As the lure of downtown living pulls more residents from the suburbs, inner-city recreation departments take measures to accommodate the new arrivals

With Super Bowl XL coming to town in 2006, Detroit is getting ready for some football. But the cranes and jackhammers chipping away at the downtown facade aren't simply to prep the city for its role on the NFL's biggest stage. Often cast on television and movie screens as a haven of crime and corruption (think the futuristic thriller "Robocop"), Detroit is in the midst of a major renaissance. Rather than view the pro football extravaganza solely as an opportunity to generate tourism revenue and showcase the city's new sports facilities, Detroit Mayor Kwame Kilpatrick is spearheading an ambitious downtown revitalization campaign in an attempt to lure residents back to the heart of the Motor City.

Those following City Hall's lead in Motown's second coming include developers (who are rehabbing long-vacant warehouses into trendy apartments, condominium lofts and corporate offices) and entrepreneurs (whose hip new restaurants, bars and retail shops are popping up on virtually every downtown street corner). Catching on, too, are recreation professionals, who likewise see a demographic that has been labeled the "creative class" -- young, upwardly mobile professionals such as writers, designers and high-tech workers who crave arts, culture and recreation -- as being crucial to the rebirth of the inner city.

"Recreation is an amenity. Restaurants are amenities. The arts are amenities. The quality of the landscape - streets, sidewalks, parks - all of those things are amenities that make an urban environment attractive," says Reid Thebault, president and CEO of the YMCA of Metropolitan Detroit. "The city's leaders have taken a broad look at all the things we can do to attract people, both from an employment as well as a residential standpoint. Ultimately, that's the goal - to get more people living in the inner city, because you need people to have a community."

This month marks the Detroit Y's most visible attempt yet to rebuild the inner-city community as it breaks ground on a $32 million, 85,000-square-foot flagship facility, signaling the organization's return to that area after a four-year absence. (The Y's downtown predecessor, a 90-year-old facility, was demolished in 1999 to accommodate the construction of the Tigers' Comerica Park.) The five-story facility, located at the center of Detroit's business district, will feature a natatorium, a track, a center for performing arts and literacy, and a wellness center.

Thebault expects that initially most of the Y's programs will cater to young professionals, but as more people move to downtown Detroit, there will eventually be a greater balance between offerings for individuals and families. "Like any downtown, it's a microcosm of the region," he says. "The working daytime population will be a target audience, typically for fitness and wellness programs. Youths and seniors will be particularly attracted to the arts programs. We also have a child development center that will be supported by people with children who live downtown, as well as by downtown employees and their children. The membership mix will be really similar to a suburban branch, although maybe a little stronger on individual memberships than families, as the residential population continues to grow."

Of course, not all will be attracted to the Y's services. Detroiters who prefer a park stroll to a treadmill or dance class can look forward to enjoying Campus Martius Park, a two-acre park straddling Detroit's historic surveyor's "point of origin" and located just blocks away from the new Y. The park -- which is owned by the city but is being built and managed by a nonprofit conservancy -- will offer free music concerts, an ice skating rink in the winter and a café when it opens midyear 2004.

All throughout Detroit, a major parks beautification campaign is under way, something that according to Lee Stephenson, interim director of the Detroit Recreation Department, was long overdue. "In previous years, the maintenance was terrible. They couldn't even cut the grass; it was three, four feet high all through the summer," says Stephenson, who was hired nearly a year ago by the department with the specific purpose of making its parks more accessible and appealing. "We've made great strides on getting the grass cut and beautifying the parks; there are more flowers and welcome gardens throughout the system. Hopefully, we'll be able to attract more people back to the parks system, not only people from the inner city but from the suburbs, too."

Sharing Stephenson's optimism are recreation professionals in metropolises across the country. They, too, recognize that urban parks and recreation departments are going to be heavily counted upon to help inner cities return to their glory days and shake the negative stereotypes that have long plagued them. "As a whole, urban areas are changing the way they do things," says Darrick Nicholas, chief of media relations and communications for the D.C. Department of Parks and Recreation. "More people are moving back into the city, not only in D.C., but also in Chicago and New York. This means that services have to be upgraded to handle the growth. Some cities may be slow at first to decide whether or not to do it, but eventually all will have to do this kind of thing. It's a great time to be here because there's a lot of change."

