Policy experts from IHRSA and NRPA square off in a no-holds-barred debate on the fair-competition issue

All politics is local. It's an old political truism that - in the world of municipal recreation, anyway - is increasingly untrue.

In community after community, health club owners are challenging public recreation center projects on the grounds that these new centers threaten their clubs' very existence. While local issues inform each ensuing debate, the clubs' arguments bear, of late, a national stamp - that of the International Health, Racquet & Sportsclub Association. IHRSA offers clubs advice, partially funds some of their anti-rec center campaigns, and lobbies heavily in state legislatures in favor of bills that would limit competition - or, if you will, "unfair competition" - emanating from public-sector or nonprofit agencies.

IHRSA expended most of its efforts over the past decade on the latter type (mostly YMCAs), which may explain why the National Recreation and Park Association was a little late in getting to the party. But as IHRSA's bombs have begun falling on public recreation center projects, NRPA is arming itself, as well, hoping to create a unified approach to defending local rec departments while matching IHRSA's national lobbying efforts.

Athletic Business waded back into this morass in September, convening the forum that follows with the two organizations' directors of public policy: Helen Durkin of IHRSA and Barry Tindall of NRPA. While the resulting feature has been constructed to approximate a one-on-one debate, at no time did the participants speak directly to each other. While you might assume that we did this for safety reasons, both Durkin and Tindall stressed that meetings between the two organizations - several have been held over the past few years in an attempt to find peaceful solutions - have been extremely cordial.

More surprising, though, is the two public policy directors' own political leanings. Durkin, extremely fluent with her organization's anti big-government stance, is a self-described Democrat. Tindall, though a strong advocate for his organization's public-welfare agenda, is a self-described conservative. All of which might serve to remind us that, at its essence, all politics is, well, politics.

AB: The position of private health club owners is probably the simplest to sum up.

IHRSA: Part of the reason this subject is so complicated, strange as it might sound, is that in some ways the arguments on both sides are so simplistic. But the deeper you dig, the more elusive black and white becomes. It's a continuum with really bad examples of unfair competition on one side, and on the other side public facilities that no one would think are bad examples.

Our opinion, though, is that government shouldn't duplicate services being offered by the private sector. Are there places where government should spend the dollars to build facilities? Yes. I think our job is to raise the question of whether a particular instance is appropriate.

NRPA: We find it disturbing that certain organizations would perpetuate the notion that they should be the ones who make the distinctions about what constitutes "unfair competition" - that, you know, Community X or Y shouldn't have a recreation center with fitness equipment.

IHRSA: We don't make that call for local communities. Do we pick out public recreation centers to target? We never do. We don't sit there saying, "Who should we go after next?"

We give local clubs a bit of seed money, and it's not a lot of money. Especially on a park and rec grant, on a local battle the most we are authorized to give is $2,500, and that only represents half of direct costs. It's not paying for stamps or staff or anything. Part of the reason we only fund half of direct costs is that all the efforts we fund are locally driven. If it's a big enough issue on the local level and it's critical to one of our members, then we support them because we believe philosophically that's an important thing to do.

NRPA: I don't think IHRSA can duck their involvement in these local battles; their fingerprints are all over this stuff. Whatever the dollar amount is, they have this war chest. They give prominence to the objective of knocking off public park and recreation projects in their magazine. This is a regular drumbeat, and Club Business International's latest article is only the most blatant. I'm reading from the September issue about club owner Joe Moore - it identifies him as "Executioner" - and it's subtitled, "Joe knows that tax-exempts can be beaten and is showing others how."

But beyond just the language, we fail to understand why they continue to lump public park and recreation entities in the same bag as nonprofits. They're radically different by statute, operations and purpose.

AB: How are they different?.

NRPA: Public parks and recreation services go back to the late 1800s, early 1900s. They come out of state health and welfare clauses, and that's exactly what their purpose is: Health and welfare through recreation activities, both physical and mental. In some of the older Eastern and Great Lakes cities, the public recreation agencies were carved out of the welfare agencies, because city fathers and social advocates realized the distinct differences between a social safety net in general and the functions that municipalities and cities should be performing in the form of recreation.

