The hospital wellness industry is experiencing unprecedented growth by creating a health club and recreation center hybrid.

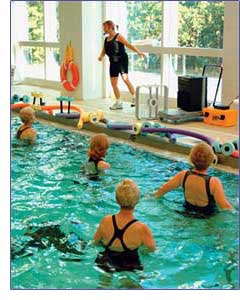

Water aerobics

Water aerobics

It should be good for residents of Peru and its surrounding north-central Illinois communities, too. Like many medical fitness centers today, the North Central Illinois Center for Advanced Rehabilitation and Aquatics will be open to healthy individuals, as well as people suffering or recovering from illness or injury. The Y already enjoys a solid relationship with the hospital, hosting screening clinics and other programs. Now that the two entities have partnered on a larger scale -- IVCH will lease its part of the addition from the YMCA for 20 years - officials are determined to provide services that can't be found at other area medical fitness facilities, health clubs or municipal recreation centers.

Amenities of the three-lane, 25-yard therapy pool will include underwater exercise equipment and whirlpool jets, and the rehab center will incorporate spinal rehabilitation equipment and a device that reduces the vertical effect of gravity in individuals suffering from neurological conditions or severe degenerative disorders, allowing them to walk or ride a stationary bicycle.

"Patients will be able to take advantage of aquatic and land-based rehabilitation services during the same visit," says Jim Scarpaci, physical rehab services director for the hospital. "This is something that can't be done in our area right now. We will have an on-site aquatics program so close that we can step out of one door into the pool. We'll be able to take treatment to a new level in the areas of sports medicine, chronic pain, arthritis and fibromyalgia. People can use equipment free of fear and get cardiovascular exercise they wouldn't be able to get otherwise." Filling voids and niches -- that's been the medical fitness industry's primary focus, particularly in recent years.

"I think we are probably the best-kept secret in the fitness industry," says Cary Wing, executive director of the Richmond, Va.-based Medical Fitness Association, which says the number of medical fitness centers in the United States swelled from 79 in 1985 to 715 in 2004. Likewise, the term "medical fitness center" has evolved to encompass much more than treadmills stationed in the corner of a hospital's psychiatric center. "Some people will join a center and not even know that it's owned by a hospital," Wing continues. "But hospitals want to provide a continuum of care for their communities -- not just sick care, but also well care, or prevention. That's where a medical fitness center comes into play."

With a history dating back at least two decades, these types of facilities are becoming increasingly prominent -- most commonly as freestanding structures affiliated with hospitals. Less than a fifth of all medical fitness centers are still located within the actual confines of a hospital, even though the MFA says 60 percent of all medical fitness centers are owned by one or more hospitals. Another 26 percent are owned by health systems.

Medical fitness facilities average 37,145 square feet in size, with new centers inching closer to 50,000 square feet, and they're most prevalent in the Southeast and upper Midwest. They serve a total of about two million members -- all of whom undergo a health-risk assessment upon joining -- but that number is expected to reach at least three million (using a predicted 1,150 facilities) by 2010.

Worth noting is that almost a quarter of all medical fitness facilities operate as for-profit ventures, with the majority following their affiliated hospital's lead and remaining not-for-profit facilities. Regardless of their designation, most offer such clinical services as weight management, cardiac and pulmonary rehab, physical therapy, and sports and occupational medicine -- alongside cardiovascular and weight-training equipment, personal training programs, group-exercise classes, massage therapy, pro shops, health-education seminars, programming for families and kids, lap pools and whirlpools, indoor tracks and gymnasiums -- at monthly fees comparable to those at health clubs. These programs and services most often attract men and women in their 40s and 50s, a portion of the same demographic that clubs prize most.

Not surprisingly, officials at the International Health, Racquet &Sportsclub Association initially had "grave concerns" about the property tax-exempt status of medical fitness facilities, according to Helen Durkin, IHRSA's director of public policy. But during the intervening eight years, "it hasn't really developed into a huge issue," she says.

"While we aren't always thrilled with the application of the tax law, we find that it is much clearer when it comes to hospitals, and I think hospitals tend to be much more conservative in how they apply the tax law," Durkin continues. "They're more likely to look at the situation and then decide to be a for-profit facility or a for-profit subsidiary."

Wing and other medical fitness professionals stress that their facilities further distinguish themselves from health clubs or municipal recreation centers by integrating hospital services, with an emphasis on the needs of special populations and oversight by a medical director or a medical advisory board. Staff members often hold degrees in exercise physiology and certifications that enable them to understand the protocol affiliated with various special groups, including arthritics, diabetics, cancer patients and victims of cardiac arrest.

According to MFA research, nearly half of all centers have a medical director, but only about a fifth of those medical directors can claim full-time status at a given facility. That perceived shortcoming cost a wellness center in Readington Township, N.J., owned by Flemington's Hunterdon Medical Center, its tax-exempt status earlier this year. In May, the Tax Court of New Jersey concluded that "there was no integration of the care provided at the hospital with the activities and programs at the center, and the center and its operations receive virtually no supervision by the medical staff at the hospital." The court also found that the center's medical director was only obligated to "devote an average of three and one half hours per week" to the facility.

