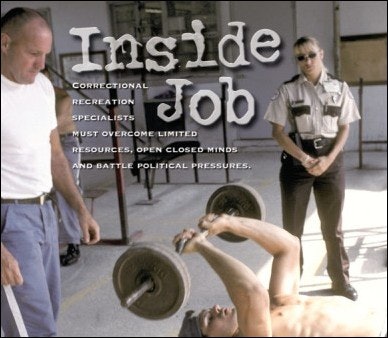

Correctional recreation specialists must overcome limited resources, open closed minds and battle political pressures

Years ago, in what must seem like another life, Bob Tlustos worked as a youth and adult program director at a Nebraska YMCA. He would open the building's doors at 5 a.m., oversee activities all day and then lock up as late as 10 p.m. "I was fried," he says. So Tlustos decided to take a job working in a health club, an experience he found unrewarding.

Today, as prison recreation manager at the Omaha (Neb.) Correctional Center, a medium/minimum security facility that's been his office for the past dozen years, Tlustos and his three-person staff are responsible for keeping almost 600 male prisoners busy with worthwhile activities - anything from reading books and making crafts to lifting weights and shooting hoops. No easy task, to be sure, but somehow Tlustos finds the work satisfying. And because he's only required to put in 40 hours a week (and receives overtime pay, a perk he wasn't entitled to at the Y), he's no longer fried.

But, whereas he once worked with families to build healthy spirits, minds and bodies, in accordance with the Y's mission, Tlustos now puts his own spirit, mind and body at risk by working with incarcerated individuals. "You're not just dealing with third-time DUI offenders," he says, matter-of-factly. "You've got gangsters, drive-by shooters and cold-blooded killers in here. You can't tell what's going on inside their heads, especially with the hardcore guys. They look the same all the time. You can't tell if they're going to talk to you or if they're going to knock you out."

By adopting a broad definition of the term "recreation" to incorporate almost any leisure-time activity (the Federal Bureau of Prisons classifies recreation under its education umbrella), administrators at federal, state and county correctional institutions can try to adapt their programming options to the needs of their own inmate populations - and in some cases, even to the interests of those in the outside world.

In Nashville, Tenn., inmates and the general public alike participate in five-kilometer, half-marathon and full marathon races sponsored annually by the Middle Tennessee Correctional Complex. Inmates and other racers run laps around a ball field lined by razor wire. Last September, the Nashville Striders, a local running club, provided shoes, timing clocks, beverages, T-shirts and medals for the event. "It's the most rewarding thing I've ever done," Striders president Frank Schmidt told the Associated Press.

The so-called Jaunt in the Joint's reliance on makeshift space and contributions from groups like the Striders illustrates how correctional recreation specialists are forced to do more with less - less funding, less equipment and less experience.

Outside the Omaha Correctional Center, weather beaten weights dot a fenced, concrete slab to which equipment is bolted. When equipment breaks, Tlustos says his budget won't allow for a replacement. "When the last plate goes, the weights are gone," he says. Inmates can also participate in outdoor tennis and basketball games, as well as play racquetball and handball against the side of an outdoor wall.

Inside, the aging, tile-floor gymnasium houses a variety of activities, including basketball, volleyball and soccer games, aerobics classes taught via videotape, meetings for on-site veteran and cultural groups, and open-recreation periods. Plus, a four-track recording studio allows prisoners to practice and record music, with all instruments (including an electronic drum kit) plugging into a mixing board that sends sounds through a headphones amplifier so other activities in the gym are not disrupted.

The shortage of funding means recreation specialists must be creative when it comes to programming options. The gymnasium inside the Iowa Medical and Classifications Center, which initially receives every inmate who enters the state's correctional system and eventually winds up permanently housing about 450 males and a handful of females, has a rubber floor and is large enough to house cardiovascular fitness equipment, weight machines, church services, volunteer groups, musical performances and even dog-obedience training courses. Many of those items and programs were funded with revenues from the prison's commissary, but that money has since been earmarked for other sources, according to Ann Sullivan, the center's activity specialist supervisor. So inmates must either make do with what they have, turn to in-house fund-raising (making and selling crafts, for example, or washing staff members' cars) or find alternate activities - like the racquet sport Pickleball, which is similar to paddleball.

"Prisoners need an outlet, and if they don't have one, they'll take their frustrations out on something or someone else," Tlustos says. "Most crimes are committed during someone's leisure time, because people don't know how to use it wisely. They don't pick up a basketball; they pick up a gun and go knock off a convenience store. We want to teach them the skills to do something constructive when they get out of here."

Part of the reason for the disparity between correctional recreation programs lies with the states and counties themselves, which often abide by different training, procedural and political mandates. What's acceptable in one state may not be acceptable in another. Even terminology, such as use of the word "recreation" instead of "fitness," can be the difference between a program's survival and its elimination.