AB: And yet, public recreation departments do hold an advantage over for-profit health clubs in the same markets.

NRPA: Local park and recreation agencies are not tax-exempt. Now, they're not required to turn a profit, and their facilities are built using tax revenues rather than private capital. But they're public agencies, organized to promote and engage in things that are an element of the health and welfare of the community collectively - as opposed to a businessperson who chooses to invest in a club facility and the user of that facility who chooses to take his or her discretionary money and buy a membership. They arise from different purposes. One is entrepreneurial spirit, and the other has a public purpose. Parks and recreation is the same animal as a public school system, or the fire department - they're in the public welfare business.

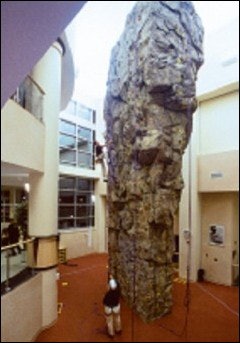

IHRSA: I don't think you can ignore the changes in the industry over the years. I did the Colorado Recreation Facilities Design & Management School five or six years ago, and those places are phenomenal! In Boulder, I could climb on a rock-climbing wall that looks out on the Flatirons, and then I could swim in their theme-park waterpark. Those kinds of facilities aren't the same as the park and recreation agencies that started the whole thing. Is there a place for public recreation? Absolutely. The question that the public should ask in their communities is, How far should they go? Does my community need a government-subsidized climbing wall and water park?

AB: So this is really just a question of degree?

IHRSA: Well, it feels like from our side that park and recs have such a brick-and-mortar focus now. And you could take that money - man, that money could go pretty far in terms of using existing resources in the community. The way people spin this is to say, "Oh, if you're against a park and rec you're against athletics or a healthy community." I think there are more ways to achieve a healthy community than simply saying you have to have a $25 million facility.

NRPA: Recreation centers and recreation programs are almost a hand-in-glove situation. When you build a center, develop a park, put in a trail system, you do it because you have social services that require a structure.

AB: Then why build a $25 million recreation center when you can build a $10 million recreation center?

NRPA: Maybe there are more $25 million recreation centers than I'm hearing about.

AB: Rec centers are getting bigger and glitzier.

IHRSA: Right. Look at Chicago - they're not building these new glitzy centers downtown, they're putting them in suburbs so wealthy that even I, who am used to Boston housing prices, couldn't afford to live there.

And you know, up until a few years ago, no one was organized in a way to present the arguments against these projects. They got a free ride. Now there are arguments being presented against them. There is someone with expertise saying, "Wow, the square footage they're looking at is inordinately expensive." Or, "Where's the year-to-year financial support?"

For some of these park and recs, local club owners are saying the emperor has no clothes. On the other hand, there are wonderful facilities in communities that need them. We can't and never will make any blanket statements saying, "These kinds of facilities are good, and these are bad."

AB: You did suggest that it was inappropriate for governments to be in this business.

IHRSA: We believe - and this is a basic tenet of the political philosophy underlying the current administration and the Republican party in general - that if a service can be provided privately, then the government doesn't need to do so. The question is, is it appropriate in a given community? And that's open to the debate and the decision of the community. It's only fair that it be debated by the community and not be a one-sided presentation.

I know it's annoying if you're a park and rec director, but this is the first time anyone's told what the negatives are going in. There can be negatives if they're spending $25 million to build a rec center and it's an area where towns are closing schools.

NRPA: I was on the staff of the President's Commission on Americans Outdoors in 1985-86, and we had 18 hearings around the country, and out of dozens of issues there were two things that people kept talking about. They wanted recreation access close to home, and we kept hearing the word quality, quality, quality. People want public rec centers that are fully functional, are safe and secure, and are well-managed. The American people demand that from their public agencies, whether they're talking about a fire station, a city hall or a public recreation center. And often there's a demand that the city accommodate good public architecture, public art and so forth - and even that the private sector should emulate it.

IHRSA: There are degrees of anything for the government. Is it OK for the government to run food banks and soup kitchens? Absolutely. Is it OK for the government to be running five-star restaurants? This is not just splitting hairs. There is a difference between a food bank and a five-star restaurant.

