Combined high school/community recreation centers can offer their populations distinct benefits, but they must first overcome the inevitable scheduling and programming challenges

If Russ Munch lived in a perfect world, the students at his Pontiac Township (Ill.) High School would have free rein of their own field house with three full basketball courts all day, every day. For example, a February day might see the basketball and volleyball teams run early-morning practices before school. Then, the physical education classes would take over the field house, before giving way to the sports teams for after-school practice. The field house would see action on Saturdays, too, perhaps to accommodate another early morning practice or to play host to a few kids and their pickup games in the afternoon. By week's end, the needs of every Pontiac Township gym rat would be met.

In point of fact, Pontiac Township doesn't have exclusive use of a field house. The facility available to the high school and its 850 students actually belongs to the city and is part of the Pontiac Community Recreation Center. The three-year-old rec center was built on school grounds and shares a common wall with the high school's swimming pool, a building separated from the main campus by a narrow driveway.

As part of an intergovernmental partnership between Pontiac Township High School District 90 and the City of Pontiac, the high school is permitted to use the rec center while the city's parks and recreation department operates and maintains the facility. Munch, Pontiac Township's athletic director, must schedule his school's use of the rec center's field house, two classrooms and aerobics/dance room around the programming needs of the recreation department. It's a give-and-take relationship, but given the alternative - the old gym at the local National Guard Armory - Munch isn't complaining. "It has provided the high school with additional teaching areas," he says of the $3.5 million rec center. "We couldn't have built it on our own and I don't think the city could've built it on its own."

Pontiac Township, a small, rural community of 12,000 residents, is about 100 miles from Chicago and 100 miles from Springfield. "In some of the smaller communities down here, money's very tight. It makes sense to get the most bang for your buck," adds Jerry Hayner, Pontiac's director of parks and recreation. "No, it's not our first choice and no, it's not the high school's, but boy, is it a beautiful facility that's well used."

Given the inevitable scheduling and programming challenges, sharing facilities between high schools and recreation departments may not be the most desirable option for every community. But some municipalities would have it no other way. Cost-saving benefits aside, there are a number of combined high school/community recreation centers that have emerged as true civic centers, reestablishing community ties and attracting people of all generations and backgrounds.

"High schools that my generation attended were like citadels. You went to the high school as a student and you left. No one else had a whole lot of interaction with what was going on at the school, except when you occasionally invited your parents for a play or a game," says John Willi, a principal and director of design research with Dublin, Ohio-based architect Fanning/Howey Associates. "Now there's the concept of the high school as a community cultural center. There's the integration of children of all ages, parents, grandparents and people who don't even have children in school. All of them are able to use this resource."

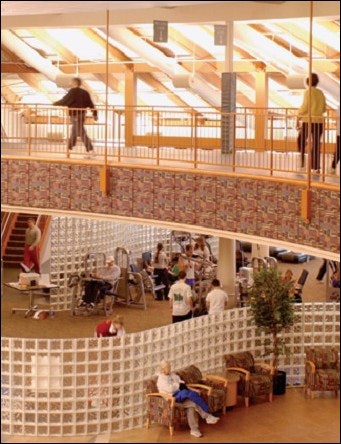

Residents of Medina, Ohio, have just begun to utilize their new community resource - the 540,000square-foot Medina High School/Community Recreation Center, which was designed by Fanning/ Howey. In all, eight public and private partners have a stake in the facility, which was expanded and renovated from an original 178,000 square feet. In addition to what's featured in the new 107,000square-foot recreation center (competition and leisure pools; cardiovascular fitness and strength-training areas; community rooms; a child-care area; a café; a walking/jogging track; basketball, volleyball and tennis courts; and aerobics rooms), a variety of other amenities will be available to the Medina community. They include a 1,200-seat performing arts theater, a hospital wellness center, a public library, a distance-learning center and a cable television studio. "The concept is great," says Michael Davanzo, Medina's athletic director. "It's something our community's needed for a very long time."

It takes a tremendous amount of work to turn the dream of a combined facility into a reality. It's vital that the partnership bonds are forged between a school district and a recreation department long before the going gets tough. Not only do the two entities have to work together to convince constituents of the project's potential cost savings and social value, they also have to place all egos in check and resolve whatever organizational differences may exist. If long-term success is to be achieved, that compromise and cooperation must continue well after the combined facility's doors open for the first time.

The Center of Clayton's operations committee has taken the brunt of that responsibility since the facility opened three years ago. Jointly owned by the City of Clayton, Mo., and the Clayton School District, the 132,500-square-foot recreation center is on district-owned property and is linked to Clayton High School by an elevated bridge and commons area. During the week, the high school has access to the center's two multipurpose gymnasiums, performance gymnasium, competition swimming pool, strength-training room and classrooms.

The Center of Clayton averages roughly 500 users a day. The high school, with an enrollment of more than 800 students, mandates a no-cut policy for its athletic teams, creating an extraordinary demand for court time during the winter season. Over three years, The Center of Clayton's operations committee - made up of representatives from both the high school and recreation department administrations, as well as The Center of Clayton staff - has ironed out the basic scheduling snafus, but still meets biweekly to address potential or actual conflicts. "The Center of Clayton has four full courts. During a school day, one of those courts must be left open for members," says Richard Grawer, Clayton's athletic director, adding that posted signs remind gym users of the policy, with varying success. "We're using all three courts for P.E. classes or after school for practice from 3 to 4:30 p.m., and there's always one court with nobody on it. The kids who don't play after-school sports just want to go down there and recreate. Sometimes that's a problem for our kids. They don't understand all the rules of our agreement."