The main reason for the differences, however, seems to be a financial one, as county, state and federal governments struggle with severe budget crises that are resulting in layoffs targeting substance-abuse counselors, mailroom clerks, chaplains and recreation specialists. A major victim of the cutbacks was the National Correctional Recreation Association, a nonprofit training organization that dissolved in 2002 after fiscal slashing reduced or eliminated out-of-state travel for most of its members. Because states differ in their training requirements, the NCRA provided industry-specific training in such areas as security, incident debriefing and gang interaction that recreation specialists couldn't (and, for the most part, still can't) get anywhere else. While most correctional institutions provide their own training, some specialists from facilities that can afford outside training attend annual conferences hosted by the American Correctional Association, the National Recreation and Park Association, the American Therapeutic Recreation Association and the National Intramural-Recreational Sports Association. But the demise of the NCRA has left a void.

At the national level, the Bureau of Prisons (BOP), which operates 104 federal institutions with a $4.4 billion budget, announced in July a 30-day hiring freeze and the potential layoff of some of its 35,000 workers next year. The BOP, which employs approximately 600 recreation specialists, with at least one full-time specialist working in every federal prison, has received only 91 percent of the funding it requires during the past three years, leading to chronic understaffing, according to Phil Glover, president of the American Federation of Government Employees Council of Prison Locals. The agency needs to trim costs by $140 million this year and $300 million in 2005, Glover told The Washington Post in July. Meanwhile, between 1980 and 2004, the number of prisoners the bureau oversees has soared a whopping 577 percent, from 26,000 to 176,000. Since 1999 alone, when inmates numbered 136,000, the population has jumped 29 percent.

"In its ongoing effort to reduce expenditures, the BOP will continue to pursue streamlining, consolidations and other measures to improve the cost efficiency within each of its operations," says BOP public affairs specialist Carla Wilson, "including its recreation programs."

Considering the funding uncertainties, often difficult working environment and little proof of an overwhelming interest in the field, it's no wonder that not a single college or university provides formal training in correctional recreation. "If there is a standalone major anywhere in the United States, I am not aware of it," says Kelly Asmussen, the former recreation manager at the Nebraska State Penitentiary and now a professor of criminal justice at Peru (Neb.) State College. In the mid-'90s, Asmussen tried unsuccessfully to begin a correctional recreation major at Peru State, although there has been some recent discussion of creating a minor in that area of study at the university. "Quite frankly, why would people want to go into the field when all they've heard is how rotten it is?" Asmussen asks. "I went into higher education so I could make an impact on students and talk about the opportunities in correctional recreation. I take my students on tours of the state penitentiary so they can see what it's really like."

All that is required of most correctional recreation specialists is a college degree in recreation or a related field - an ambiguous prerequisite at best, Sullivan says. Indeed, correctional recreation specialists in facilities across the country have backgrounds ranging from business administration and private investigation to athletics and masonry. At the federal level, experience in a related field sometimes even trumps education.

But jobs are tough to find. Despite a reportedly high turnover rate, empty recreation specialist positions are often left unfilled in an effort to save money. There also exists a general lack of understanding about the field. Prisons employ recreation specialists from a variety of backgrounds because, truth be told, individuals who happen to have recreation management or physical education degrees usually don't consider a career in prisons. "This is not how most people view recreation," admits Sullivan, who was Iowa's first female correctional recreation specialist when she began her career 30 years ago. "A lot of people see themselves working in a community setting. Maybe they don't want as many constraints as we have in a prison setting. I've had situations where people have applied for a job here, thought about it and then called and said they didn't want to work here. Plus, I think women sometimes feel uncomfortable, though we have more women in the facilities now than we've ever had."

In the absence of formal education in the field, on-the-job experience remains the best training available, say correctional recreation specialists, who despite their often amicable relationships with inmates have learned how to read body language, when to practice self-restraint and why it's unwise to back an inmate into a corner.

"I would be stupid to say I've never been scared," Asmussen says. "But did I ever show that I was scared? Very, very rarely. The stupidest thing I ever did was go up to the most vicious guy in the place. He was a sex offender, and I'd just had it with his attitude. I took off my glasses, took a pen and drew an 'X' on my forehead. I got in his face and told him to take a dumbbell and hit me on the 'X.' This was in front of all his buddies. He turned around and walked away. Then I went into the bathroom and changed my underwear."

While the University of Florida doesn't offer a correctional recreation curriculum for students, its programs in tourism, recreation and sport management are considered among the best in the country. And for the past eight years, the university has also sponsored a program for employees of the Florida Department of Corrections. In an effort to emphasize wellness education to inmates, the department partnered with the university's College of Health & Human Performance, which developed a 14-week education program for prisoners to be delivered by in-house wellness specialists. In order to become a wellness specialist, however, employees of the state's correctional institutions must undergo an intense weeklong training session at the university, learning how to teach the value of physical activity and cardiovascular fitness, and how to assess an individual's health.

