Volleyball's most famous pro tour is making a comeback on the beach, but will it be enough to lift the game's other levels of competition?

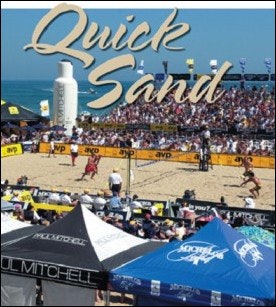

At the risk of stirring up memories of a certain genre of corny 1960s B-movies, it's back to the beach. Thanks to last year's return of the Association of Volleyball Professionals - better known as the AVP - professional beach volleyball is once again on the national stage, pitting world-renowned legends such as Karch Kiraly and Holly McPeak against a crop of young, suntanned studs and bikini-clad beauties, each out to make their mark on the volleyball landscape.

That landscape has changed, though, since the AVP last occupied the spotlight. Although still known mostly for its lifestyle and sex appeal, the AVP itself is an entirely different machine than it was when it was forced to file for bankruptcy four years ago. Over that period, several ownership groups have had a hand in converting the AVP from a players' association to a privately owned corporation, with none playing a greater role in its resuscitation than its original co-owner, Leonard Armato.

Last May, Armato left the sports-agent profession to become the 19-year-old AVP's full-time commissioner and owner. In barely a year's time, Armato has secured big-money sponsorships and television airtime, signed premier male and female talent (the AVP was previously a men's-only tour) and adjusted match rules to harmonize with those of the rest of the world.

At the conclusion of the AVP's second season since Armato's takeover, an early assessment would suggest that his strategy is working: the sponsor list boasts names such as Nissan, Gatorade, Paul Mitchell and Michelob Light, and matches have been televised on NBC and Fox Sports and cable's Oxygen network. But then again, it is early. In the meantime, the remainder of the volleyball world - including players and coaches at the youth, high school, club and college levels - are waiting to see how and if the AVP's return will affect the fortunes of volleyball in the years to come.

If other recent events give any indication of the sport's destiny, things don't look so good. On the college landscape, the University of Massachusetts-Amherst women's program became the second casualty this year and third volleyball program to be cut at the Division I level in the past five years. On the men's side, two Division I programs were eliminated in 2000, at Loyola Marymount and San Diego State, despite the fact that men's volleyball in 1973 brought SDSU its only national championship in any sport.

The news hasn't been much better in the professional ranks. Two professional women's leagues folded as the '90s came to a close: the 12-year-old Women's Pro Beach Volleyball Association in 1998 and the indoor National Volleyball Association after only its second season in 1999.

The failure of these leagues is further evidence of volleyball's lot as the best-liked sport not to make the professional cut. Baseball, basketball, football and hockey (the "big four") hoard so much of the athletic market share that many individuals - fans, athletes and sponsors alike - have no room left for a fifth. And in the rare instances that they do, sports such as golf are better positioned to consume what's left.

And yet, as with soccer, more youths than ever are playing the game at the high school level. According to the National Federation of State High School Associations, 430,582 boys and girls participated in volleyball during the 2000-01 school year, a 20 percent increase in only four years.

Similar growth has been experienced on the junior club circuit, which has been credited with raising the level of play among high school players across the country. Evidence of the popularity of club teams can be found at the well-attended national competitions held for such groups in the high school off-season. In 1985 - the first year it offered an all-girls tournament - the Volleyball Festival fielded 120 teams. At the 19th annual event, held this June, an estimated 10,000 teenage girls on nearly 900 teams from 42 states descended upon Davis, Calif., to compete for the festival's four age-division titles. Those staggering figures just scratch the surface of how many girls are playing junior club volleyball.

During the same week as the Volleyball Festival, USA Volleyball held both a girls' junior Olympic championship event in Louisville, Ky., and a national invitational tournament in Salt Lake City, each with impressive attendance numbers of its own. "For the past five years, we've had a full field of 576 teams," says Kerry Klostermann, executive director of USA Volleyball. "Last year, we had 1,600 teams apply to be in that event. We had to create another season-ending national invitational event to accommodate that demand."

Largely responsible for fueling that demand is the desire among teenage girls to fine-tune their skills to better their chances of playing college volleyball. Club tournaments have replaced high school games as the chief scouting grounds for college coaches - partly because girls' high school and women's college seasons run concurrently, but also because club competitions give coaches the opportunity to see thousands of prospects in one weekend rather than just a handful.

While this recruiting trend has some high school coaches grumbling, it's hard to ignore the newspaper stories from every corner of the nation reporting on high school athletes who make it to the college level and credit years of club volleyball play for their success.

One such story, printed this May in The Oregonian, profiled the Nike Northwest Junior Volleyball Club's 18 Air Elite squad, third-place finishers at this year's Volleyball Festival and regarded as the top club team in the Northwest. Of the Elite's 11 players - 10 of whom are 2002 graduates - six received scholarships from NCAA Division I schools, one plans to walk on at a Division I university and two signed to play at a junior college this fall. "You walk into the gym, and it's like, 'There's Nike,' " the Elite's Lauren Karpstein, who will play at the University of Portland, told the paper. "People know you."

