Major League Baseball's Cardinals and Dodgers shock fans with sportsmanship display

Soccer players trade jerseys after games. Hockey players skate at center ice for postgame handshakes. Basketball players shake hands at center court as they're announced prior to games, and football players are known to hold inter-team prayer circles on the field after. Tennis players meet at the net for their postmatch handshake, and tournament finalists appear together, the winner and loser holding up their respective trophies to sustained applause. Golfers shake hands and sometimes embrace on the 18th green. As for coaches, it makes the news if a football or a basketball coach refuses a postgame handshake. Among the professional sports in this country, baseball is alone in not having some form of ritual in which opposing players or coaches meet on the field - unless you count Pedro Martinez throwing Don Zimmer to the ground.

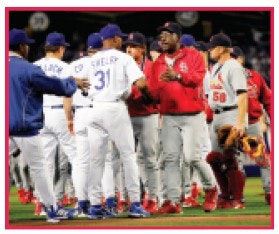

That all changed during the 2004 postseason, when the Los Angeles Dodgers left their home dugout after the St. Louis Cardinals closed out their best-of-five divisional playoff series three games to one on Oct. 10, and lined up on the field to shake hands with their adversaries. Television commentators, newspaper columnists, current players and old-timers, fans - and even sportsmanship advocates - were taken completely by surprise.

"Am I dreaming? I'm almost positive I saw handshaking on both sides," remarks Ted Breidenthal, a staff member with the Kansas City, Mo.-based Citizenship Through Sports Alliance. "I remember saying to myself that I'd never seen it, and thinking a couple of weeks later, after the Red Sox beat the Yankees in the American League Championship Series, 'Wouldn't it be a great scene if Jeter and A-Rod had come out and acknowledged the winning Red Sox players?' "

Rick Wolff, chairman of the Center for Sports Parenting and a semi-regular youth sports columnist for Sports Illustrated, had a similar reaction.

"I was wondering whether we'd see the Yankees come onto the field," he says a little ruefully, "but if they had, I'm sure Steinbrenner would have shot them."

The seemingly spontaneous display of sportsmanship was actually something that the Cardinals' Larry Walker, a Canadian and a big fan of hockey, had been thinking about since 1995, the last time he'd been in the playoffs (with the Colorado Rockies). In late September, Walker approached his manager, Tony La Russa, with the idea, regardless of who St. Louis played and the series outcome. After it became apparent that the Cardinals would play L.A., La Russa mentioned it to Dodgers manager Jim Tracy, a good friend, who gave the plan the thumbs-up. As La Russa waved to Tracy after the final out, he made a handshake motion, and Tracy led his team onto the field.

Walker told The Toronto Sun he respected hockey players who "beat each other up for a series and at the end shake hands," adding, "If it does take off in any way I hope it's done every series, that it's not a pick-and-choose type thing."

"Is this competitiveness so ingrained in baseball that handshakes are not a possibility anymore?" asks Breidenthal. "I don't know. I'd like to think that in this day and age civility and humility are still alive, and that athletes will win with civility and humility, and lose with dignity. I've always thought that the handshake in hockey is pretty darn cool."

John Halligan, the National Hockey League's director of special projects and its historian, says hockey's handshake goes back to the early 1950s.

"The earliest Stanley Cup final that I have seen is 1950," he says. "They did not shake hands that year, but a little table was pushed onto the ice with the Cup on it, and the players just kind of hung out in groups of three and four, like a cocktail party almost. They were giving each other best wishes, but it was not the elongated line you see today."

Although the handshake didn't make an encore appearance during the remainder of baseball's post-season, Halligan doesn't see any reason why it couldn't take hold there. "Nowadays, with players moving so freely, they consider themselves one," he says.

Indeed, notes Wolff, young athletes have grown up shaking hands after every contest in youth competitive and recreational leagues, and it's also a staple in high school and college sports programs of all kinds. The few voices heard in opposition to the Cardinals-Dodgers handshake - if you can believe that anyone could oppose such a thing - were those of old-time baseball players. Notably, Nolan Ryan made it clear that handshakes couldn't be a ballplayer's stock in trade.

"After a boxing match, there's so much emotion and it's a hard-fought fight, that's a natural human reaction," Ryan told The New York Times, referring to boxers' post-fight embrace. "In baseball, it may be a three-, four-game series. Maybe next week I have to get them out again. Am I against what happens in boxing or after a football game, where that's the only time you're going to see them? I'm not against it, but baseball is different."

That kind of "curious response," Wolff says, will die out with this generation.

"Players today have great respect for each other, and are all part of the same union," he says. "Some of them were teammates in the minors, and they don't hate each other now that they play on different teams. The whole thing about rivalries is usually puffed up by marketing people."