Sovereign Immunity Saves a University's Employees

An increasingly troublesome area of sports litigation occurs as a result of injuries suffered by spectators at sporting events when fans rush the playing field. Plaintiffs in lawsuits against public universities must jump two hurdles to be successful in these types of cases - negligence and sovereign immunity. Of these, sovereign immunity is often most vital to the success of a case, since it typically must be addressed first to withstand a motion for summary judgment.

Sovereign immunity is based on the concept that a state must give its consent to be sued. One of the reasons for its development was that, it was theorized, the state could do no wrong. Because the state was presumed to be acting on the public's behalf, there was no need to allow the public to sue the state. In addition, any damages awarded in a lawsuit would be paid out of taxpayer funds - and many people believe that limited government funds should be expended only for public purposes. Some believe, further, that by allowing people to sue the government, the public will be held responsible for the wrongs of government employees.

Whatever the policy behind sovereign immunity, most states allow a number of exceptions to the general rule of immunity. In states governed by a sovereign immunity statute, a distinction is often made between governmental and proprietary activities. A governmental activity is one that can be performed only by the state and, as such, is commonly protected from lawsuits on the grounds of sovereign immunity. Since education is considered a governmental activity, public universities fall under the purview of sovereign immunity.

Universities have dealt with this issue for some time. For instance, in Cantwell v. University of Massachusetts [551 F.2d 879 (1st Cir. 1977)], a gymnast was injured as a result of an assistant coach's negligence. The court dismissed the action against the university based on sovereign immunity. The court provided that the case against the assistant coach was dismissed on the "ground that, as a public official, he was immune from liability for nonfeasance." In Shriver v. Athletic Commission of Kansas State University [222 Kan. 216 (1977)], the court held that the carrying of a football team was proprietary in nature and, therefore, sovereign immunity would not bar a lawsuit against the university.

A more recent case shows how the courts' view of sovereign immunity may be changing.

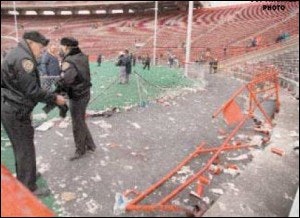

On Oct. 30, 1993, University of Wisconsin fans from several student sections attempted to rush the Camp Randall Stadium football field after a Wisconsin victory over the University of Michigan.

Security officers initially tried to prevent the surge of spectators; in addition, spectators were held back by an immobile, 4-foot-high chain-link fence ringing the field, as well as latched metal gates that were in place to keep fans from interfering with players heading off the field into the players' tunnel. In the chaos that followed, a railing collapsed, sending fans tumbling to the ground, where they were trampled, while scores of spectators were crushed against the fence. Further tragedy was averted when security unlatched the gates and allowed fans to spill onto the field.

In the lawsuit that followed, Eneman v. Richter [577 N.W.2d 386 (Wisc. 1998)], a group of fans sued the university, Athletic Director Pat Richter and many other UW employees, including the chancellor, the chief of police and the facility and events coordinator. The plaintiffs asserted that they would not have been injured if the gates blocking off egress from their seating sections had not been closed. The defendants claimed, successfully, that they were exempt from liability due to sovereign immunity.

The case focused on the UW chief of police largely because the court held that the chancellor and athletic director were not responsible for crowd control. The police chief had implemented a policy for crowd control at football games, the general strategy of which was to prevent injury to people, including officers, band members and fans.

To decide the case, the court looked to public officer immunity, which it found to be very similar to sovereign immunity. The court provided that "public officer immunity precludes personal liability for discretionary acts performed within the scope of a state officer's official duties."

Generally, state employees are immune from personal liability for acts of negligence performed within the scope of their employments. However, there are exceptions that vary depending on state law. The court in Eneman discussed two such exceptions - the negligent performance of a purely ministerial duty, and the negligent performance of discretionary acts that are non-governmental in nature.

Public officers are immune from liability for discretionary acts, not ministerial acts. The court provided that a "public officer's duty is ministerial only in the limited circumstance when the duty is: absolute, certain and imperative, involving merely the performance of a specific task when the law imposes, prescribes and defines the time, mode and occasion for its performance with such certainty that nothing remains for judgment or discretion." However, a public officer has a duty to act, which is ministerial, when he or she knows of an obvious danger.

In the Wisconsin case, the defendants knew there was a potential for fans to rush the field at the conclusion of a game. The court concluded that there was a known danger to create a ministerial duty on the part of the defendants. However, the court concluded that the decision dealing with what type of plan to formulate, as well as the implementation of that plan, were discretionary acts. The defendants, therefore, were shielded from liability.

The plaintiffs also argued that the defendants' acts were non-governmental in nature and, therefore, an exception to immunity. However, the court provided that the concept of a non-governmental act exception to immunity applies only in municipal liability situations (in Wisconsin, there is a general rule of municipal liability and an exception of municipal immunity). Because the court was dealing with state officer immunity and not municipal immunity, the concept could only apply in cases of medical malpractice. This case did not deal with a plan implementation that required highly technical, professional skills, as in medical malpractice cases. Therefore, the court held that the defendants' activities were governmental in nature.

The court concluded that neither exception to immunity applied to the facts, and the court of appeals upheld the lower court's decision granting summary judgment to the defendants. The plaintiffs could not sue Wisconsin officials for negligence.

An appeal to the Wisconsin Supreme Court in Eneman v. Richter [589 N.W.2d 414 (Wisc. 1999)] yielded an interesting outcome. The Supreme Court, in a less-than-definitive opinion, effectively upheld the decision of the appeals court even though its justices were split - three justices would affirm the decision, while three justices would reverse the decision. (The chief justice did not participate in the decision.) What is particularly noteworthy, aside from the fact that the appeals court's decision came so close to being reversed, is that it brings one more state closer to ending sovereign immunity altogether. Several states have done away with the concept, and many states that have kept sovereign immunity have enacted additional exceptions. It appears that to some extent the theory is waning.

Several important lessons can be taken away from the Eneman case:

• Universities should have an appropriate crowd-control policy in place. Wisconsin's policy likely saved employees from liability because the employees knew of the danger of fans rushing the field and took steps to abrogate that danger.

• The court commented on the often difficult and constantly changing decision-making process of crowd management. The court stated that "by its very nature, the way the plan was effected had to change from moment to moment because the plan was responsive to the crowd." The court further noted that "reacting to the crowd also constituted the exercise of discretion." The court recognized that any crowd-management plan would have to change and adapt to the crowd's response.

• As noted above, the court concluded that the athletic director was not responsible for crowd control. This eliminates personal liability on the part of the athletic director, at least in situations like this one. In situations in which the athletic director has a more hands-on role in crowd control, the athletic director may risk personal liability for negligence.

• Sovereign immunity is only available as a defense to public colleges and universities, not private ones.

Above all, university officials should remember to put policies in place to prevent injuries. These types of cases are costly to litigate, particularly when they generate multiple appeals. Even in a state where sovereign immunity holds sway, a plaintiff may attempt to bring a case under an exception to sovereign immunity; university officials should act, therefore, as if there is no sovereign immunity coverage.

Attorney Glenn M. Wong, editor of "Sports Law Report," is a professor in the Sport Management Program at the University of Massachusetts, Amherst, where attorney Karen R. Skinner is a graduate student.