Base closures and realignments offer a unique opportunity for municipalities and private developers to reuse, augment and create new recreation facilities

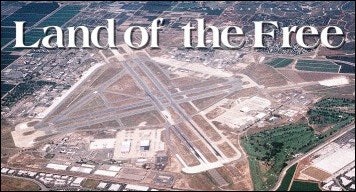

During its heyday in the 1960s and '70s, El Toro Marine Corps Air Station served as a primary gateway for military personnel and aircraft headed to Vietnam, and even accommodated Presidents Lyndon Johnson and Richard Nixon, both of whom frequently landed there to meet with Marine Corps generals. Back then, the lively military installation could hardly be considered an appropriate place for children to gather for a spontaneous game of hide-and-seek or for Little League practice.Yet within just three years, the land that until recently was home to this Southern California military base will be used for precisely those recreational activities, in addition to educational, residential and commercial uses.

As planned, the Orange County Great Park will encompass more than 3,700 acres and introduce to the region a 350-acre passive recreation area, a 150-acre sports park, 45 holes of golf, 3,500 housing units, a university campus and more than 3 million square feet of commercial/industrial office space.

Land developers can thank the Base Realignment and Closure Act, or BRAC, for making El Toro and most of its 4,700 acres - located in the center of Orange County - some of the hottest real estate in Southern California. Although it didn't close until 1999, El Toro was a 1993 casualty of BRAC, the process by which the military, under the direction of the Department of Defense, streamlines the number of facilities it operates at home and abroad. Since 1988, more than 350 major and minor bases and installations have closed and 145 others have had their missions realigned. Closed facilities and the land they occupy are then distributed. The BRAC pecking order dictates that other defense needs are addressed first, and then the remaining federal agencies get their crack at the properties before they are offered to local government entities. (For example, the Federal Aviation Administration and the Federal Bureau of Investigation together claimed nearly 1,000 acres of El Toro's land.)

In theory, BRAC offers exceptional opportunities for all parties involved. The military reduces its maintenance overhead, while municipalities potentially have at their disposal land that for years was off-limits. Of course, there are many steps - and genuine concerns, including economic, environmental and political issues - that must be addressed between the moment a base is relegated for closure and the day its redevelopment is complete.

In Orange County's case, there were significant divisions among area politicians and residents regarding El Toro's future use. Initially, business leaders and county officials promised the creation of new jobs and economic growth if El Toro were redeveloped as a regional commercial airport that could help alleviate the load carried by Los Angeles International Airport. In 1994 and 1996, Orange County voters passed two referendums supporting an aviation reuse.

Meanwhile, another group of county residents, primarily from the cities of Irvine and Lake Forest, argued against such a plan and instead envisioned the development of a large urban park. Park proponents pointed out that the Department of the Navy, which operates Marine Corps installations, decided to pull the plug on El Toro because it felt the base could no longer accommodate substantial air traffic (urban encroachment on the base's west, east and south borders, combined with its close proximity to a mountain range to the north, had significantly altered flight paths). Two more initiatives, the latter passing last March, reversed the county's earlier course of action and mapped out for the future of El Toro a giant park. "You were either in one camp or the other," says Daniel Jung, director of strategic programs for the City of Irvine. "It was a challenge and unfortunately, it turned into a civil war. Literally, it was South County vs. North County."

It's neither uncommon nor surprising that base closures initiate such feuds. After all, closing the doors to a major military base could mean an economic loss in the hundreds of millions of dollars, a crushing blow to any region. In June, when the Department of Defense announced that 2005 would bring its next round of closures - this one affecting an estimated 20 to 25 percent of all military installations - politicians across the country rallied passionately around their local bases. "The gut reaction is, 'We don't want this place to close.' Very few say, 'Yes, close me,' " says David MacKinnon, associate director of the Department of Defense's Office of Economic Adjustment (OEA). "There is a lot of what we call BRAC-proofing going on. States are developing 'war chests' for communities to do studies showing why their location is the very best for this or that and why they should never be closed or realigned."

MacKinnon's office does its very best to make sure that when a base closes, there is little (if any) permanent economic injury. By working with a local redevelopment authority - a quasi-state entity created to represent a community's diverse interests and facilitate the land transfer and redevelopment - the OEA helps communities plan for life after defense, providing technical and financial assistance in the development of feasibility studies and base reuse plans.

The OEA also helps determine the most appropriate means by which to parcel out former base property. A shuttered base that suddenly frees up 2,000 acres would be a boon for any parks and recreation department, but exclusive use as a recreation amenity might not be sustainable by the local economy. "A base closure's going to mean job losses and military people going elsewhere," says MacKinnon. "It sometimes affects the local housing market. There are all kinds of programs that help civilians find other jobs. The focus is usually on creating at least the number of jobs that were lost in the shortest period of time possible. Some communities are in a better position to deal with that than others. You really have to look at market demand, and that tells you that in some cases there's a market for only a small portion of the base to be used for job creation. In other places, it's almost the whole thing."

Because there is no generic formula, the BRAC process allows for the disposal of former military property through several means: public benefit conveyance (PBC), economic development conveyance (EDC), negotiated sales and public sales. The OEA's ultimate goal is to diversify the local economy and expand its tax base. To ensure those things take place, a base will often be parceled out using a combination of these methods. Land transferred through PBC is designated for recreational, educational, correctional, transportation or healthcare reuse, and best of all, it is given to the local government at no cost. PBC property is to be used perpetually for its given purpose, except in the case of educational reuses, which are bound by a 30-year covenant. EDC land can also be transferred at no cost, and is used to spur local economic development and job creation, whether that's through the construction of industrial parks or low-cost housing, for example.

