Amenities have become increasingly critical elements to collegiate and professional sports venues laboring to turn a profit

In 1977, fans attending a collegiate or professional sporting event were doing so for one reason and one reason only: to watch the game. This statement may sound oversimplified, but the fact is that over the course of the past 25 years, the live sports experience has gradually taken a backseat role to an expanding array of diversions available at arenas, ballparks and stadiums everywhere.

Fans these days are attracted to facilities that sparkle with the latest dining, entertainment, seating and retail offerings, spending $26.17 billion at American sports venues last year alone. Increasingly, collegiate and professional teams racing to get their share of this revenue are investing millions in new construction, renovation and expansion efforts, outfitting their home arenas and stadiums with the most luxurious finishes, premium amenities and first-class seating options that, at times, belie their original purpose.

Changes in at least one area of sports venues have arguably improved the experience for fans: the concessions stand, where they have gradually encountered shorter lines and in many cases, more expedient service. Patrons have also seen the traditional menu at concessions stands become not so traditional. While the old standbys of hot dogs, popcorn and cold beers might have been plenty satisfying for hungry sports fans two and a half decades ago, now their tastes are more discriminating, as arenas and stadiums serve up a continually expanding variety of food and beverage options, including ethnic cuisine, vegetarian dishes, gourmet desserts and top-shelf alcoholic beverages. "It's tough for a concessionaire to go in there and sell a generic pizza versus a national or regional brand that people really know," says Chris Bigelow, president of The Bigelow Companies, a Kansas City-based food-service design and management consultant. "It's a lot different from how it was 10 to 15 years ago."

Many popular (and successful) offerings at concessions stands today are simply more expensive variations of the originals (Italian sausages instead of hot dogs, garlic fries instead of French fries), while some of the highly specialized items have yet to make a significant profit for concessionaires. "There's always going to be things like sushi that get a lot of press, but don't produce the volume that some of these other items do," says Bigelow, who maintains that success at the concessions stand still depends on volume sales. "But it helps fans realize that they need to look at the menu and that there's more than just hot dogs, popcorn and nachos."

Just as the level of fans' sophistication continues to increase, so does the amount of time they spend at sports venues. Halls of fame and kids' arcades are among the attractions that draw fans to arenas and stadiums sometimes hours before gametime. Accordingly, teams must be prepared to accommodate their patrons' appetites. "Once you get them there, they're going to eat more," says Bigelow. "But again, fans are expecting more; they're not going to be satisfied with just a snack. They're thinking, 'If I'm going to spend four hours in this building, I want to sit down and get a meal.' So the offering has to be there. You have to provide tables and chairs."

Many observers point to Toronto's Skydome, which opened in 1989, as the first sports venue to introduce full-service dining options. The stadium also incorporated components entirely unrelated to the sports experience, including a hotel, a health club and a television production studio - innovations that were highly regarded at the time.

In recent years, however, an even greater number of non-game-related components have made their way into sports venues that do not receive the same overwhelming stamp of approval. "I think parks these days are really loaded up with too many attractions," says John Pastier, a Seattle-based architecture critic and longtime ballpark design consultant. He lists children's play zones, booming audio systems and outfield gimmicks such as swimming pools and water fountains among the most distracting elements in more recently constructed baseball stadiums. "It's a double-edged sword," says Pastier. "Kiddie parks may make things better for the parents in the short run if they've got a screaming kid who wants to go home. It is better than leaving the game entirely. Meanwhile, they dilute the experience and prevent parents from seeing the game."

The consensus among sports team executives suggests that despite the risks of introducing elements that might serve as a distraction to some fans, they are necessary to draw those individuals who aren't as concerned about the score or which team has the ball.

"Have you been to Bank One Ballpark? It's like an adult Disneyland. There's so much to do that if you miss the game, you can still go home happy," says Ray Artigue, senior vice president of marketing communications for the Phoenix Suns, who play in America West Arena, two blocks from the home stadium of the Arizona Diamondbacks. Artigue contends that providing additional entertainment options is necessary for teams to stay competitive in the battle for patron dollars - a struggle that, as of late, the Suns have found to be increasingly difficult in their marketplace.

