires four hours of instruction, incorporates adult-CPR training and can be administered by a number of organizations, including the AHA and the American Red Cross. AED certification received from the American Red Cross must be renewed annually, while the AHA training requires biannual renewal. "We suggested that 10 to 12 people be trained at each school," says Gordon. "It's a very simple machine, but one that obviously needs to be placed in the right hands."

Depending on the state, a definition of "the right hands" can differ. Currently, each state has some form of Good Samaritan legislation in place, providing legal immunity for a layperson who - provided that individual acts in good faith - assists someone in an emergency situation, such as at the scene of a car accident. Yet because AED technology has only recently become readily available outside the medical community, some organizations are hesitant to ask their employees - should a cardiac emergency arise - to willingly operate a machine that shocks a person with the energy equivalent to that of touching a light socket for three minutes.

A study co-authored by John Spengler and Daniel Connaughton, assistant professors of sports and recreation law at the University of Florida, might help quash such concerns. Their study researched immunity provisions in state legislation for AED users and found that 48 states have such provisions in place, the exceptions being Iowa and Maine. Some states provide immunity only if the AED user acts without expecting receipt of financial compensation, while 22 states require the user to be fully trained and certified by a recognized organization, such as the AHA, the American Red Cross or the National Safety Council. Other variations on AED Good Samaritan legislation include provisions protecting the facility where the device is located and its owners, as well as language protecting organizations responsible for the training of AED users.

"Our stance has been that you create liability problems if you don't have AEDs available," says Eric Green, director of recreation services for Kent State University's Salem, Ohio, campus. Last year, Green surveyed 37 colleges across the country, seeking to find schools that had already implemented AED programs or were planning to do so in the future. Sixty-five percent of the schools surveyed had at least one AED on campus, while 51 percent had installed two or more. Twenty-seven percent were researching the devices, and only 8 percent had no intention of purchasing AEDs. Those that hadn't installed AEDs had an awful lot of questions - for example, what locations are ideal for the placement and distribution of AEDs? "What if the recreation facilities have them, yet your athletics facilities do not?" asks Green. "Does that create a discrepancy of available services and treatment on your campus?"

That's a question Mark Pos, athletic director at Warren Township High School in Gurnee, Ill., hopes his school will have answered in the near future. Taking advantage of a program sponsored by the state of Illinois, Warren Township High purchased four AEDs at half price and installed two each on its campus for freshmen and sophomores and its separate campus for juniors and seniors. On each campus, one unit is centrally located and the other is stored near the athletic facilities.

"We've had some incidents in the Chicagoland area that have drawn attention to the success of AEDs," says Pos, perhaps referring to a June 2001 episode in which a local teenager collapsed and went into cardiac arrest after he was hit in the chest by a pitched baseball. The boy recovered when a police officer jumpstarted his heart with an AED carried in his squad car. "The board of education has been extremely responsive. It makes it a lot easier when the choice is proactive, because the community says, 'Wow, look at this. We're not waiting around until something bad happens.' If for some unforeseen reason we have to use them, they're there."

The staff at Warren Township began the full implementation of its AED program in November, training its key administrative, athletics, maintenance and security staffs with the help of the local fire department. "When a newspaper article was published about us purchasing the AEDs, the next morning we got a phone call from the fire chief offering to train us for nothing," says Pos. "That helps, because if we get 100 to 150 staff members trained, I can go back to the board, give them a dollar amount of how much money we saved on training and ask them to use that money to purchase more AEDs. With that money, I could buy four more and make the buildings really secure."

