Salt Lake County officials join forces to pass an innovative tax.

It's harvest time in Salt Lake County, Utah. At Wheeler Historic Farm in South Cottonwood Regional Park, visitors are cutting hay and picking corn, some of which will be turned into feed for the park's resident farm animals. Offering a glimpse into life on a pioneer farm, the park has attracted citizens for more than two decades.

Now, a new master plan has given the park, among other things, a more welcoming entry, additional parking and an activity barn that can be rented for special occasions. And as before, while farmhands do the majority of the work, community members can lend a hand, or even harvest their own plot in the community garden every fall.

But it's not just crops that are being harvested this year. The county is also reaping the rewards brought by a special tax imposed to benefit the county's zoo, the arts and parks. South Cottonwood Regional Park is just one of 12 major projects completed in the past two years as a result of the so-called ZAP tax.

"We would have been able to accomplish maybe 10 percent of this with the county's general fund," says Bruce Henderson, recreation section manager for Salt Lake County Parks and Recreation. "If we hadn't had the ZAP tax, most of this wouldn't have been feasible."

Best of all for the community, the tax has had a relatively small impact on residents, only requiring a 0.1 percent increase in sales tax for 10 years. For every $10 spent in the county, a resident contributes a penny to a general fund. When distributed, 12.5 percent of the windfall goes toward the zoo, 30 percent to parks and recreation and 57.5 percent to the arts. Why the imbalance? The tax began as an arts council initiative in 1994. However, when the arts community attempted to pass a tax to support just the symphony, opera and ballet, it failed.

"The general electorate felt that it would just serve the elite few, or some people who lived near the arts facilities," Henderson says. "So, the people who were behind the project decided to tie it to something that appealed more to the general electorate."

The proposal was revised to include parks and recreation projects, local botanical and zoological entities and cultural programming. Thanks to this alteration and an aggressive campaign, the tax passed in 1996, netting $13 million the first year. The key, says Henderson, was joining forces. Twenty-five years ago, when the county last tried to pass a tax for recreation alone, it too failed. "When you are able to diversify the benefits of the tax, combining the zoos and recreation facilities with the arts, you've pretty well touched just about every portion of the community," Henderson says. "I think that's what sold it."

Over 10 years, the tax is expected to raise $50 million for parks and recreation, which will repay the $50 million in general obligation bonds approved by voters in 1997 so that construction could begin immediately.

"We got all the money up front, which enabled us to build everything at once," says Desiree Beaudry, research and planning analyst for Salt Lake County Parks and Recreation. "This means everybody gets served at the same time, and it saved us money, since the cost of building is only going to go up." The funding doesn't cover operations, but the county intends to use a combination of user fees and general funds to continue to support the facilities. While many of the facilities are nearly self-sufficient, Wheeler Historic Farm has always struggled, and only supports about 25 percent of its operations. Viewed collectively, it is estimated that the new projects will be about 70 percent selfsufficient through user fees.

One of the more innovative, and most recently completed, projects was achieved through a partnership with the Lions Club of Holladay. Supported A $500,000 donation from the Lions Club, the county created Holladay Lions Park specifically for people with disabilities.

Along with accessible playground equipment and paved paths, the park features a sensory garden with special stations where sightimpaired individuals can work the soil, and elevated plantings so those in wheelchairs can more easily smell the plants.

A beeper baseball field, which features bases and balls with beepers, is included for the sight impaired, as well. Adjacent to the park is a separate project, the 36,000-square-foot Holladay Lions Fitness and Recreation Center, which, along with an aerobics room, fitness room and offices, offers a lap and leisure pool with a transfer wall, ramps and other features to ease accessibility.

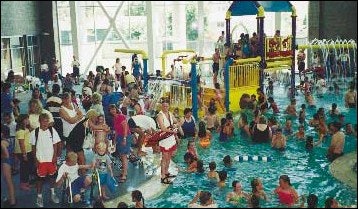

The tax also funded an 80,000-squarefoot equestrian park in urban Salt Lake City, three recreation centers, a swimming pool, an aquatic center, an ice center, a four-diamond softball complex and a seven-mile parkway addition. Prior to the tax, the newest facility in the county dated from 1972, and whatever facilities the county had were fairly concentrated on the more-developed east side.

"The east side has been around longer, so of course we built the facilities where the people were," Beaudry says. "When the population moved west, they were deficient in centers. Now things are really nicely balanced."

By dispersing its benefits over widespread areas and among diverse constituents, Henderson says, the ZAP tax has found nothing but support. In fact, even though the tax doesn't expire until 2007, it has been so popular that Salt Lake County residents are already discussing renewing it for another 10 years.