Designing a public park requires a lot of time, resources and consultation in order to best meet a community’s wants and needs. Whether the park fulfills a need within a compact footprint in a California neighborhood, sprawls across a 70-acre space that includes a stretch of a natural Colorado creek, or is nestled in a healthy 16 acres of sloped land in the Pacific Northwest, the challenge is to skillfully combine what’s desired, what’s possible and what is affordable into something impactful and lasting.

Architectural and parks professionals in three states share their process, as they embarked on three very different projects that demonstrate the balance of planning successful — and unique — city park spaces.

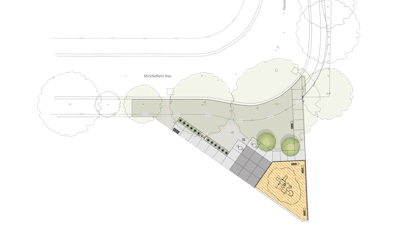

The Luuwit View Park plan for the site in Portland, Ore.Image courtesy of Knot Studio

The Luuwit View Park plan for the site in Portland, Ore.Image courtesy of Knot Studio

A sprawling 70-acre space by the creek

In Colorado Springs, Colo., planners took a mostly underdeveloped park asset and are transforming it into the Norman “Bulldog” Coleman Community Park, a multifaceted outdoor recreational destination and sports-oriented hub.

Colorado Springs city project manager Connie Schmeisser, who also has a background in landscape architecture, says the community is trying to accomplish three things with dozens of acres of green through which Sand Creek runs. “We’re addressing three components in the park,” Schmeisser says. “We have sports needs — we have sports fields we’re trying to replace. It’s also to bring people to Sand Creek, kind of bringing attention back to the waterway. And then the last part is the community park aspect, with the nature and activities that the community wants to see.”

The size of the park, which is exceptionally large, was amassed over time, according to the Coleman Park master plan. The city acquired the park site in 1995 through the land development process, then added to it in 2021, when the city traded via land exchange a 23.5-acre sports complex property it owned for 23.5 acres next to the park site.

Coleman Park is still in its initial phases, with the master planning taking place now, and final design and construction expected between 2023 and 2025. The city hopes to begin construction in 2025 or 2026. City planners have presented a variety of amenities so far for Coleman Park, including a fitness court, terraced seating areas, a shaded tree grove, an educational garden, a picnic area, a large pavilion and more.

While it’s still early in the park-planning lifecycle, the completion of other recent city parks point to a lot of possibilities for amenities in the massive Coleman Park, as well as a substantial price tag, although both elements have yet to be decided, Schmeisser explains.

The ranch-themed 30-acre John Venezia Community Park opened in Colorado Springs in 2017 with a variety of amenities.

“We built Venezia Park, about 30 acres,” Schmeisser says. “It has major artificial turf fields for competitive play and informal play. It has a sprayground. It has walking loops. It has a full tennis court, pickleball sort of complex, a lot of parking. It’s off of arterial roadways, with good access, so it’s a regional draw.”

Venezia Park also includes a large pavilion and picnic area with orchards and parking, a universally accessible playground, a small playground, restrooms, shade shelters, three soccer fields, an in-line hockey rink/basketball court, and a plaza overlooking multi-use fields.

Schmeisser says while the Coleman Park price tag isn’t yet available, a recently reconstructed Colorado Springs park — the 13-acre Panorama Park — cost $8.5 million. Coleman Park’s master planning process is funded through the city and was approved by voters at $247,000, but the full cost of creating the 70-acre park won’t take shape for months, and the city is still working to secure funding.

“We’re doing final geotechnical, getting some analysis, looking at funding opportunities, because the price tag is pretty high,” Schmeisser says. “It’s not high because of anything other than inflation and the number of acres we have to develop.”

