A rash of ugly hazing incidents is leading school and athletic administrators to adopt more-stringent preventive measures

The Bellmore-Merrick (N.Y.) School Board sent a strong message to the Mepham High School football team, students and fans this fall when it canceled the Pirates' season three days before the scheduled opener. The board's bold move came in the wake of allegations that three varsity players sodomized three junior-varsity players at a preseason training camp in Pennsylvania, reportedly using a broomstick, pinecones and golf balls while other players watched. One of the victims was injured so badly that he reportedly required surgery.

Fueling the controversy were former Mepham players publicly recalling their own hazing episodes, including one who said older players dunked his head in a toilet at the beginning of the 1995 season and later beat him with cleats and helmets. Another former player told reporters that those kind of "swirlies" were "just the usual thing." Kevin McElroy, Mepham's football coach for 17 years, publicly apologized for the most recent incident, claiming he was not aware of the hazing - coaches reportedly slept in a different cabin than the players at the Pennsylvania camp - and that he also did not know of any previous hazing incidents. In November, McElroy was fired.

All players and parents signed a letter prior to the team leaving for the camp, specifically stipulating that players not participate in hazing activities, according to Saul Lerner, athletic director for the district. "The expectations are everywhere - and in print. The message is out there," Lerner told New York's Newsday. "Is that enough to stop a crime?"

Apparently not, as McElroy, four other coaches who accompanied the team to the camp and the three accused players were called to testify before a Wayne County, Pa., grand jury this fall. The players were also suspended from school but will be tried as juveniles on charges ranging from aggravated and simple assault to involuntary deviate sexual intercourse.

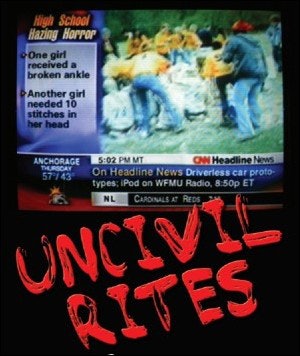

In the wake of Mepham's incident - and perhaps because of it - numerous other hazing reports made headlines in newspapers around the country during the first two months of the 2003 high school fall sports season.

As these stories demonstrate, the victims aren't the only ones who suffer in a hazing episode. The Bellmore-Merrick School Board has paid a high price for canceling the football season, not only financially but also publicly, in the form of irate parents, student protests and potential lawsuits.

"Anytime a hazing incident - especially one involving sexual misconduct - occurs at a school, it's the biggest problem that school will ever have," says Hank Nuwer, a professor at Indiana University and Franklin College, and author of several books about hazing. He adds that nearly 50 hazing incidents involving sexual misconduct have come to light since 1983 - most of them after 1995.

In October, Athletic Business surveyed high school athletic directors to find out how they're addressing hazing, if at all. One in five of 58 respondents reported that their school had experienced what they consider a hazing incident during their tenure there. (Defining hazing can be dicey, but according to Nuwer's 2000 book, High School Hazing: When Rites Become Wrongs, hazing "involves activity that requires new members to show subservience to older members of the group, lowering the self-esteem of newcomers." Another common rule of thumb: "If you have to ask if it's hazing, it is.")

Nearly one in three respondents indicated that either they do not have a specific hazing-prevention policy in place or their school's code of conduct does not address hazing in any way. Several respondents are in the process of updating their policies, and one - who encountered hazing this fall but isn't offering details - is creating a policy.

"No matter what you do, you're never going to stop everything that's possible from occurring. Hazing does happen, and it could happen anywhere," says John Morgan, athletic director for Bexley (Ohio) City Schools, which implemented a new anti-hazing policy June 1 for its three elementary schools, one middle school and one high school. "We just have to create an environment that makes it less likely to occur. If kids are out there, getting hurt and intimidated, we can't just brush it off. We have an obligation to make a safe learning environment for them."

"I have been in education long enough to know that we've probably had some incidents," says Don Patrick, athletic director at Newton-Conover (N.C.) High School, who admits his school should have a written hazing-prevention policy in place but doesn't. "We have always asked our coaches to take a strong no-tolerance rule toward hazing. We let student-athletes know that they face the possibility of being eliminated from any team if found guilty of any form of hazing, we try to teach a 'togetherness' approach and let student-athletes and parents know that hazing violates that expectation, and we hope tomorrow is as good as yesterday."