Phoenix is experiencing a boom in sports facility construction that is due to leave 10-year-old America West Arena as the oldest professional sports venue in the area. It began with the 1998 addition of the Diamondbacks and Bank One Ballpark to the downtown landscape, and was followed up by the April groundbreaking for the Phoenix Coyotes' new arena in Glendale, 20 miles west of downtown Phoenix. The NHL team, which will begin play in its new home in fall 2003, has been a tenant of America West Arena since the 1996-97 season. The NFL's Arizona Cardinals, the fourth professional sports franchise in the city, also hope to begin construction on a new $350 million home within a year.

In response, the Suns have undertaken a three-phase, $39 million renovation project at America West Arena, beginning with a new club-level lounge and improvements in the concourses and concessions areas. The final two phases are of a much larger scale and will give the arena a new exterior façade on its north and east sides, including a partially enclosed, 60,000-square-foot entertainment and dining paseo on the east. Inside and out, the updates are designed to give the facility a much sleeker appearance. "It's all about keeping up with the Joneses," says Artigue. "It's about expanding the overall experience and the value, and hopefully, it's a motivating factor in getting people to come and enjoy a game in person, as opposed to watching it from their couch at home."

As comfortable as some seats are in sports venues these days, it could almost be said that catching a game there is like watching one at home. Today's luxury suites (which can seat anywhere from 12 to 40 people, on average) and club-seating sections offer guests catered meals, top-shelf alcoholic beverages, access to exclusive social lounges or clubs (even during non-event times in some venues), private rest rooms and privileged parking passes. However, to enjoy these types of amenities, fans must either carry some corporate clout or be prepared to pay some pretty exorbitant prices.

According to figures published by Revenues From Sports Venues, a Milwaukee-based sports research company, the yearly cost for a luxury suite in a Major League Baseball stadium ranges from $81,730 to $173,073. NFL suites are comparable, beginning at $55,488 and topping out at $181,097. Skyboxes at both NBA and NHL arenas, meanwhile, start at approximately $110,000 and go as high as $210,000.

Club seats, while not nearly as expensive, can still empty fans' wallets in a hurry. Among the "big four" professional sports, licenses for these seats often require a "contribution" of anywhere from $2,000 to nearly $8,000 a year - which, of course, is in addition to the cost of season tickets.

The luxury-accommodations craze has barreled down to the collegiate level at a breakneck pace. Since 1995, 13 of the 25 largest college football stadiums in the country have either added or significantly updated luxury-seating areas. Of those 13 facilities, nine have been renovated within the past three years, and two others are slated to be updated again beginning next year. Some of the more recently constructed basketball arenas on college campuses - Texas Tech University's United Spirit Arena, the University of Wisconsin's Kohl Center and Ohio State University's Jerome Schottenstein Center among them - all feature private suites. Yearly leases for suites in college sports venues begin at around $20,000 and can reach as high as $60,000, as at the University of Alabama, where sales from suites in Bryant-Denny Stadium netted the football program around $3 million in 2001.

Because of the potential to generate millions of dollars, a number of collegiate athletic departments are eager to add luxury suites to their older stadiums and arenas. However, for others, it is a difficult choice, as the integration of premium seating options that will most likely be occupied by wealthy alumni and corporate sponsors can alienate student fans and plunge department budgets deep into debt.

A $50 million renovation project underway at the University of Florida's Ben Hill Griffin Stadium at Florida Field, for example, will create a new press box, 28 luxury suites and 2,900 club seats, as well as triple the size of an existing theater-style, club-seating area. Despite the fact that the new seating is expected to bring in more than $6 million a year, the athletic department won't be able to retire bonds used to fund the project for another 30 years.

The 2000 addition of 78 luxury suites to the University of Tennessee's Neyland Stadium cost the school $18.9 million, or approximately $242,000 per suite. This figure dwarfs the $30,000 that each suite nets the athletic department annually.

"I'm concerned about institutions overspending," NCAA President Cedric Dempsey told Florida Today last August. "I certainly realize at times some of the facilities need to be improved. But at the same time, there are some facilities that have maybe gone beyond improving."

These concerns have made their way from NCAA headquarters and onto a number of college campuses nationwide. One school hesitant to jump on the luxury seating bandwagon is Indiana University. Officials there laud the school's basketball arena, Assembly Hall, for providing fans an original sports experience, complete with raucous crowds and reverberating floors - largely thanks to the close proximity of seating in its lower bowl to the arena floor. Other than having its court surface replaced and additional floor-level seating installed in 1995, the 17,257-seat facility has not undergone a major renovation in its 30 years of operation.

