Children's entertainment centers can be significant revenue producers, but only if they're designed to meet the needs of both children and their parents

That's why more and more recreation facilities, health clubs and wellness centers are offering supervised child-care facilities. Child-care facilities allow centers and clubs to attract a broader market of adults who could not or would not otherwise attend. These child-care facilities are not usually treated as separate attractions or profit centers, but rather as amenities for adult users.

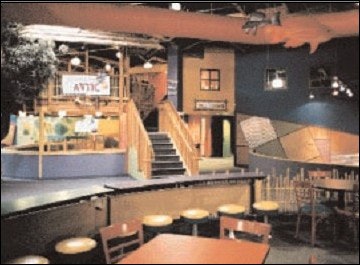

Unlike child care, children's play areas are considered significant revenue producers and are designed to attract an entirely new customer base. They are called children's entertainment or pay-for-play centers, and are sometimes (when they are predominantly based on children learning through play) marketed as children's edutainment centers. Both can collectively be referred to as children's entertainment centers, or CECs.

CECs are typically designed to attract children between the ages of 2 and 10 years old. Most charge an admission fee of $4 to $8, although sometimes they are membership-based. They range in size from about 8,000 square feet to as large as 25,000 square feet. CECs sometimes also include outdoor play areas called adventure play gardens. Not only are CECs destination attractions for children of the facility's regular adult users, but they also attract a whole new group of families whose parents do not use the balance of the center or club.

These facilities are not unique to the recreation and fitness center industry. They are a segment of the family entertainment center industry, which began about 1989. Examples include Discovery Zone, Jungle Jim's Playland and Explorations - facilities targeted to children accompanied by their parents. More are independently owned than are part of a chain. For-profit CECs generate annual attendance from 50,000 to 200,000 children and annual revenues from $600,000 to $4 million.

CECs are commonly found in casinos - most casinos outside of Las Vegas now have them - and retailers such as the Toys " " Us mega-store in Newark, N.J., are adding them. Many fast-food restaurants are adding separate areas with CEC elements, such as McDonald's Playplaces.

Freestanding CECs originally started with soft-contained-play equipment (the maze of plastic tubes, slides and ball pits), a restaurant area and birthday party rooms. However, admission-based CECs that rely on a formula of soft-contained-play as the sole anchor attraction have not remained successful. (Discovery Zone, which recently emerged from Chapter XI Bankruptcy reorganization, followed that formula.) Although soft contained-play is an excellent safe indoor component for children's physical play, younger children require a more diverse variety of play options including construction, imaginative and pretend play. Also, soft-contained-play equipment does not work well in a mixed-age setting, since older children often intimidate and bully younger children. Another problem for for-profit facility owners is that since more fast-food restaurants offer free indoor soft-contained-play, parents are less willing to pay for it.

Existing recreation centers have a competitive advantage when adding a revenue-producing CEC. Recreation centers already have relationships with adult members, and familiarity and trust are very important considerations when parents decide where they'll take their children. CECs can be quickly marketed to existing members, whose loyalty rapidly results in word-of-mouth marketing to new families in the area.

Designing a successful CEC means more than just filling a large room with attractions and play events. Childhood is a complicated part of life. Proper design requires an understanding of how children develop and how their relationship with their parents changes as they grow.

Children are best defined by their developmental skills and needs, which evolve as they grow. Although these changes are gradual and vary from child to child, there are six basic developmental stages that children pass through before they reach their teens: • infant, • older infant to early toddler (we affectionately call them belly babies or wobblers), • older toddlers, • preschoolers, • early grade school (6-9 years old), and • young adolescence (10-12 years old).

CECs should be designed to meet the needs and abilities of all six developmental stages of children (or the first five, if the facility owner intends to target a younger age group), along with the needs and expectations of their parents. For children, this requires offering a variety of attractions and events. With variety, the CEC will engage children; without it, kids will get bored and won't want to return.

The mistake many facility owners have made is focusing on children in grade school or older, while overlooking the needs of younger children and their parents. Doing this cuts out a large segment of families from the potential market. Market studies performed by White Hutchinson in a variety of communities have consistently found that about 45 percent of all families with children 17 years old or younger have at least one child younger than six years old.