There's no question in Nuwer's mind that administrators in schools across the country need to implement some sort of hazing-prevention program to make students aware of the consequences that come with violating it. An effective policy accomplishes four major objectives, he says. It protects a school legally, it makes students aware that their actions will not go unpunished, it demonstrates to other students and the community at large that hazing will not be tolerated and it invites input from victims and concerned observers.

Says Morgan, "Having a policy is like having insurance: You need it, but you hope you never have to use it."

With a history that dates back to ancient Greece, hazing as a rite of initiation takes many forms, from playful foolishness (requiring newbies to carry older players' equipment, for example) to dangerous and sometimes fatal practices (forcing excessive alcohol consumption). Once the domain of college fraternities and sororities, hazing has now become common - some experts may argue even more common - in college and high school athletics.

That trickle-down effect is illustrated by a series of major incidents that came to light at all three levels this year. Walter Dean Jennings, an 18-year-old freshman at the State University of New York Plattsburgh and a pledge to Psi Epsilon Chi, an underground fraternity without campus recognition, fell unconscious and died in March after a 10-day hazing ritual known as "water torture," during which he drank so much water (sometimes via a funnel) that his brain swelled.

Around the same time the Mepham story was breaking, news came from the University of Maryland that 44 members of the men's and women's lacrosse teams were suspended for all or part of the fall season because of hazing allegations involving underage drinking.

But the story that really caught the nation's attention - and that of Oprah Winfrey, who aired a video of the incident in its entirety on her show - happened last May during an off-campus powder-puff football game at Glenbrook North High School in the Chicago suburb of Northbrook, Ill. Caught on tape were senior girls beating junior classmates and smearing mud, paint, garbage and feces on them. Five victims were hospitalized, 16 students were charged with misdemeanor battery and 33 seniors were expelled after the incident - which generated hundreds of e-mails and phone calls to Glenbrook North administrators during the final weeks of the academic year, lambasting the school, its students and staff. (The incident was not an isolated one: In September, as many as 60 upperclassmen boys and girls from Huron High School in South Dakota allegedly dumped vomit, urine and cow manure on 20 freshman girls at an off-campus site as part of an unsanctioned homecoming "tradition.")

Since last spring, officials from Glenbrook North and its school district developed a task force to examine the factors that contribute to hazing, such as underage drinking, bullying and parental involvement. (At least two parents were charged with providing alcohol to students prior to the powder-puff football game.) The task force includes officials from other schools, teachers, parents, students, state representatives, community leaders and police officers.

The Glenbrook North debacle was the last straw for Bill Stanley, a business teacher and head boys' tennis coach at West Aurora High School, located about 45 miles southwest of Northbrook. When he realized his school did not have a written policy against hazing, he created his own task force of sorts. As a class project, Stanley encouraged the 29 students in his spring semester Business Law II class to search the Internet for anti-hazing policies at other high schools and school districts around the country, compile them, solicit input from classmates and other teachers, and develop a district-wide policy for all students. The school board welcomed the input, made a few alterations to the policy, and put it into effect this summer.

Stanley also has a personal stake in the policy. In 1990, his friend Nicholas Haben, a freshman at Western Illinois University, died from alcohol poisoning after a lacrosse club drinking ritual. In fact, Haben's mother, Alice, who speaks to groups about the hazards of hazing, was instrumental in providing information and insight to Stanley's class. (See "Rite Answers," May 2000, p. 32.)

West Aurora has never experienced a serious hazing incident, Stanley says, and he wants to make sure it never does by heightening hazing awareness. "I figured if the kids created it, the kids would follow it," he says of the policy, adding that teachers and coaches emphasized the policy to students at the beginning of the school year and each sports season.

Following that credo, Bexley, Ohio, officials last spring developed a community-wide committee to update that district's previously vague policy. In addition to including administrators, coaches, the mayor and the police chief as members, about 20 or so students invited by Bexley High School's student council participated in updating the policy.

"The only way that kids' behavior is going to change is to empower kids," says Morgan, head of the committee. "Hazing is related to athletics, but it's not an athletics-only issue. However, if you can get the message to the athletes, you go a long way toward changing the behavior of a lot of other students, as well. The main thing the committee did was take hazing and make it something that was OK to talk about. People knew we were working on this. That, in and of itself, was probably a deterrent to hazing behavior."

Bexley's policy - which requires students, faculty, administrators and other employees to report possible hazing incidents and was explained to individual high school classes during sessions with the school principal - does not spell out the consequences for specific actions, because each case is different. Instead, it simply states that disciplinary action, including civil and criminal penalties, is possible.