Funded by revenue from prison commissaries and inmates' long-distance phone calls, the Department of Corrections Wellness Education Program strives to prepare the more than 80 percent of Florida inmates who re-enter society to live healthier lives. "We've proven we can cut the average health-care costs of inmates in half - $55 a month vs. $110 a month - compared to other inmates in the state of Florida who aren't part of this program," says Charles Williams, senior associate dean of the University of Florida's College of Health & Human Performance.

In 1997, the university conducted a study comparing the average six-month health-care costs of inmates in the state corrections system who were receiving wellness education to those who weren't. In addition to the health-care cost savings, the study also showed that the average number of infirmary visits during that period was also significantly lower for participants (1.4) than for non-participants (3.5). And according to surveys conducted at the program's conclusion every year, the vast majority of all prisoners in the program strongly agree that their attitudes toward health and fitness have improved. Even learning to do something as simple as calculate a heart rate is considered a major (and valuable) accomplishment for them.

Despite such evidence, there is a contingent of "get tough on crime" proponents who want to limit prison amenities. Many politicians and legislators fall into that category, and Asmussen says it only takes one lawmaker to create some noise about prisoner privileges to force a facility to dramatically reduce its recreation and wellness offerings. "It's just absolutely the most ridiculous political bull," Asmussen says. "A lot of prisoners are good people. They just made dumb, poor decisions. I left the penitentiary because I got burned out hassling with administrators and defending everything I did."

Opponents of prison recreation programs often target weightlifting programs, citing concerns that plates and bars could be used as weapons or escape tools, that bulked-up inmates could intimidate corrections officers and that inmates could intentionally injure themselves while lifting to get out of performing work duties and other tasks.

Supporters of prison weight-lifting programs, on the other hand, argue that the activity serves as a tension reliever, giving prisoners something constructive to do and helping them realize that success requires work.

While weight lifting still goes on within some prison walls, the power-lifting competitions that used to be so prevalent have all but disappeared. Inmates would compete against those at other institutions by exchanging scores via mail or e-mail, but those kinds of competitions are now prohibited in all federal prisons and some lower-level facilities, the result of government orders.

Years ago, Asmussen organized the first maximumsecurity prison bowling league to be sanctioned by the American Bowling Congress, busing 60 inmates to a local alley and teaching them how to bowl and keep score. Eventually, corrections officers and other staff members joined in, and the popular weekly excursions lasted for three years. "I would doubt anybody is doing something similar to that now, given the current climate," Asmussen says. "But it was one of those things that I saw a value in."

"The facility administrators should decide where to make cuts, based on their populations and needs," says Gary Polson, president of Strength Tech Inc., a Stillwater, Okla.-based manufacturer of institutional weight-lifting equipment and accessories, including what it bills as "inmate resistant" foam and vinyl upholstery. "Instead, you've got state legislators who've never been inside a prison making the decisions."

"What our legislators do not realize is that a recreation specialist or a wellness-education specialist can occupy, say, 100 inmates during a recreational activity that may teach them how to live healthier lives - whereas, a corrections officer with a gun may control only about 30 individuals," Williams says. "What's a better use of the state's time and money?"

Asmussen takes the argument even further, claiming that correctional recreation specialists are "the heartbeat" of a prison and valuable for that reason alone. "They can tell you just about everything that's going on in an institution," he says. "They treat inmates like real people, and the inmates feel like they can let down their guard a bit and have some fun. I fought for the right to put an outdoor weight area in for the guys on death row, and they worshipped me. I didn't like them - they killed people. But they treated me with respect, and I treated them with respect. I told them to treat the new weights like a baby, and they wiped them down, put them in racks and covered them up."

"Correctional recreation is kind of like a community-based recreation program," Sullivan says. "We just have more rules and more challenges. Most of these inmates didn't participate in positive activities when they were younger. They've never worked with others on a team. They need guidance, because the vast majority of them don't have social skills. But you're working with a group of people who really appreciate what you're doing."

And because the majority of inmates are eventually going to be released back into society, correctional recreation proponents say the best time to prepare them to live healthier and better lives is when they're part of a captive audience. "We like to think we make a difference in their lives, but you never know," Tlustos says, citing former inmates who have reintegrated themselves into the outside world by becoming personal trainers and sports equipment inventors. "We give them the opportunities to participate. If they do, great. If not, hey, at least it was there for them."

"Like everyone going into any service profession, you'd like to change the world," Sullivan adds. "And then you come to realize that if you can just change a little something about someone's life, that's good, too. Our job is to give them a more positive leisure background than they've had. We want to provide healthy, productive recreational programming. Everything else falls into place after that."