Other general considerations for the design and operation of a successful CEC include:

• Infant/Toddler Equipment. Infants and toddlers require tons of gear and a lot of work by parents. CECs need to make this as easy as possible by providing appropriate places for child paraphernalia like car seats, strollers and diaper bags; rest rooms for both sexes that include quality designed diaper-changing areas (not just fold-down tables); areas where a mother can nurse in private; and plenty of high chairs and booster seats. For safety reasons, infants and toddlers need a segregated play area designed to meet their unique developmental needs.

• Rest Rooms. Include child-sized fixtures and specially designed private family rest rooms that one parent can use with children of either gender.

• Cleanliness. McDonald's learned early on that parents won't take their children anywhere that isn't clean and sanitary. CECs need to be designed to make it easy to keep clean, which means materials that are easily cleaned, sanitized and very durable.

• Parental Visibility. Parents need clear visibility of their older children without having to interfere with children's play. Younger children must be able to see and hear their parents during play, and parents feel more secure if they are nearby.

• Child-Centered Design. The design of the CEC environment has a huge impact on children's behavior. Children read environments completely differently than adults. Children feel dwarfed and intimidated by adult-sized environments; most prefer child-scaled environments where they feel competent, so play areas should provide some sense of enclosure and intimacy. Children play longer with greater attention spans and less behavior problems in small-scale environments, and they have more fun.

• Duality of Design. Although children's play areas must be designed for children's needs and preferences, their parents have needs of their own that must also be considered. After all, both parent and child are involved in deciding whether to come back. Adults will see the environment as a background for the activities and judge it on its aesthetics. Children will perceive the environment as part of their experience and try to interact with it in every possible way. A child's idea of beauty is informal and wild rather than formal and ordered - the typical design preference of adults. This duality of often-conflicting needs, wants and aesthetics requires creative design solutions that work from both perspectives.

• Ambiguity. Children's imaginations are virtual-reality machines if you give them the right environment and materials. Play equipment and areas should not be too defined, structured or themed. Except for the youngest of children, the play should be as open-ended and simple as possible so children can use self-initiated discovery and their incredibly active imaginations. Learning through play comes into focus at this point.

• Sense of Place. A holistic and integrated design that is relevant to both children and adults will provide a strong sense of place and identity. This is partially achieved through good space planning and appropriate theming.

• Wayfinding. Children, especially toddlers and preschool children, need a way to "understand" the environment without reading words. They must be able to easily find their way, figure out what the area or event is for, how to use it, any rules that apply, the location of exits and entrances and the boundaries of each play area.

• Outdoor Areas. Research clearly shows that people, and especially children, consistently prefer natural landscapes to constructed environments. Natural outdoor environments reduce stress and are pleasing to adults. Children's play outdoors can be of a higher quality than indoor play - the sensory experiences are different and different standards of play apply. Children can do things outdoors that would be frowned on indoors. They can run, shout, be messy and also experience, interact with and manipulate the environment. Naturalized outdoor play areas are the ideal environment for children's play, and they cost less to build than indoor areas.

• Safety. While designing for safe play is essential, there is a difference between hazards and risk. Safety concerns should not compromise play value. The play environment needs to offer children both challenges and safe risks. Play environments that are too safe are not just boring, but children will often find ways to take risks and find challenges, often in ways that are hazardous. A quality play environment is both safe and challenging.

• Child-Care Standards. If the CEC is going to be used for child-care by unchaperoned children, the facility may need to be designed and operated in compliance with the particular state's child-care laws and regulations. These standards, if they apply, are only minimum standards, and compliance does not necessarily mean that the CEC will be a quality facility.

CECs can generate many types of new business in addition to the walk-in entertainment customer or supervised child-care for members while they use the main recreational facility. The second largest source of attendance and revenue at CECs tends to be from birthday parties. Many CECs host 80 to 120 birthday parties each week. Parties can generate up to 25 percent of total revenue and create what we call "exponential marketing" - one child invites nine other children who enjoy the CEC and want to hold their next birthday party there.

If the CEC has edutainment or learning components, preschool, kindergarten and early grade school field trips can generate substantial weekday day-care business as well as introduce many new children to the CEC. Edutainment components can also be used for regularly scheduled instructional programs and workshops. Other types of potential revenue include play groups with homemakers, after-school care, corporate and institutional picnics, sleepovers and holiday and summer camps.

The commitment to providing high-quality entertainment and learning through play for children is the strength of CECs. That commitment, when connected with an understanding of how to design and operate a CEC that will delight children and their parents, can make the addition of a CEC to a recreation facility an asset for existing customers and users, an attraction to broaden the facility's market and an additional source of revenue.