AB: What if profits generated by the five-star restaurant were funding all the soup kitchens?

IHRSA: On the nonprofit side, that's the argument you hear all the time. But the reality is that's not how our tax law works. It goes back to the NYU case back in the 1950s, where the university owned one of the big spaghetti companies and said they could do that because they were taking the profits and putting it toward scholarships. The courts said the source of the income has to be for an exempt purpose, not the destination.

NRPA: I don't know that case, and I'm not an attorney. But let's talk about tax issues. IHRSA can't have it both ways. They can't be knocking local public investment of tax money on the one hand, and looking for federal tax relief on the other. They are lobbying heavily for a federal bill, HR 1818, that would allow a corporation to deduct from its gross profits, and thus from its tax returns, the membership fees it paid for its employees to belong to private clubs. They exempt golf clubs and equestrian clubs, and maybe one or two others, but that's a direct federal handout that you're paying for and I'm paying for.

IHRSA: The Workforce Health Incentive Provision allows health-club memberships to be treated as a nondeductible fringe benefit. We don't see any inconsistency here.

AB: Would businesses pay less taxes under WHIP or not?

IHRSA: I have no way of knowing what the impact would be. I've heard club operators argue it both ways.

AB: That's far from IHRSA's only foray into the legislative arena.

IHRSA: We track 500 pieces of legislation.

AB: Two of those are essentially identical bills currently winding their way through the Pennsylvania House and Senate that would bar governments from competing with private enterprise "unless it can be shown that private enterprise is unwilling or unable to engage in the proposed activity." Three years ago, IHRSA Executive Director John McCarthy wrote in CBI that public rec centers could be appropriate so long as clubs were given prior notification and the public was given accurate impact figures and so forth. The Pennsylvania bills, though, seem much less forgiving in their intent.

IHRSA: We believe that government at all levels should avoid competing directly with taxpaying businesses, and that it is important to pass legislation that guarantees that the government take into account the small-business community. In most states this isn't necessary, because we don't see aggressive growth of park and recs that blur the line between government and business. However, in some states, we have seen governments that we feel are wasting public dollars because they are unwilling to take into account the services already being offered by the taxpaying sector. This ultimately hurts the community by either taking away from core services or by raising the tax burden higher than it need be.

These kinds of measures are sometimes necessary to ensure that the government makes responsible fiscal decisions.

NRPA: We gave testimony in May before the Pennsylvania House, and the vast majority of witnesses in favor of this were private club owners. It doesn't mention parks and recreation at all, but we think it's aimed at us. On the surface, it fails both the credibility test and the practicality test. State courts have found repeatedly that local and state governments can go head to head with the private sector, whether clubs or grocery stores, as long as the outcome serves a public purpose.

AB: Is IHRSA, as some people accuse, trying to legislate public rec centers out of existence?

IHRSA: If they're operating within the mandate of the public, because it's been approved by the public after full disclosure of the facts, or if it's paying its appropriate share of taxes, then our argument stops there. We don't say, "We want to wipe you off the face of the earth." Our argument is, If you're going to play, play fairly. I rarely get a call about a JCC. Why? Because they are marketing to the Jewish community, and their programming is so infused with the whole religion and culture, that clubs feel that's fair. Clubs are not going after everyone.

AB: Still, the CBI piece on Joe Moore had a certain indiscriminate quality - in the opening paragraph, he boasts that "we can defeat city hall - 100 percent of the time."

NRPA: Every one of those proposed facilities that Mr. Moore suggests that he was responsible for defeating, they might have been the worst proposals in the world. I don't know - and he doesn't know, either. He's using his perception, aided and abetted and encouraged by IHRSA, to determine what's needed and not needed. He doesn't talk about services and needs, he's talking about his business ventures.

But the worst thing is, knocking off rec centers has other consequences. It would be interesting to put a footnote after every one of those projects that he defeated or caused not to happen that says, "Thus, x number of people are not served, or are underserved, or have been deprived of a public recreation experience or facility." If they want to continue this campaign of boasting about initiatives that they've derailed, somebody ought to complete the picture.

