The NCAA Retains the Right to Prevent Student-Athletes from Following its Moneymaking Lead

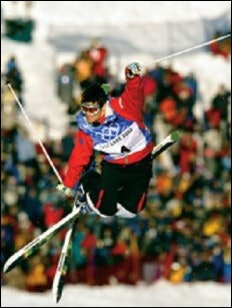

In an era of increasing athletic specialization, two-sport athletes stand out among their peers. Athletes of great accomplishment who have commendable academic credentials and elite athletic qualifications in markedly divergent sports are particularly noteworthy. Such is the résumé of Jeremy Bloom, the 20-year-old football player from the University of Colorado at Boulder who deferred his first year of intercollegiate athletic participation to compete as a member of the 2002 United States Olympic team in the sport of freestyle moguls skiing. He placed ninth in the Salt Lake Games, eventually finishing the season as the World Cup champion.

As a world-class athlete, Bloom was offered and accepted standard forms of remuneration consistent to his sport and his level of competitiveness. His earnings included money from various events and endorsement contracts with companies such as Oakley and Under Armour. As skiers customarily bear the burden of financing the high cost of travel and training (a price tag that can easily exceed $100,000 per year), Bloom's ability to generate funds through his athleticism was, and remains, central to his ability to compete in the sport of moguls skiing.

In January 2002, anticipating Bloom's desire to matriculate in the fall and play football for the Buffaloes (while not abandoning his moguls career), the University of Colorado sought clarification from the NCAA regarding his eligibility status. At issue was whether Bloom could continue to receive prize money and endorsements for his skiing (and accept monetary compensation for work as an actor and model) while preserving his NCAA football eligibility. Based on the NCAA's provision that an athlete may be a professional in one sport and an amateur in another, Bloom was permitted to accept prize money from his races. However, the NCAA restricted him from accepting compensation for endorsement contracts based on his (broadly construed) "athletics ability." The NCAA argued that to do so would jeopardize Bloom's eligibility because acceptance of such compensation would violate the principles of amateurism that (purportedly) serve as the foundation of the NCAA's purpose.

Following the NCAA's decision (and an unsuccessful appeal), Bloom initiated an action against the NCAA, seeking injunctive and declaratory relief. The plaintiff's attorneys argued that the NCAA violated its contractual obligation to Bloom by devaluing "its own constitutional directives to foster the educational development of student-athletes and promote their welfare."

The decision against Bloom, written by Judge Daniel Hale of the Boulder County Circuit Court, reflects the ambivalence of the courts toward the NCAA's internal decision-making capacity. Hale disagreed with the NCAA's assertion that Bloom was not a third-party beneficiary to the contract of membership between the NCAA and the University of Colorado (and therefore that there were no grounds for breach of contract). According to Hale, athletes are intended to be third-party beneficiaries of the contract between the NCAA and its member schools, given the degree to which the NCAA emphasizes its educational purpose in regulating athlete eligibility, the activity of agents relative to athletes, and compensation for participation in college sports.

Hale also found that Bloom would experience irreparable harm as a result of the NCAA's action, and that there was no adequate legal remedy available to him. Hale made a point to mention that while neither the NCAA's rules nor administrative process were arbitrary nor capricious, the NCAA had the ability (though it had failed) to arrive at a more amenable accommodation with Bloom that acknowledged the uniqueness of the circumstances.

Yet, Hale determined that Bloom's breach-of-contract assertion did not have a strong likelihood of succeeding on the merits. Hale also noted that he was prohibited from substituting his own judgment for that of the NCAA.

In this case, as in many others where the NCAA has prevailed over an athlete, great weight was given to the NCAA's assertion that its primary purpose is the promotion of amateurism. As the NCAA Constitution states, the association's goal is to "maintain intercollegiate athletics as an integral part of the educational program and the athlete as an integral part of the student body and, by so doing, retain a clear line of demarcation between intercollegiate athletics and professional sports." But does the NCAA really set up a firewall of protection between college athletes and commercial interests, or is the NCAA's rhetoric a smokescreen used to obscure the fact that it is running a professional enterprise?

Challenges like Bloom's provide ample opportunity to explore this intriguing notion in greater detail. How can the NCAA effectively argue that its rules exist to protect the welfare of athletes when Bloom is clearly a casualty, and not a beneficiary?

The concept around which all NCAA bylaws are constructed is that of the "student-athlete." Yet, as Walter Byers (the NCAA's first executive director) pointed out in Unsportsmanlike Conduct: Exploiting College Athletes, it was a term strategically devised and adopted by the NCAA to deflect attention away from the threat created when members of the NCAA agreed to accept athletic ability (rather than academic performance) as a criteria for athletes to receive grants in aid. Members knew that scholarships awarded on the basis of athletic ability constituted "pay for play," and a contract between an employer and employee. The history of athletic scholarships suggests that decision-makers within the NCAA are not as interested in educational issues as they are in ensuring that the workforce that they do not wish to have exploited by outside organizations remains available for exploitation from within.

It bears noting that the NCAA claims that it seeks to treat athletes like all other members of the student body, while at the same time subjecting them to limitations that would be indefensible if applied to other students. Bloom pursued his case with this in mind. The University of Colorado also documented the educational aspects of the appeal, asserting that Bloom "should not be prohibited from gaining experience in his chosen career simply because he is an elite athlete who wishes to play college football."

The NCAA's stated commitment to the education of students is tested in the language and tone of the response it submitted to the court in this case. Bloom was represented as a headstrong, willful, greedy and perhaps poorly advised young man rather than a mature adult. In an accusatory fashion, the response chided the plaintiff for focusing on money instead of education, characterizing the "entire lawsuit" as one based on the "plaintiff's desire to be a professional actor/advertiser while also being an amateur athlete." Indeed, the association came dangerously close in its defense to mocking the legitimate aspirations of a young person growing up in a consumer culture where modeling and appearing on TV are certainly attractive (and lucrative) options.

In short, the NCAA's response could be read not as the work of an association interested in student welfare and education, but as reflecting the attitude of a corporate entity concerned about its bottom line. It is this contradiction that may eventually lead to the NCAA's demise. In the end, the organization that denied Jeremy Bloom's educational right to pursue acting and modeling opportunities while competing within the NCAA's billion-dollar league may become a casualty of its own hypocrisy.