And club players know that more opportunities are out there. In 2000, according to the NCAA, 947 of its member schools offered women's volleyball programs, 304 of them at the Division I level. In addition, the NAIA fielded 260 teams and the NJCAA 299 in 2001.

While women's college programs are thriving, men's teams are lagging behind, says Al Scates, head men's volleyball coach at UCLA. Over a 20-year span dating back to 1981, he notes, only 10 NCAA schools added men's programs, increasing the ranks from 63 to 73 by the year 2000. But, Scates says, the numbers only tell half the story.

He says that an indifference to the plight of men's programs has pervaded the American Volleyball Coaches Association, the professional organization whose members include coaches of high school, club, Olympic and college programs. "When a small university dropped a women's program, the AVCA web site encouraged members to forward a response letter to that college. Everybody was in an uproar," says Scates. "But we lost two men's programs in the past two years, and nobody seems very concerned."

Coaches of men's volleyball programs are most concerned about how scarce scholarships have become (Division I men's teams are each allotted 4 1/2), a trend for which many blame gender-equity requirements.

"We're just trying to hold on to what we have right now," says Scates, who anticipates that this coming season, he'll be forced to cut some of his team's 28 returning members. "I'm going to have to let some of these guys go and they're not going to have any place to play. It's a shame, because they just love to be out there."

At schools lacking a men's varsity team, there is usually a club team in its place. That's the case at 29 California schools, and according to the National IntramuralRecreational Sports Association, at 322 other colleges nationwide. For 18 years now, the men's club circuit has even had its own championship, with anywhere from 130 to 150 teams attending annually. These figures are evidence, at least to Scates, of the demand for men's varsity programs. "Most of those would be varsity teams if their colleges didn't have football teams," he says. "If I ever held an open tryout, I would have 400 or 500 people coming in the gym wanting to play on my team."

For male athletes fortunate enough to land on a college team, there are several post-collegiate playing opportunities, each with its own advantages and drawbacks.

There is the AVP, with its fun-in-the-sun atmosphere and potential for national exposure. But that atmosphere has only enough room for 32 men's and 24 women's two-person teams and while the tour works to get back on its feet, that visibility is still somewhat limited. The earnings potential, too, is a far cry from the 1995 peak of $4.5 million in prize money, dispersed over 27 events. Each of the tour's seven events this year carried a purse of $125,000, divided evenly between the men and women. Winning teams walked away with $14,500, second-place finishers with $9,750 and the other two semifinalists took home $5,825.

At first glance, life on the international circuit may seem far sweeter. Professional volleyball leagues and tours exist worldwide, none as successful as those in Europe. For example, Italy's most prominent professional league, Lega Volley, has 56 men's and women's teams, and is just one of many to lure American players with lucrative, multiyear contracts and opportunities to compete regularly against the world's best players. "A top player in Italy can make $3 million over four years," says Scates. "Virtually every country over there has major and minor leagues, and their players are making good money. It's a good time to go."

But the overseas game isn't for everyone, and that's one of the main reasons why Mike Barry and other officials with United States Professional Volleyball - the latest women's pro incarnation - like their odds for success. "We're trying to create post-collegiate opportunities for women who have done well at that level," says Barry, vice president of league development for USPV, which wrapped up its inaugural season in May. Without such a league for women in the United States, Barry adds, "their college season's over, and that's it."

Pro volleyball startups - especially for women - haven't fared well in recent years, which Barry says is why the league spent two years as an exhibition tour, getting its feet wet against national and international competition. Going into its first season, USPV maintained that conservative approach, starting with franchises in just four cities: mid-sized Rochester, Minn., and Grand Forks, N.D., and large-market Chicago and St. Louis. Those teams - each loaded with former NCAA All-Americans - play 36 matches a year in intimate venues that seat no more than 4,000.

Despite its low profile off the court, Barry says the action on the court is anything but. "It's an arena experience. When people show up, there's smoke, light shows, music," he says. "Besides, they're seeing incredible volleyball - these women are so powerful, so athletic, so graceful. It's a great show. It's good wholesome family entertainment."

Part of that family atmosphere includes USPV players - all of whom, for the first season, signed six-month contracts ranging from $22,000 to $28,000 - going the extra mile to connect with their fans. "After every match, it doesn't matter how tired these women are, they'll put their ice packs on and sit down at tables in the middle of the floor and sign autographs until every fan has one," says Barry. "I've seen them out there for two hours after a match."

While USPV's marketing strategy is certainly a clever move, it's also one that's necessary. Females ages 12 to 20 (USPV's target audience) make up the overwhelming majority of this country's volleyball players. How volleyball fares in the next few years depends not only on their sustained interest in the sport, but just as important, on the development of these players' skills.

