The NBA May Have No Legal Defense in its Pursuit of an Age-Eligibility Standard

Four of the top eight picks in the 2001 National Basketball Association draft entered the professional ranks directly from high school, completely bypassing collegiate careers. Those four players were among six high school athletes who declared themselves eligible for this year's draft, joining 13 others who have entered the draft directly from high school since 1995. All but three of those 19 players were selected in the draft by NBA teams and many have gone on to have successful professional careers without the seasoning that college can provide, both on and off the basketball court. However, the NBA has received a great deal of negative publicity from the media, as well as the league's fans, for its policy of allowing players to enter the draft at such a young age.

Critics allege that the NBA's draft policy (the league currently allows anyone whose high school class has graduated to become eligible for the draft) exploits young men who are not physically or mentally prepared for the wealth and lifestyle associated with playing professional basketball. Detractors also claim that while a few players entering the league directly from high school (Kobe Bryant, Kevin Garnett and Tracy McGrady) have become superstars without the benefit of collegiate experience, many others have failed to succeed and have found themselves out of work by their mid-20s and ill-prepared for a career away from the sport.

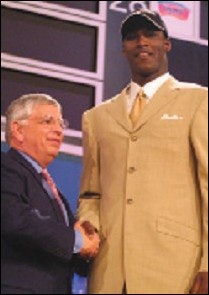

While the merit of these claims is a matter of some debate, NBA Commissioner David Stern seems poised to take action on the subject. On several occasions during the past season, Stern discussed creating a minimum-age standard of 20 in order to be eligible for the NBA draft. Stern's proposal has support among fans, the media, current NBA players and executives, and supporters of college basketball, including all-star center and NBA Players Association executive committee member Alonzo Mourning and former Georgetown University men's basketball coach John Thompson. (As Thompson recently remarked, "A kid can drive a car when he's 13 years old, but we don't permit him to do that.")

Unfortunately for Stern, Billy Hunter, executive director of the NBA Players Association, is not convinced. "If your ambition is to play professional sports and you've demonstrated the skill and ability," Hunter asks, "why should the door be closed to you?"

The door, in fact, was closed once before. Prior to 1971, a player could not be drafted by an NBA team until four years had passed since the athlete's graduation from high school. The American Basketball Association, a league in competition with the NBA at the time, had a similar age-eligibility rule. However, the ABA allowed exceptions to the rule for athletes who could demonstrate a financial hardship. In 1971, Spencer Haywood utilized the ABA's hardship exemption and joined the league after a two-year collegiate career.

A year later, after Haywood won the ABA's Rookie of the Year and Most Valuable Player awards, Haywood claimed his agent had fraudulently misrepresented him in negotiating his contract the previous year with the ABA's Denver Rockets and, as a result, rescinded his contract with the team. Haywood subsequently signed with the NBA's Seattle Supersonics despite being one year shy of meeting the NBA's age-eligibility rule. After the league disallowed his contract with Seattle, Haywood successfully sued the NBA under the Sherman Antitrust Act.

Following the league's legal setback in Haywood v. NBA [401 U.S. 1204 (1971)], the NBA followed the ABA's lead and created a hardship exception to its own age-eligibility rule. In 1976, the NBA adopted its current rule, allowing any high school graduate to enter the league through the draft or free agency (if the player is not drafted by any team) upon renouncing his college eligibility.

The legal ramifications of creating a new age-eligibility standard of 20 years old are somewhat complicated. Age-eligibility rules may be subject to legal challenge under either antitrust law, as was the case with Haywood, or labor law. Antitrust law, governed by the Sherman Antitrust Act of 1890, was created in order to prevent monopolization and other restraints of free trade. On the other hand, labor law, regulated by the Clayton Act of 1914, serves to protect labor-management agreements, such as the NBA's collective bargaining agreement with its players, from scrutiny under antitrust law. (Whereas an agreement between management and labor might sometimes be labeled as a restraint of trade and thereby not permissible under the Sherman Act, the Clayton Act provides this type of collective-bargaining activity with immunity from antitrust law.)

If the NBA could come to an agreement with the Players Association on Stern's proposed age-eligibility rule and include the rule in the next collective bargaining agreement, the rule would likely be immune from antitrust law through the Clayton Act's non-statutory labor exemption. This is where Hunter's stance on the age-eligibility issue is troublesome for Stern and the NBA. If the NBA could not persuade the Players Association to include Stern's proposed rule and instead decided to unilaterally implement the rule, the rule would likely fail to meet the requirements needed to show that it should receive the non-statutory labor exemption and could therefore be subject to legal challenge under the Sherman Act.

Based on a number of cases in the past three decades, the U.S. Supreme Court has created a Rule of Reason in order to analyze alleged violations of antitrust law under the Sherman Act. The Rule of Reason balances the benefits to competition of an activity against its anti-competitive aspects. If Stern's proposed rule were unilaterally implemented and subsequently challenged under antitrust law, the NBA might attempt to justify the rule by arguing that the rule protects young athletes from the physical and mental rigors of professional basketball and that it encourages athletes to pursue a college education.

While there may be merit to these arguments, they would likely be rejected by the courts. In National Society of Professional Engineers v. United States [435 U.S. 679 (1978)], the U.S. Supreme Court limited the analysis of the Rule of Reason to economic issues, not policy issues. Based on this decision, the NBA would need to convince the courts that players under the age of 20, despite their talent and potential, depress the league's level of play because of their lack of experience, and that this lower level of play would lead to reduced television rights fees and decreased attendance, forcing NBA teams to increase ticket prices in order to maintain their revenue levels. Such an argument, obviously, is quite speculative, and if it failed (as seems likely), the NBA's violation of the Sherman Act would force it to pay triple damages to the plaintiffs.

Obtaining the support of the Players Association is certainly a key issue in Stern's implementation of an age-eligibility standard that will survive legal scrutiny. What will be interesting to see in the next few years (the NBA's current collective bargaining agreement expires after the 2003-04 season) is whether Hunter's statements are truly indicative of his fundamental beliefs on the issue or part of a strategy to use the issue as a bargaining chip at the negotiating table. Either way, Hunter is perhaps the most important player in determining the success of the proposed rule, which would not only affect the future of professional basketball, but also play an important part in shaping the future of the college game.