The concept plan for small and much-needed Mariposa Park in San Jose, Calif.Image courtesy of San Jose Department of Parks, Recreation and Neighborhood Services

The concept plan for small and much-needed Mariposa Park in San Jose, Calif.Image courtesy of San Jose Department of Parks, Recreation and Neighborhood Services

16 acres with mountain views

A smaller project, the 16-acre Luuwit View Park in Portland, Ore. — inspired by the landscape that includes mountain views of Mount St. Helens and Mount Hood — opened in 2017.

“ ‘Luuwit’ is the Native American name for Mount St. Helens, and the way the park was conceived in terms of the layout, there’s sort of two axes,” Jonathan Beaver, principal and director of design at Portland-based Knot Studio, says. “There’s a north-south axis that is aligned with Mount St. Helens to the north. And then there’s an east-west axis that the shelter sits on. So in Portland, we’re blessed with these amazing mountain views and the park was really built around that idea.”

Portland Parks and Recreation worked with Knot Studio and Skylab Architecture, also in Portland, on the award-winning Luuwit View Park project.

“One thing that’s really significant about Luuwit View Park, and really part of its reason for being, is that it is serving a really underserved area in the City of Portland on the east side,” Beaver says. “We worked really closely with the community, which includes a lot of Spanish-speakers. There’s also quite a Somali immigrant population there.” Beaver says the surrounding community also includes a mix of seniors who have lived in the neighborhood since they built their homes in the ’60s, ’70s and ’80s, as well as a younger generation of people who are moving into those neighborhoods.

The area also had a lack of parks, so as a community park, it would be able to enhance the metro area, Beaver says. “This was bringing in a lot of program that just didn’t exist in the neighborhood,” he explains. “That program includes an inclusive playground, a new soccer field. There’s a teen area with a sports court and skate park. The shelter restroom. There’s an interactive water feature. As part of the project, there’s an off-leash dog area. There’s an amphitheater for summer concerts and other events.”

Luuwit View Park also features a large community garden that serves many, and especially the immigrant communities that were seeking space to garden for sustenance. Passive recreation space for picnicking is in abundance, and a loop trail encircles the park. “That was all developed within the context of managing all the soils on the site, managing stormwater on the site,” Beaver adds. “There are a lot of sustainable features to this park that we worked really hard to achieve as part of the design goals.”

By the time Knot Studio was brought onto the project, a master plan had been done for the park about five years earlier, so one of the duties of Beaver’s team was to analyze that plan and work with the community to make sure the plan and programming worked for all and were still relevant.

“The second part of the master planning effort was really looking at the site itself, and thinking about the relationship of those elements,” Beaver says. “We just saw a lot of room for improvement over the previous master planning work that had been done. So, trying to find relationships, for example, between the shelter, the interactive water feature and the play area that really created a heart to the park. And we found that heart on the axis between these views to Mount Hood and to Mount St. Helens, or Luuwit. That was really the process that we went through with the community in the master planning phase of this — to look at those relationships, present to the community distinct alternatives, and explore what that ultimately should be.”

In the end, it ended up being a hybrid of the schemes that Beaver and the team showed the community.

Beaver says the construction cost for the project was around $8.5 million, with an overall park cost of $11.8 million, which includes consulting fees, staff salaries and permitting, among other expenses. The project was funded by Parks System Development charges, which is revenue from development across the city that’s earmarked to support growth.

Since its opening, Luuwit has proved to be a popular place, which speaks to the design success. “Every time we’ve ever gone out there, I’ve just been completely blown away by how many people are using the space,” Beaver says. “I think it just offers so much for the community in terms of program. And I think there is something really dynamic about the design that we did that makes it feel really interesting for people.”

He says credit goes to Skylab for its innovative shelter design that appears as a sort of structural beacon at the south end of the park. “I think it really helps define the character,” Beaver adds. “The park feels very forward-looking. It doesn’t feel like your typical sort of old-fashioned park. And I think that that feeling that you get when you arrive is really exciting.”