Meanwhile, late last year, Nebraska's Tax Equalization and Review Commission ruled that Alegent Hospital's nonprofit Lakeside Wellness Center in Omaha should lose its tax exemption because it operates more similar to a private club than a charity. Alegent officials appealed to the Nebraska Supreme Court but then dropped their appeal in early 2005. Cindy Alloway, Lakeside Hospital's vice president, issued a statement at the time explaining that "prolonging our involvement in this case would distract us from our healing mission, beyond what we find reasonable."

"There are some hospital-based centers that are not-for-profit that I think should be for-profit, because of the way they're operated," admits Bob Boone, vice president of professional services for FirstHealth of the Carolinas, a three-hospital system serving 14 counties in North Carolina and South Carolina with six nonprofit medical fitness centers. "But if we took our wellness centers and spun them off and made them for-profit businesses, we would lose the integration with the hospital that we currently have, because of federal regulations that would prevent us from talking about individual health histories without having to file a lot of paperwork. The physicians' offices just wouldn't go through the effort to release a patient's specific information to us so we can talk to that person about his or her diabetes, for example. By being a department of the hospital, we can waive all of those requirements."

Durkin is surprised that the New Jersey and Nebraska cases, which didn't generate much news coverage even in the facilities' local communities, got as far as they did. "On a scale of threats, hospital facilities are low on our list," Durkin says. "The fact that there were two cases in the course of six months is unusual. They don't usually go to court."

"Our statement on the for-profit/not-for-profit issue is that every hospital decides whether they're going to open a for-profit or not-for-profit center. It's their choice," Wing says. "As an organization, we don't say that either approach is right or wrong. There's a place for everybody, and we've tried very hard to say, `Look, we all should just be here to serve the community.'"

As with IHRSA, the competition issue doesn't rank high among the concerns of many medical fitness professionals, either. MFA doesn't track local battles, for example, and people like Boone have other, more pressing issues to confront.

FirstHealth's six medical fitness facilities are located in rural areas (such as Pembroke, N.C., home to a large population of diabetes-prone Lumbee Indians) where there are no YMCAs and only one or two health clubs. So while competition might be slim to begin with, Boone is more focused on strengthening relationships with the area's one Gold's Gym branch. Staff members at his facilities are encouraged to refer people who they think might be better served by a traditional fitness model to Gold's -- and Boone says employees there send business his way, too.

Boone also strives to continually make his centers sensitive to their respective environments. "We've tried to match each of our facilities to the needs of its community," he says. A significant part of that strategy, at least for FirstHealth's facilities, means eschewing a clinical environment despite their relationship to a hospital. "Very quickly, our facilities become one of the social centers of the town," Boone says. "An 82-year-old gentleman comes to one of our facilities six days a week, twice a day, for three hours each time -- once in the morning and once in the afternoon. He works out a little bit, he chats, he volunteers, he's become quite a regular, and we miss him if he doesn't show up. It has become part of his life. He's a widower now, and it has replaced the companionship he lost with his wife."

If medical fitness facilities are to become woven even further into the fabric of their communities, Wing says the industry must do a better job of spreading the word. The second annual National Medical Fitness Week, sponsored by MFA and slated for next April 23-28, is already taking shape and is expected to generate more awareness than 2005's low-key event.

Elements of the week will include widespread health fairs and screenings. Some medical fitness center operators already travel deep into their communities to regularly offer free screenings that test cholesterol levels and other health indicators. Such outreach programs often require that patients fill out a health-risk appraisal, which facility administrators then analyze to tailor future programming in specific regions.

Efforts also are under way by MFA to develop more national partnerships with such organizations as the President's Council on Physical Fitness and Sports. Within the past two years, the association has formed alliances with the National Diabetes Education Program to promote prevention of Type 2 diabetes, the International Council on Active Aging to encourage older adults to become and stay physically active, and the Athletic Business Conference and the American College of Sports Medicine to boost industry education efforts.

Moreover, MFA is also nearing completion of a set of standards and guidelines for the medical fitness industry, slated for publication in February. These will include ensuring medical oversight of a facility (via well-defined and adhered-to job descriptions for a physician and/or medical advisory board), providing a risk-assessment of each individual who enters a medical fitness facility, and offering seminars on topics as diverse as medication education and incontinence management.

"These standards were developed with input from facility directors and other people in the industry, so they're all basically following them already," Wing says. "But if you have a new center, these are the things you need to have to really call yourself a medical fitness facility. We think that, down the road, we'll develop an accreditation process. Then all the standards would be required."

Ideally, medical fitness leaders would like to see the industry's presence dramatically expand within the next three years. The form that expansion will take, however, remains to be seen. "To me, the big question is, what role do medical fitness centers play within the continuum of care in the 21st century healthcare system? And what does that model look like?" Boone asks.

"Is it a fully integrated model, like we have here at FirstHealth? Or is it a combination model, with a hospital working with a Y or a commercial facility? My gut feeling is that it doesn't really matter who owns the facility. Hospitals contract out for all kinds of services, so there's no reason they can't contract out for medical-based fitness -- as long as they're striving for the integration that is truly going to create a continuum of care."