Neither West Aurora nor Bexley officials waited for an ugly incident to occur to jump-start their new hazing policies. But last January, Central Catholic High School in Pittsburgh adopted one after a 2002 football practice during which a sophomore and junior restrained another boy and reportedly touched his face with their genitals. After teammates refused to talk to school officials about what happened, administrators withdrew the team from the Western Pennsylvania Interscholastic Athletic League football playoffs. The new policy requires athlete supervision at all times and is in place at all schools within the Pittsburgh Catholic Diocese. Athletic directors are responsible for enforcing the policy.

To at least one parent, that policy is not enough. The victim's father told the Pittsburgh Post-Gazette that the policy was a case of "too little, too late as far as I'm concerned," while the boy's lawyer called the policy "damage control" and said one should have been in place long before his client became a victim.

That said, the mere existence of a policy doesn't guarantee compliance. At SUNY Plattsburgh, such anti-hazing measures as a hotline for anonymous tips, education workshops, a bill of rights for fraternity and sorority members and a pamphlet distributed to all students titled "Hazing: A Trust Betrayed" were in place at the time of Jennings' death. Glenbrook North reportedly had an anti-hazing policy in place, too. So what went wrong?

"Having a policy is certainly not enough," says Elizabeth Allan, professor of higher education leadership at the University of Maine and co-founder of StopHazing.org, an Internet resource with the motto "Educating to eliminate hazing." "The issue of hazing is far too complex to just think that having something written on a piece of paper will be the answer."

A policy's effectiveness depends on the people placed in the position of enforcing the policy, she says, including their title and authority, their understanding of hazing and their morals regarding hazing. Indeed, some hazing incidents reportedly occur in the presence of coaches, who either turn a blind eye to the behavior or consider it a good-natured and traditional component of participating in team sports.

Many athletic directors hope they have found successful ways to mitigate hazing. For example, in addition to enforcing a district-wide zero-tolerance policy against hazing, Clovis (Calif.) West High School athletic director Karen Sowby also makes her student-athletes sign and abide by a co-curricular code of ethics. If anyone violates the code, that student-athlete and his or her parents must face an athletic board comprised of Sowby, the school's deputy principal, the learning director and the coach. A first-offense violation of the "Hazing/Intimidating/Harassment" section of the code results in a suspension from athletics ranging in length from two to 18 weeks, depending on the severity of the violation. A second offense can result in a 19- to 36-week suspension, while a third offense will likely force a student-athlete to sit out for one to two years.

"Coaches remind their athletes weekly about proper behavior," says Sowby, who also makes her coaches sign a code of conduct. "Many coaches end their Friday practice by reminding their athletes to 'Have a safe weekend,' 'Remember to do the right thing,' stuff like that. We tell our athletes to use the code as their excuse for just saying no. 'Sorry, I am an athlete and I can't do that. I want to stay on the team.' "

On the other side of the country, student-athletes from the Eastern Connecticut Conference participate in student leadership luncheons sponsored by a local Coca-Cola bottler and an area newspaper. Three times a year (once per season), two players from each school and each sport are invited to dine with their peers and discuss important issues like hazing and ways in which it can be prevented.

Additionally, Nuwer suggests athletic directors apply for grant money to help train administrators about hazing-related issues. They should also interview students involved in hazing to find out why they did it, and even rally judges to include as part of a convicted student's community-service agreement talking to groups at surrounding schools about the cold realities of hazing. "Kids aren't going to listen to someone my age, who's almost 58," Nuwer says. "They're going to look to their peers."

That's why some schools and districts now have mentoring programs in place that match older players with younger players, similar to the buddy system. "Usually, a freshman's first contact with the high school is athletics," Morgan says, referring to fall sports programs that start practice prior to classes beginning. Every upperclassman football player at Bexley this fall was assigned two freshmen to help ease the transition to high school. "If they can develop positive relationships with older students before they get into those halls, they'll feel more comfortable, and the older ones will be looking out for them," Morgan says.

Because many hazing incidents occur off school property, some of the latest hazing-prevention methods focus on camps and road trips. By implementing policies that make varsity and junior varsity players travel on different buses, stay in separate cabins and require coaches to sleep in the same rooms as or in close proximity to their players, schools are trying to convey the point that hazing will not be tolerated.

The National Federation of State High School Associations hopes to boost its involvement in hazing-prevention tactics next year by developing a handbook for all athletic directors that defines hazing, offers suggestions for coping with a hazing incident and provides resources to combat hazing. Developed with input from Nuwer, the handbook is expected to be available in time for the beginning of the 2004-05 school year.