That's why USA Volleyball is investing much of its time and resources into programs designed to train the nation's elite to become even better. The organization's regional and national "High Performance" development camps and national youth and junior teams feature 1,600 "highly skilled athletes who are making it a priority to become a member of the national or Olympic teams," Klostermann says.

In recent years, U.S. volleyball has lost some of its luster on the Olympic stage. After at least one American team medaled in three straight Games from 1984 to 1992 (the U.S. has since medaled in beach volleyball, which was introduced to Olympic competition in 1996), neither the men nor women have placed higher than the women's fourth-place finish in Sydney in 2000.

Other than what it sees at the Olympics, the general public doesn't know about the numerous events that occupy the national volleyball teams at other times. "Part of our problem is that we only show up on people's radar screens once every four years," says Klostermann. "The televised volleyball segments are hugely popular, though, and always get high ratings."

USA Volleyball is working to turn that quadrennial excitement into an everyday hook through its grassroots efforts at the youth level. In 1996, the organization formed a four-year partnership with Nike for an initiative called "VolleyVan." The program sent volleyball coaches to conduct free youth clinics in communities with scarce resources to teach the sport. "We went across the country and made about 200 stops at Boys and Girls Clubs, YMCAs, YWCAs, and park and rec departments," says Klostermann of the program, whose secondary goal was to introduce more minorities to volleyball. "It's a fairly Caucasian-dominated sport at this point. We'd certainly like to see more diversity among our participants."

One organization that has taken this initiative several steps further is Starlings Volleyball Clubs USA. Based in a suburb of San Diego, the seven-year-old nonprofit organization provides club volleyball for high school-age girls in inner-city communities. Starlings clubs are established in 36 cities and Native American reservations nationwide, serving approximately 3,000 girls this year. Clubs in most cities do not charge fees, with the San Diego club - which charges its players $35 per month - a notable exception.

According to Byron Shewman, Starlings' founder and executive director, many of these girls come from families that cannot afford clubs, which can charge upwards of $5,000 a year per player. "They're becoming very elitist and eliminating opportunities for about 80 percent of the girls," he says. "Coaches don't even look at high school girls anymore; they don't go to their tournaments. I don't begrudge them too much, but I see scholarships going to a lot of girls who can probably already afford to go to college."

Some Starlings "graduates" are making it to the college ranks, however. Shewman estimates that more than 30 former Starlings players have received college volleyball scholarships, many of them at traditionally black universities such as Morgan State, Grambling State and Hampton.

That number is likely to increase with the rapid growth of the after-school Little Starlings and Junior Starlings programs, aimed at girls ages 9 to 14. "We just want to give kids a chance to do something positive," Shewman says. "Volleyball's a team sport that promotes a lot of social interaction. I think those sociological values sometimes get overlooked."

Instilling those values in youths is a fundamental goal of the United States Youth Volleyball League, another California-based nonprofit. For five years now, the USYVL has run free eight-week volleyball clinics in the spring and fall for youths ages 8 to 14. Modeled closely on the American Youth Soccer Organization, the USYVL's clinics are coed and are run by a site director, with assistance from trained clinicians and volunteer coaches. This year, clinics were held at 31 sites across the country, nearly all of which are outdoors.

"We do that because on one soccer field, you can have 216 kids playing as opposed to indoors, where basically you can get 36 kids in a gym with three courts," says Randy Sapoznik, the USYVL's executive director. This strategy has helped the organization serve more than 23,000 youths since its inception. "Space is at a premium, but it also works for exposure. People are more likely to get involved playing volleyball because they see us outdoors."

Simple logistics render that sort of exposure impossible at the USYVL's indoor sites in Chicago and Rochester, Minn., but that hasn't curtailed offers of support from USPV franchises in those cities. The USYVL has partnered with the pro teams in an educational role model program. On the first day of spring practice, Minnesota Chill players visited youths at an indoor clinic in Rochester, giving skills demonstrations and signing autographs. "It makes a world of difference when children get to have a pro athlete come to them," says Sapoznik. "It also really impresses the parents when they see how volleyball is played at the highest level."

An increasing number of those parents are former volleyball players who didn't have the opportunities to play after college and are eager to support efforts by groups such as the USYVL and USPV to grow the sport, says John Dunning, head women's volleyball coach at Stanford University. "We're just starting to see moms get to the age where their kids are playing high school, juniors and college volleyball," he says. "There are almost no grandmas out there who played in college."

True, volleyball didn't take root on a large percentage of the nation's college campuses until the 1970s. As the years progressed and college teams became more commonplace, high school teams and club programs began to sprout up, as well. Says Dunning, a former high school and club coach, "When I started my first club team in northern California in 1976, it was the second club in the state. Now there are more than 600 in California alone. That's tremendous growth."

Dunning says the growth will continue as volleyball programs at all three levels approach the 50-year mark. "We're still a little fragile yet. It's just going to take time," he says. "When we involve more than one generation that's done it, though, the foundation is going to become solid enough for the sport to really grow."