The name for San Jose’s “Mariposa Park” reflects the mural by Morgan Bricca on a highway soundwall adjacent to the park.Photo courtesy of San Jose Parks & Rec

The name for San Jose’s “Mariposa Park” reflects the mural by Morgan Bricca on a highway soundwall adjacent to the park.Photo courtesy of San Jose Parks & Rec

A 0.15-acre pocket park

A few hundred miles south in San Jose, Calif., officials broke ground on the less-than-an-acre Mariposa Park in October 2022. Though the space is a tiny fraction of the footprint of Coleman and Luuwit parks, the need for park space in the neighborhood is exponential.

Sara Sellers, division manager for the Parks, Recreation & Neighborhood Capital Division, says that while the park is small, it’s also unique for the city. “It’s actually not typical. This was really a community vision,” she says. “The community saw this undeveloped patch of land, sort of talking amongst themselves, and leveraged some of the neighborhood groups.”

One of those groups, Latinos United for a New America, or LUNA, acted on their interest and applied for a grant to make the space into a park. Sellers says that LUNA ended up partnering with the San Jose parks department after finding challenges in the bureaucratic process. The land that Mariposa Park is on, once an empty lot, is owned by the California Department of Transportation — known as CalTrans — the state agency that oversees freeways.

“This one is so out of the ordinary, there’s a lot of complicating pieces involved,” Sellers says. “A lot of different grants, a lot of challenges with leases and trying to acquire the property. But the moral of the story is the community was so dedicated, they found this path forward that eventually they ended up joining efforts with the city.”

CalTrans provided $500,000 through its Clean California State Beautification Program to fund the park along with an initial grant of $250,000 from the Open Space Authority, which works to conserve the natural environment. Sellers says the city also provided $1.12 million in funding as of late July — however, the price won’t be final until the project is completed.

“This one doesn’t follow our typical master planning process,” Sellers admits. “Normally, we have it pretty structured, we meet with the community a minimum of three times. This one was really already packaged. The community had a vision, and the city essentially just helped them implement it and get it to the finish line.”

The Mariposa Park moniker stems from a mural by a local artist on the adjacent highway soundwall, “El Sueño de la Mariposa,” which translates to “the butterfly’s dream.”

The little park packs in a butterfly-themed playground, seasonal waterplay sandbox, table and bench seating, landscaping, irrigation and an open area for gatherings.

Sellers says Mariposa Park is in a park-deficient area, and its creation follows in the philosophy of the Trust for Public Land, a group that calls on mayors to make park space available for residents of U.S. cities within a 10-minute walk from home. San Jose also uses data to determine areas in need. “It’s really trying to hone in on not just where the park deficiencies are, but where there’s park deficiencies and the more underserved community needs,” Sellers explains.

Mariposa Park is still wrapping up construction and is expected to open before fall 2023.

Luuwit View Park features a soccer field, a basketball court, accessible play and picnic areas, community gardens, a fenced off-leash dog area, and foot and bike paths with expansive views – including a majestic vista of Mt. St. Helens.Photo by Craig Alness

Luuwit View Park features a soccer field, a basketball court, accessible play and picnic areas, community gardens, a fenced off-leash dog area, and foot and bike paths with expansive views – including a majestic vista of Mt. St. Helens.Photo by Craig Alness

While size, needs and locale will vary considerably depending on where a park is to be sited, each project is aimed at benefitting the many. That’s what is satisfying about parks planning work, Sellers says.

“It’s seeing that your work actually improves the lives of others,” she says. “Because we are really trying hard to get into neighborhoods that have felt like they don’t have a voice and they haven’t been heard. We’re trying to make bridges and better relationships and figure out how a park can not only provide open space, but how a park can maybe increase social interactions, provide cooling for the city in urban heat island areas, and tot lots that could actually help with early childhood development.”

Beaver of Knot Studios says identifying a park project that works is as simple as observing it in passing. “You can tell when you go back to projects whether they’re successful. For one thing, you just see a lot of people using the park. I’ve also noticed there just isn’t a lot of vandalism at the park. There really is a lot of community pride around it. And I think that’s often an indication that it’s a space that’s really well loved and protected by the community that surrounds it.”