"We've always had a position that hazing is unacceptable, but it's just getting worse and worse," says Elliot Hopkins, director of educational services for the federation. "This handbook is not going to be a cure-all. We just want to give those schools that have no policy a point of reference."

Other points of reference include laws against hazing that are on the books in no fewer than 43 states. But "a lot of them aren't worth the paper they're written on," Nuwer says, adding that some are too specific while others remain too vague. Some state laws aren't even invoked in hazing cases because prosecutors focus on the heftier charges, such as involuntary manslaughter, underage drinking or sexual assault.

Crucial to combating hazing is understanding why students haze in the first place. In an Alfred University study of more than 1,540 high school students published in 2000 - in which 48 percent of respondents admitted they'd been subjected to activity they consider hazing - students revealed that the top three reasons they haze is because it's "fun and exciting," to feel "closer as a group" and "to prove myself." Such responses as "I wanted revenge" and "I was scared to say 'no' " received fewer responses.

Yet consider what 16-year-old Josh Jackson told The Virginian-Pilot last spring in a story the paper published about hazing: "I believe hazing makes athletes strive to become stronger physically so one day, they can haze others." That mind-set can be one of the most damaging factors at play when trying to empower students to fight hazing among their peers, experts say.

Almost all of the Alfred University study respondents (98 percent) thought dangerous hazing was wrong, 86 percent considered humiliating hazing wrong and 43 percent assumed it was illegal. That said, 35 percent of the students still indicated that hazing was socially acceptable. (For more results from the study, go to www.alfred.edu/news/html/ hazing _study.html.)

That's not surprising, Nuwer says, considering that professional athletes engage in hazing on a regular basis. In a well-publicized 1998 incident, for example, three rookies were injured on the final night of the New Orleans Saints training camp at the University of Wisconsin-La Crosse while running a gauntlet of veterans and being struck with bags of coins. During NFL training camp this year, veteran members of the Minnesota Vikings, according to a lighthearted story in the Minneapolis Star Tribune, taped rookies to a goal post, pulled down their shorts and poured water and Gatorade on them. The Oakland Raiders of late have reportedly made a practice of physically overpowering rookies, restraining them and giving them unappealing haircuts, and Houston Texans rookies were bound with tape and doused with Gatorade during the preseason. Even LeBron James, the NBA's No. 1 draft choice, isn't immune, as his fellow Cleveland Cavaliers have made him carry their bags and buy them doughnuts.

Harmless or not, these incidents are sending the wrong message to high school student-athletes who emulate the pros, Nuwer claims. "There's been no leadership at all from professional sports teams," he says. "They've been totally derelict in this area."

Even more galling to Nuwer is the sexual nature of some hazing practices. This is an area he's currently researching, but his preliminary findings indicate that many male hazers engage in sexual misconduct as a means to prove their masculinity. "At that age, there is a great concern to not be considered insecure sexually. Students actually participate in this deviant conduct to show that they're not gay," Nuwer says, his voice expressing some of the frustration his research has wrought. "It's a distasteful topic. I mean, we're talking sodomy."

One day after Nuwer made his comments, the sordid details of another hazing involving sexual misconduct, this one in Friendship, N.Y., began to emerge. A 17-year-old soccer player for Friendship High School was charged with sexual abuse after a locker room incident during which the boy allegedly held a 14-year-old player to the floor, and exposed his genitals to the side of the younger boy's face. Following the Bellmore-Merrick School District's lead, Friendship administrators canceled the remainder of the soccer team's season.

Don't be surprised to hear about even more canceled seasons. If the news stories that broke nearly every week this fall are any indication, hazing appears to have reached a new level of acceptance among high school student-athletes. And judging by the radically different reactions by schools and communities affected by those incidents, there appear to be no easy answers.

But change eventually comes about. For proof, Nuwer points to the Greek organizations on college campuses. "What's happening in high schools parallels what happened with fraternities and sororities in the '70s, only then there was a rash of alcohol-related hazing deaths," Nuwer says, adding that many organizations - despite what happened at SUNY Plattsburgh - now have strong leadership programs in place that don't tolerate hazing. "Fraternities and sororities are better armed and better prepared than they've ever been. That will happen with high school athletic directors, too. I would bet it's going to take between eight and 10 years for it to happen - unfortunately, it will take one death or more sodomy cases to shorten that amount of time - but it will happen."