If this country is indeed on the verge of a population shift back to the inner city, it will mark an end to five decades of significant flight to the suburbs. Seemingly nothing has been able to curb suburban migration, the reasons for which are as varied as the people who have been heading for the hills en masse since the early 1950s - whether it be in search of a larger home, a better school or a safer neighborhood. In recent years, however, people are finding that the draws of suburban life aren't as good as advertised.

These days, living in the suburbs means using congested "expressways" and sending one's children to schools that are oftentimes just as overcrowded. Also, the suburbs haven't been able to entirely escape crime, as last year's Beltway sniper episode - which terrorized the affluent Capital-region counties of Montgomery and Prince George's, Md., and Fairfax, Va. - demonstrated in alarming fashion.

Still, streets in those communities are considered by many to be much safer than the ones that traverse the region's hub, Washington, D.C. Those who remain critical of the nation's capital continue to see and talk about nothing but the negatives, despite its leaders' efforts to raise the city's stature. Take, for example, a July Washington Post article that reported the low-income Benning Terrace neighborhood in southeast Washington as so devoid of recreational opportunities that during the summer, youths resort to stealing cars for joyrides. "Where is the recreation for the older kids?" 16-year-old neighborhood resident Cordario Coleman asked Post reporter Simone Weichselbaum. "We have nothing to do."

In response to that community's concerns, D.C. Parks and Recreation has since stepped up its presence in the neighborhood by extending its "Roving Leaders" mentoring program, repairing two outdoor basketball courts and implementing two mobile recreation programs, one of which offers skateboarding and another that provides arts and crafts. On a broader scale, the recreation department has undertaken an ambitious six-year, $122 million initiative to renovate outdated and rundown facilities, add programs and protect green spaces.

This fall will bring the opening of five new recreation centers, including one located downtown and several others in low-income neighborhoods. Around the same time, the Capital East Natatorium, site of the department's annual Black History Invitational Swim Meet - a two-day event that attracts young minority swimmers from 25 cities across the country and the Virgin Islands - will reopen after undergoing a major renovation. Additionally, in August the department debuted a new software system that allows residents to reserve facility space and register for programs online. It's the first time D.C. Parks and Recreation has used software automation to streamline administration. "They're all going to be fantastic facilities, and more are on the way," says Nicholas. "After a certain amount of years, you really have to reinvest."

That may be true, but some cities are more reluctant than others to make that sort of commitment, particularly now that municipal governments everywhere are expected to do more with less. Marrell Harmon, for one, doesn't think tighter budgets should be used as an excuse to let good recreation programs and the urban communities they serve go by the wayside. In Richmond, Va. - where the inner city is predominately minority-populated - Harmon is having an especially difficult time convincing his civic leadership of the need to invest more in the youth tennis program offered by the city's Parks, Recreation & Community Facilities Department. For eight weeks from spring to summer, as many as 350 Richmond youths ages 6 to 17 receive tennis lessons at 11 sites throughout the city.

Given those impressive numbers, it's obvious that getting kids to participate isn't the problem - it's keeping them involved in tennis once the summer program ends. "Some of the kids, especially when they see black players like Serena and Venus Williams win, get really excited," says Harmon. "But that wears off after a while. We'll have some kids who are really good, but when the program's over for the summer, that's it. We lose them to something else."

That's because, according to Harmon, there is no indoor tennis facility in Richmond where youths can further hone their tennis skills in the winter and spring seasons. He hopes the city will eventually buy into his proposal to establish a facility similar to the Arthur Ashe Youth Training Center in Philadelphia, which provides educational programming in addition to tennis instruction. (Richmond is, after all, the birthplace of the late tennis player and activist.) "We don't need an elaborate building, all we need is a building where we can play tennis and teach kids," he says. "I guarantee you we will have kids who know how to play. I'm not necessarily saying our kids are going to win the city tournament, but we're going to have kids who know tennis and tennis etiquette."