Campus recreation staff members at the University of Arizona likewise were able to implement a successful AED program through an intercampus partnership. Two AEDs were purchased for the campus recreation department using funds acquired through a grant given to the school's risk-management department. Arizona's campus recreation department then purchased five additional units on its own, installing a unit in each of its recreation centers. In addition to the seven AEDs owned by campus recreation, there are six units located throughout the Arizona campus. "We tried to hit some of the high-traffic areas on campus, like the memorial union and the dance center," says Kim Clark, assistant director of facilities for Arizona's campus recreation department. "We have had some heart attacks in our facilities in the past, so that is one of our reasons for purchasing the AEDs. Also, it seems that a lot of public facilities are headed in this direction. We felt this would be a good course of action to take so that we could provide the best possible care to our patrons, should the situation arise."

College athletic training staff members also see AEDs as an added benefit, not just for student-athletes, but for spectators and referees, as well. "You always have older coaches on the sidelines or parents in the stands," says John Cantwell, cardiovascular consultant for Georgia Tech's athletic teams and team physician for the Atlanta Braves. "Sometimes you're talking about 20 minutes before help gets there. I've used a defibrillator seven times and all seven individuals were successfully resuscitated because we had it right there. They wouldn't have made it otherwise."

Few baseball fans who saw it can forget the tragic sight of National League umpire John McSherry dying of a heart attack on live television during the Cincinnati Reds' home opener in April 1996. While it is uncertain whether the presence of an AED would have saved McSherry's life, a few professional sports teams are also taking precautions. For several years now, the New York Knicks and the Indiana Pacers have had AEDs available for players and other team personnel in case of emergencies, storing the devices either in their locker rooms or training rooms. But this past October, the San Francisco Giants went a step further, installing 24 AEDs in their two-year-old baseball stadium, Pacific Bell Park. The AEDs are located in all areas of the ballpark - near general seating sections, in team clubhouses and in executive team offices - and are strategically placed so that a responder can get an AED to a cardiac victim anywhere in the stadium within two minutes. A 1997 AHA study suggested that sports stadiums are the fourth most common public places where cardiac arrest occurs.

"One of the things we've tried to do is make Pac Bell Park as safe as possible for all our fans," says Staci Slaughter, vice president of public affairs for the Giants. "More than three million people visit the ballpark every year; it's a very busy facility. Fortunately, we haven't had any incidents here since we've opened, but we did have incidents at Candlestick Park in the past."

Private facilities, as well, are implementing AED programs. In October, the International Health, Racquet and Sportsclub Association (IHRSA) signed an agreement with Andover, Mass.-based Philips Medical Systems, manufacturer of the Heartstream FR2 AED, to offer the cardiac emergency-response technology at a reduced rate to its more than 3,600 U.S. member clubs.

As AEDs become more commonplace in athletic facilities, airports, shopping malls and golf course clubhouses, Mary Anne McBurnie and her staff at the University of Washington School of Public Health hope the results of their Public Access Defibrillation Trial will help determine whether publicly accessible AEDs are saving lives or providing false hopes. Funded by a collaboration of the National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute and the AHA, and expected to conclude in March 2003, the Public Access Defibrillation Trial is studying 24 communities throughout the United States and Canada, comparing the response systems of communities with non-medical volunteers who have received advanced cardiac life support and CPR training to the response systems of communities with volunteers trained in AED care. The AEDs in these communities are placed in conspicuous locations, including residential apartment complexes, shopping centers, senior centers, office buildings, sports venues and fitness centers.

"What we want to find out is whether these community-based, non-medical volunteers can successfully use an AED," says McBurnie, who serves as the study's project director. "Does the AED get in the way of a more basic response system? Does the on-site use of an AED delay someone making the 911 call? That would be a major safety issue, since most cardiac events require more than just defibrillation. Our major objective is to see whether the AED improves survival rates over the response system without the AED."

Until the Public Access Defibrillation Trial is complete, it is likely that other organizations - public and private - will deem the potential life-saving ability of the AED reason enough to purchase units for their facilities. James Nevins, physician for the athletic teams at Indiana University, says his department has purchased four AEDs and is in the process of obtaining another. "It's certainly a security blanket," says Nevins. "But my thinking is that if you save one life, it's worthwhile."