Should school officials deem one necessary, however, they will be careful not to disrupt an environment that, according to Jeff Fantner, Indiana's assistant athletic director for media relations, is a central reason for the success of the men's basketball program. "The tradition of this building has a lot to do with it," he says. "We are always exploring ways to provide the best possible experience for fans, whether it's through better sight lines or seat locations. To say that we'll never make any changes wouldn't be true, but we're definitely being cautious as we explore those options."

Similar caution was exercised by officials at the University of Kentucky with the 1999 expansion of Commonwealth Stadium, which opened in 1973. As part of the stadium's update, two new video scoreboards were installed in each end zone, a move some of the school's athletic officials were reluctant to make.

"We went from not having any videoboards to having two," says Russ Pear, an associate athletic director at Kentucky. "Our former athletic director had a very conservative opinion about it. He felt college athletics had changed considerably for the worse, and we had to convince him that the videoboards could be part of the experience. People like to see themselves on screen; they like to see replays."

Besides replacing 7,000 semi-permanent wood bleacher seats in the end zones with 18,000 permanent steel and aluminum bleachers, and adding concessions and rest-room facilities underneath the new sections, the expansion at Commonwealth Stadium also added 40 private suites, 10 in each corner.

"We knew there was a market for suites, but our goals remain fan-based," says Pear, who maintains that the desire to add suites was secondary to a more significant need to address the stadium's lack of sufficient concessions and rest-room facilities. "We feel it's very important for our students to have a good experience because those individuals make up our donor base of the future," says Pear. "If we're not trying to accommodate those fans at this point, it's going to be difficult 15 years down the road when we need them to help generate income."

Todd Hunt, facility director of Mississippi State University's 27-year-old Humphrey Coliseum, agrees, but for different reasons. "You have to make sure that the students are close to the action and are able to get the team pumped up," he says. "A lot of times, you'll find that your suite holders are not exactly the most vocal fans. While you certainly need both groups, you don't want to take away from the home-court advantage that teams can enjoy with a rowdy crowd."

Maintaining this experience was the goal of the 1998 renovation of Humphrey Coliseum. By removing the inner concourse and realigning seats in the lower bowl, enough space was cleared for 1,000 permanent chair-back seats to be added at courtside. While the renovation pushed Humphrey's capacity to 10,500, it is still among the smallest basketball arenas in the Southeastern Conference.

Overall, though, Hunt says that the atmosphere inside the arena has benefited from the renovation. Meanwhile, the situation underneath the stands has become worse. "We increased our capacity, but we probably decreased our user-friendliness," he says, blaming the elimination of Humphrey's lower concourse. Both the upper and lower bowls now share the upper concourse. "It can get a little crowded out there. People are still able to move around; it's just a little tighter than you would like it to be. And we certainly don't have any space to set up extra things like kiosks or interactive games."

It's unlikely operators of newer sports venues will ever be heard making the same complaint. "Today's facilities have immense concourses for people to move around," says Pastier, adding a complaint of his own. "But then the teams immediately fill these concourses with portable vending stations. They place them in such a way that they jam up all over again, as if they didn't build a large enough concourse to begin with."

Indeed, kiosks, tables and stands selling everything from sportswear to bottled water is a trend that Pastier says is not accidental. "Teams want to slow down traffic," he says. "If you go straight to your seat, you might not stop and part with your money. But if you're standing, you might think, 'I'm not going anywhere, I might as well go buy that.' "

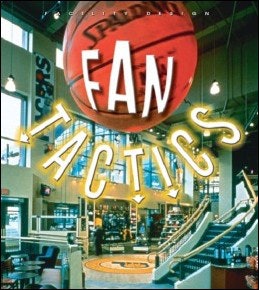

It truly has become tougher for fans to turn down such retail opportunities - after all, they're being presented with a much greater variety of souvenirs and novelties than was offered in arenas and stadiums of the '70s. Retail operations that might have begun as small stands selling T-shirts and programs have since grown to become large team shops. Other kinds of specialty stores - many of them non-sports-related - have also made their way into sports venues, enticing shopaholic fans to journey to arenas and stadiums more often, even during non-event times.