Negotiated sales are just that, and also offer communities a prime opportunity to net a good deal. Public sales, however, often wrest away from local governmental entities much of the control they would have through the other conveyances. "Most communities feel that they've got to control this process and if there's a public sale of a portion or all of the property, they've lost control of the process," says MacKinnon.

Although public sales are a last resort, it seems as if at least one branch of the military, the Navy, is beginning to look favorably upon this method. Late this fall, El Toro's 3,700 acres will be auctioned online in four parcels ranging in size from 200 to 1,700 acres. And if last year's online auction of 235 acres at Tustin Marine Corps Air Station, also located in Orange County, is any indication, the Navy will make a killing off El Toro. Most of Tustin's 1,600 acres were transferred to local governments through PBCs and EDCs, but the three parcels that were sold netted the Navy just over $200 million. (The land is currently being developed for townhouses, apartments and duplexes.)

Certainly such income could help offset the military's astounding cost of cleaning up its former installations, for which it is entirely responsible. (MacKinnon estimates a $15 billion price tag for cleanup during the previous four BRAC rounds.) Ridding military base property of environmental contamination is a painstaking process that requires extensive testing. Often, such investigations and the prescribed cleanup that follows can drag on for several years. Then again, some sites may be found to be virtually free of harmful contaminants. (For example, equipment storage bunkers present a much less messy task than underground fuel storage tanks, which can rust through after extended exposure to groundwater.) Each site - and individual areas of that property, as well - will present various environmental challenges. Says MacKinnon, "If you've got a lot of unexploded ordnance, you don't want public use of that property. Wildlife conservation is probably the best use. The deer aren't going to be digging in the ground."

By the time a military property is clean and found fit for transfer, decisions regarding its reuse must be made. Of course, that can be easier said than done. In a situation not unlike what happened after El Toro closed, government officials with Horry County, S.C., and the City of Myrtle Beach found themselves embroiled in controversy after their local military stalwart, Myrtle Beach Air Force Base, closed in 1993. The county, which owned and operated the area's only commercial airport (some facilities were shared with the Air Force), hoped to expand once the base closed. Yet the airport's land sat entirely within Myrtle Beach city limits, and Myrtle Beach officials envisioned for the property a master-planned residential development.

The intergovernmental squabbling continued throughout the '90s, even after the state legislature stepped in and created the Myrtle Beach Air Force Base Redevelopment Authority (MBAFBRA) in 1994. "This is no different than in any other community that has been through a closure," says Buddy Styers, a retired Air Force base commander and executive director of the local redevelopment authority. "Every one of them has had well-meaning entities. They just have different visions."

Representatives of the state Legislature, the governor's office, Horry County and the City of Myrtle Beach all sit on the authority's board of directors, but it wasn't until 1999 that these individual interests saw eye to eye on a unified reuse plan for the former base. Once they did, no one's been able to hold the bulldozers back.

Slated for completion in just three years, South Park Village - a 101-acre "traditional neighborhood development" featuring a mix of residential, retail, commercial and recreation uses - is at the crux of Myrtle Beach AFB's second coming. The base's 3,900 acres have been doled out in such a manner that, according to Styers, everybody is happy. The county received more than 2,000 acres to enable its airport to receive international flights (although Styers says it'll be years before the existing facility reaches a capacity necessitating a second runway), 1,500 acres were given to the state forestry department, and a regional technical college got 75 acres to build a new campus. The City of Myrtle Beach - in perhaps the best deal of all - secured 12 acres for a fire department training academy, the former base's 240-acre golf course and 170 acres of parks and recreation facilities, the latter of which are being entirely developed and financed by South Park Village sales (as of July, more than $15 million in public infrastructure projects had been completed). Some of those parks help line South Park Village's system of small lakes that link the Atlantic Ocean to the Intercoastal Waterway, which runs parallel to the coastline several miles inland.

The amount of work being done is at times staggering, so much so that Styers can't help but point out the positive economic impact to the Myrtle Beach community. "By the summer of 2001, we had created more than 1,000 jobs on the base property. The base only lost 800 civilian jobs," he says. "In 1997, the base paid zero real property taxes to our community. Last year it paid $1.5 million."

Officials with the Myrtle Beach Cultural and Leisure Services Department are pleased with the arrangement, as well. "We got all this for nothing. The only thing we have is operating costs and then we put some money into the rec facilities. It was a drop in the bucket compared to what it would have cost if we'd had to purchase all those things," says cultural and leisure services director Jimmie Walters. "There was a lot of fear in the community that if the base closed, Myrtle Beach would suffer economically. But in retrospect, it really jump-started everything around here. As soon as the base closed, landowners started developing a lot of property for tourism and retail outlets. We really haven't seen a blip on the radar screen from this at all."

El Toro stands to offer similar opportunities for both Irvine and Orange County - that is, once the former base has been entirely freed from the stranglehold of political controversy. As recently as June, Los Angeles city officials secretly petitioned the U.S. Department of Transportation to reconsider an aviation use for El Toro, which would effectively override the Navy's decision. Although the Department of Transportation refused, some close to the project are fearful that in the coming months, other Great Park opponents will emerge and attempt to hinder the process.

The former base property is already zoned for its future uses, but Irvine must finalize the land's annexation from Orange County before the online auction can take place. Jung is confident that everything will carry on as planned, calling this step a simple formality since the city and county governments are at long last in agreement on the base's future. "I've worked on the project for 10 years and I always felt that we would succeed," he says. "It has been a long, drawn-out battle, but I never gave up hope."

"It's not always easy," adds Myrtle Beach's Styers. "Government officials do what they think is in the best interest of the community, and these things take time. But I am very confident that someday, there's going to be a beautiful community built on the former base that is going to make everybody very happy."