AB: Do you think Joe Moore's victories are good for the industry as a whole?

IHRSA: I do. You know, there are decisions being made all the time, by the tax-exempt and government side, to put facilities in places that no for-profit would, ever. I just took a call from a guy who runs a women-only club, and the YMCA just put in a women-only annex right across the street. A lot of what Joe Moore and others are dealing with are facilities that aren't in locations that really make sense from a business standpoint. I'll tell you this, if a for-profit business was siting a new facility, they wouldn't put it two blocks away from a competitor.

NRPA: Well, it's not a perfect world. I'm sure you could find a public recreation center that sits across the street from a club. But location in and of itself does not equal unfair competition. The demographics of club membership and the usage of public park and recreation facilities are often very, very different.

IHRSA: Everyone says we're serving different groups, but this is clearly an industry that could use more data. To my knowledge, there's never been any data that has shown that there's a significant difference in the demographics.

NRPA: My guess is that most private clubs cater to people of some means, or at least sufficient means for them to choose to use their discretionary income to pay an initiation and membership fee.

But also, the role and function of park and recreation agencies is far broader than building a recreation center. Almost every public recreation agency has some sort of scholarship program. Parks and recs are in touch all the time with other social welfare agencies, such as juvenile justice, to find out what needs there are in the community. Public rec centers, old ones and new ones, are serving meals and snacks to hungry kids when school's not in session. That's why to isolate rec centers - and not just rec centers, but rec center A, D and Z among 35 rec centers in a city - is just cherry-picking.

IHRSA: That argument is really convenient; they say, "It's not OK to look at us in bits and pieces, you have to look at the whole package." We're not willing to take the whole package. These functions all need to be justified. When you go to the Salvation Army to buy secondhand clothes, other stores don't complain about that. If the Salvation Army started selling Armani suits, would NRPA argue that "Oh, but they're selling secondhand clothes, too"? The idea that a rec center that goes three steps too far is OK because it's related to physical fitness is an argument we don't buy.

AB: It appears an increasing number of people don't buy it, either, judging from the many lopsided losses park and recreation departments have suffered at the ballot box.

IHRSA: Part of the reason is that people are realizing there won't be a majority of people in the community who'll use the recreation center. The other thing that we see time and time again is the need or want for a recreation center coming up through the park and rec department. It becomes an idea that's been internally generated.

AB: Aren't recreation departments responding to demand in some way?

IHRSA: I went to one of the seminars at the AB Conference a few years ago, on performing surveys for a rec center, and I sat there and listened while they talked about how you could ask questions in such a way that you could get a higher percentage of "yes" responses.

NRPA: Let's take it out of parks and recreation: If you are an advocate for good schools, aren't you going to create the strongest message that you can to get the bond issue passed? I'm surprised that's even an issue.

IHRSA: But there's a whole industry that's grown up that has a financial stake in having more facilities built. And some of those people are the same people doing the feasibility studies. Sometimes, the data gets skewed.

The other thing is, if it's presented in a way that doesn't seem to cost you any money, the answer is, "Sure, why not?" But the question should be, "Do you want a rec center more than you want more teachers in your school?" There are only so many government dollars.

NRPA: I think we should remember here that something on the order of 80 to 85 percent of bond issues or millage rate increases succeed, notwithstanding the boasts of people like Moore.

We've done a number of surveys of capital investment needs in park and recreation systems, and these are plans that for the most part are based on tremendous amounts of public participation. The really telling statistic is that while people brag about knocking off bond issues or related revenue-development initiatives, between 45 and 50 percent of local park and recreation capital investment is supported by general tax revenues. If citizens weren't supporting these things broadly, then there would be much more of a public outcry about the use of their general revenue.

AB: Are people well-informed enough to know how their money is being spent?

NRPA: In the area of parks and recreation, sure. But, really, who knows why some referenda succeed and some fail? Referenda and bond issues - on recreation centers, schools, roads, energy, almost anything that has some public dimension to it - rise and fall. Loudon County, Va., had a major school bond issue on the ballot about three years ago and a major park and recreation issue as well. The school issue passed and the park issue failed by about a point, simply because they had two very large bond issues on the same ballot. The next time the park bond passed overwhelmingly.