But the agreement between Clayton High School and The Center of Clayton also has a few unwritten rules - one, in particular, regarding the strength-training room, located adjacent to one of the gymnasiums. Every weekday from 3 to 4:30 p.m., the athletic teams practically set up camp in this area. "The membership has come to know that after school, for about an hour, they probably don't want to use it," says Grawer.

Such implied boundaries don't work for every partnership, though. Despite a preliminary arrangement for the school and rec center to share the strength-training area, Medina athletics officials decided after construction began that they didn't want to take any chances upsetting the rec center's membership. As a result, a 1,300-square-foot storage room was converted into the high school's exclusive strength-training area. "We didn't want the football team to come in from practice in their dirty, stinky clothes and go into the rec facility," says Davanzo. "When the boys do their max lifts, they stand around, yell and chant each other on. The rec center environment wouldn't be conducive to that."

Medina students still use the rec center's cardiovascular fitness area for P.E. classes, which has actually produced an increased level of interaction between the teenagers and older adults. "For the most part, people have been pretty happy with the kids' behavior," says Davanzo. "At times, the phys ed teacher has said they even help patrons with the machines."

A similar camaraderie is developing in Windsor, N.Y., where the 3,000-square-foot Windsor High School Black Knight Fitness Center opened its doors to the public in June 2001. Windsor residents can also use the facility's indoor Olympic-size pool, which opened last February. "They get to see that the kids aren't so bad, and vice versa, maybe adults aren't so bad," says Gary Vail, Windsor's director of physical education and athletics. "It's been a huge positive for our community."

But kids will be kids, and precautions should be taken to ensure the security on the campuses of combined facilities. In its early days, The Center of Clayton occasionally experienced problems with theft or with students ditching class and wandering into the recreation center. Since then, cameras have been installed in strategic locations and a campus supervisor has been stationed to monitor the gateway between the school and the rec center during school hours. "That campus supervisor knows who's coming in and who's coming out," says Grawer. "Kids who violate the rules are punished by being suspended from the center for a week, a month, or even a year if it's something serious."

At the 530,000-square-foot Mason (Ohio) High School and Community Center - in which are shared a 25-meter competition pool, a gymnasium with two hardwood courts and a field house with four multipurpose courts - security measures include more than 90 video cameras, self-locking doors and a swipe-card access system. Doors in shared facility areas, while preventing unauthorized students from passing into the community center and rec center users from intruding into school areas, are programmed to unlock automatically in emergency situations for quick egress.

Mason officials also specified separate locker rooms for the community center and high school. Most of the school's athletic teams continue to use locker rooms located at the old high school. That school - now inhabited by the district's seventh and eighth grades - is next door to the new facility and is home to a 3,200-seat gymnasium, the football/soccer stadium and other sports fields. Locker rooms in the new school, meanwhile, serve the physical education classes and swim teams. "We've got our locker rooms and the center has its aquatics locker rooms for its programs," says Rod Russell, Mason's athletic director. "It's the same with the fitness areas. Our kids have their own locker rooms and the community center has its own spaces. There's no crossover."

There can be crossover, however, with the maintenance of a combined facility. The contract between Medina City Schools and the City of Medina, for example, mandates that Medina's custodial staff maintain both the high school and the recreation center, and that the city pay 50 percent of the maintenance costs for shared areas and 100 percent for the recreation center.

The arrangement is a bit less formal in Pontiac. "If something's needed at the pool, the high school will take care of it. If it's something over here, we'll take care of it," says Hayner. "If their students come in and tear up a classroom, they're going to be responsible for it just like any other group that would use it."

"Many times, maintenance is a combined effort. There's no cut-and-dried way of handling it," says Everett Musser, a principal with Fanning/Howey. "The two entities may try to look at what other facilities have done, and say, 'Well, so-and-so did it this way, so-and-so did it that way,' and combine the two methods and go forward. There isn't a fixed solution for any one facility."

Whatever the formula, most partnerships will run smoothly if the combined facility's maintenance needs and costs are addressed in a timely and evenhanded fashion. As long as groups from Pontiac Township High School leave it clean, Hayner doesn't mind opening up his center's full-service catering kitchen, which doubles as a concessions stand for the high school's outdoor athletic events. During the day, recreation center staff members use the kitchen to serve coffee and refreshments to seniors returning from their morning walk around the high school's track. Come fall Fridays, a gate lifts into the kitchen's exterior wall, exposing a service counter for football games.

"Before, the high school concessions stand was stuck underneath the bleachers. You couldn't see a thing. It was hot and there was no running water," says Hayner. "This kitchen is heated and air-conditioned. We have groups use it all year long. And the bathrooms we built in this facility can be opened and secured, either for use inside the building or from outside."

In years past, such versatility may have been viewed as a bonus. But as budgets tighten, high school and public recreation administrators are increasingly demanding more flexibility from their combined facilities. This is particularly true of mechanical systems. To improve the energy efficiency at Medina, architects specified a central heating/cooling system that divides the facility into zones. "You can have isolation if you want to have events in a certain area and not impact the rest of the facility," says Willi. "You're able to control the temperature in spaces with vastly different needs."

And as more communities are turned on to the cost-saving benefits of combined high school/community recreation centers, there are sure to be more cases of 600-square-foot classrooms sharing the same roof with 24,000-square-foot natatoriums. True, sharing is not for everyone, but community members would be hard-pressed to pass up one-stop facilities where they can learn, recreate, socialize and compete. "The school has a natural connection with the community center," says Jim Voorhis of Voorhis Slone Welsh Crossland Architects, designers of the Mason facility. "Kids can use the recreation facilities after school, and members of the community can use a lot of the school's technologies, programs and classrooms. I don't have any negatives to pass on. It's an extremely positive thing to do."