Officials at America West Arena believe their investment in the retail plaza addition there will help generate increased consumer traffic. "We've certainly seen a development here in Phoenix: The center of the downtown entertainment district has shifted south and now focuses around the ballpark and America West Arena," says Paige Peterson, general manager of Sports and Entertainment Services, the facility's management company. "We believe that trend will continue, and providing fans with retail opportunities will only help."

Several cities besides Phoenix have recently taken to centralizing their entertainment districts around major sports venues. For example, in 1999, Nationwide Arena opened in downtown Columbus, Ohio. Besides serving as the home of the NHL's Blue Jackets, the arena anchors the 95-acre "Arena District," a revitalized neighborhood featuring hotels, theaters, restaurants and bars, as well as commercial, residential and retail space.

Next month, Ford Field is slated to open at the edge of downtown Detroit, replacing the Silverdome, located 30 miles away in the suburb of Pontiac, as the home of the NFL's Lions. Joining the recently opened Comerica Park, the home venue of Major League Baseball's Tigers, in downtown Detroit, Ford Field is expected to spark a major revitalization of the area in preparation for the city's hosting of the 2006 Super Bowl.

These facilities are among many built within the past 10 years that have continued a trend begun by Baltimore's Oriole Park at Camden Yards. This ballpark and subsequent major-league parks built in Cleveland and Denver are often credited with pioneering a return of the sports venue to urban settings and reversing a decades-old practice of arena and stadium construction in suburban or even fairly remote locations.

Camden Yards was famously built atop an old railyard at the outskirts of downtown Baltimore, and designers incorporated an adjacent city street and warehouse into the ballpark. The street was closed to vehicular traffic and is now lined by restaurants and concessions stands, and the warehouse holds the Orioles' team shop and administrative offices. As a result, the stadium provides fans with a visible connection to Baltimore's industrial history.

There are indications that this attribute - a venue's integration into its surrounding environment - will become an even greater focus of future sports facility design. While many fans don't mind walking a few blocks to the game from where they've parked, anything longer than that often proves to be a nuisance to them. This is especially true when during their stroll, they have to experience the unpleasant odors of an industrial park or the noisy rumblings of a busy highway.

Two current stadium projects have addressed this issue and perhaps will enhance the efforts of previously constructed urban sports venues. The first is Seahawks Stadium, the new home of the NFL's Seattle Seahawks, which is slated to open next month. Replacing the demolished Kingdome (which opened in 1976), the 72,000-seat facility is situated directly adjacent to Seattle's historic Pioneer Square, one of the city's premier entertainment and cultural districts. A tree-lined plaza on Seahawks Stadium's open north end connects to Pioneer Square and provides fans with ample gathering space before and after the game. Rising above this plaza is a broad, grand staircase that affords fans views from their seats to this charming neighborhood, as well as the city skyline and Olympic Mountains behind it.

Seahawks Stadium also features some of the latest innovations in luxury accommodations, boasting 7,000 extra-wide club seats and 82 luxury suites, including the NFL's first field-level suites. Twelve "Red Zone" suites are located in the north end zone, just four feet above the playing field.

The second project, and perhaps more significant to the evolution of sports facility design, is the as-yet unnamed "A Ballpark for San Diego," due to become the new home of the San Diego Padres by Opening Day 2004. The ballpark, similar to Nationwide Arena, is designed to anchor a 26-block redevelopment district, potentially bringing millions of dollars to downtown San Diego through the addition of hotels, offices, retail and residential components. The project is of such a large scale that an urban planner has been commissioned, in addition to three architecture firms.

Reminiscent of Camden Yards, the irregularly shaped San Diego ballpark will also integrate a historic brick building into its design. The 92-year-old, 80-foot-tall Western Metal Supply Co. building will actually border the playing field, and one of its corners will be used to determine the difference between fair and foul territory along the third-base line. Balconies attached to the building's large windows will be used as five party suites, available for single-game group sales.

Despite its commercial appeal, the ballpark is designed to reflect the playful spirit of San Diego's outdoors-loving residents. A fully landscaped park will extend beyond the stadium's centerfield wall, allowing fans there to picnic, socialize and even catch a home-run ball. Because the park's orientation allows views into the stadium, admission will be required during Padres games, but otherwise, it will remain open to the general community.

"Providing a quality experience and integration with the city, that's really the big amenity," says Pastier. "It's the harder one to achieve, but it is far more satisfying when it is."