AB: It strikes some people as inconsistent that IHRSA claims, on the one hand, that business is booming, and on the other that its members are being pushed out of business by what it insists is "unfair" competition.

IHRSA: If all we had was the "Poor us" argument, we wouldn't win. Aside from the club owners and their staffs, no one cares about unfair competition. When people make a decision about where they're going to work out, they don't think, "Is it a park and rec, a hospital wellness center or a for-profit club?" They think, "Is it close to my house? Is it near my work? Is it a price I can afford? Is it a place where I feel comfortable and safe?" That's all that matters to people.

There are some people who shop locally and won't go to Wal-Mart because they don't feel it's appropriate, but you know what? Wal-Mart is doing pretty darn well. The public doesn't care. People make decisions with their pocketbook.

AB: To extend your metaphor, the new $12 million public recreation center is Wal-Mart?

IHRSA: Yeah. I'd liken it to local drug stores competing against the chains.

AB: It is true that when you build an upscale public recreation center, you attract upscale patrons?

NRPA: I can't deny that for a second. You might see a well-off businessperson working out. But maybe that well-off businessperson has his or her child somewhere else in the building.

But we just don't agree with the whole "unfair competition" argument. Where's the evidence that a public rec center has put a health club two miles away out of business? According to the Small Business Administration, there were 550,100 new small businesses in 2002, and 584,000 closures. Some of the closures - and I hope it's a very small number of them - are mom-and-pop health clubs. These companies come and go. What are some of the reasons? I'm reading from the SBA literature: "Overestimates of public demand for their services. Poor choice of location relative to market. Undercapitalization. Lack of management skills. Condition of facility or site. Social environment. Local or other market or economic conditions. Tax policy. Employee qualifications." And on and on.

It's absolutely an oversimplification to say that competition with a public rec center is what causes a business to fail, even if the new rec center is across the street. The closing of small businesses is not a new phenomenon in this country. Private-sector investments that rely on disposable income are very much affected by the overall economy.

IHRSA did a study of its clubs' own ex-members, "Why They Quit," and you'd think that if public rec systems were having any negative impact on their membership, that would have been reflected there. But that did not show up, which I think is pretty telling.

AB: One of the things you hear frequently from the public recreation side is that public rec centers serve as feeder systems for clubs, not the other way around.

IHRSA: Our problem is with park and recs and Ys that have decided they're not happy with just being the feeder system. Their intention is to build a facility and a program that's better than other facilities so that nobody would ever want to leave.

NRPA: This may sound extreme, but if I were a private club owner, I'd be urging investments in public recreation all over the place. I would market myself as the next step, the next provider after the kid outgrows the rec center. Most public systems sort of position themselves like that. You'll find very few systems that offer advanced karate, or advanced swimming, or advanced gymnastics. Most get people interested and create the next generation of club users.

We just don't agree with them that a feeder system should be the beginning and end of a public recreation program. Believe me, public rec centers want users to make a lifetime commitment, but the 15-year-old who's in a rec league isn't typically still in the rec league when he or she is 47. We're creating soccer fans, judo fans, jogging fans. We're introducing kids to a lifestyle that includes active recreation in various forms.

IHRSA: A Chicago public rec center I visited had 22 personal trainers on staff. I think that's a lot of personal trainers for a public rec center; do they really need that many? Who's that feeding? Why would a member ever leave that place?

AB: They would say their mission is to serve everybody, regardless of economic status.

IHRSA: When I toured some of those Colorado rec centers, I stood in one of those offices in front of a bulletin board that was telling the staff to go tour various private clubs, I presume to figure out what services they were offering so they could adopt them. That's what drives club owners crazy. If they're really thinking of themselves as feeder systems, then why are they adopting every brand-new, cutting-edge program that people want?

So, you know, I couldn't agree more with Barry. I think clubs would absolutely agree that if park and recs followed the mission that Barry stated, that would be fine.