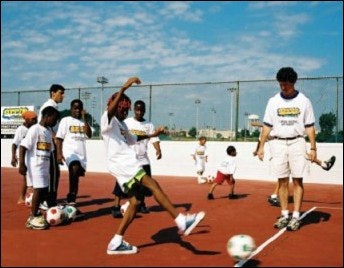

Likewise, Phil Hill's goal isn't necessarily to turn Atlanta's inner-city youths into future champions. "Most of these kids have nothing to do, so they hang around on the streets and get into trouble," says Hill, chairman of Soccer in the Streets, a grassroots effort that teams his nonprofit organization with recreation departments to teach soccer to Atlanta's inner-city youths on modified tennis courts called "StreetBoxes." "The main goal of our program is to positively change these kids' lives - it just happens to be through soccer."

That positive change comes in the form of Soccer in the Streets' Positive-Choice ™ track, which teaches participants 10 soccer skills, each of them relating to one "life skill." For example, passing is paired with communication, ball control with self-control, shooting with goal-setting. Youths are awarded points for mastering each skill, but can also be penalized for exhibiting negative behavior. "Points are taken off if they're sent off the court, if they get reprimanded by the coach, display violence or if their report cards aren't handed in on time," says Hill. "As they become more involved in our program, their attitudes change."

Soccer in the Streets' adult staff and volunteers are counted on to provide at least one structured session a week, but Hill credits the program's more organic development for gradually creating mentors from among the older youth participants. "One kid who started with us last year has already taken his referee's course and gotten certified as a referee. He uses that to earn extra money on the weekend. Now a lot of the younger kids look up to him," he says. "As the program grows, the younger kids will get taught by the older kids, and ultimately, we want to become obsolete so the kids are doing their own thing. This is a longer-term view, but it will happen. It happens in the rest of the world. If you provide the infrastructure for them, it will run itself."

Providing that infrastructure meant convincing recreation departments in Atlanta and East Point, a low-income community, to donate tennis courts that, according to Hill, had seen so little use they were overgrown with trees. It cost about $20,000 to refurbish each of the courts and outfit them with dasherboard systems to form the "box." Soccer in the Streets has identified 18 other sites throughout Atlanta and depending on the available funding, hopes to open more StreetBoxes in the future. "Our goal is to put a soccer ball within reach of every innercity kid," Hill says. "Until we really start investing in these communities with programs like this, the sport won't penetrate the inner cities. Everyone keeps trying to force the middle-class, "soccer mom" soccer model on the inner city. It doesn't work. You can't transport these kids out of their communities and take them to the field. You've got to go where they live and give them something that's made for them."

Officials at the Detroit Y couldn't agree more, and are confident that the new downtown facility will draw not only residents from the inner city but also those who live in communities on Detroit's fringes, or "edge cities." "A lot of the close-in suburbs really relate to downtown because it's easier to get to downtown than to other parts of the region, even suburbs of suburbs," says Thebault, giving credit to easily accessible freeways and arteries.

Nicholas has found that commuters frustrated with Beltway traffic hampering their efforts to promptly pick up children from suburban recreation programs are now trusting D.C. Parks and Recreation to provide those services. "If you're a parent and you work in the district but you live in Maryland, you can put your kids into our programs as opposed to putting them in a program in Maryland and having to fight the traffic, hoping to get there by six o'clock because that's when the doors close," he says. "More parents, not only inside the city but also outside the district, are looking at our services."

With all that extra attention on D.C. Parks and Recreation and other departments in urban areas, it would seem that now is the time to rebuild images and turn common perceptions of the inner city from negative to positive. Asheville (N.C.) Parks and Recreation has jumped on the opportunity by creating a Cultural Renaissance Program, which introduced approximately 300 inner-city youths to the visual arts. The program began last summer and was highlighted by the Recreation Center Mural Project, during which children, under the guidance of a local artist, spruced up the facade of the otherwise nondescript W.C. Reid Recreation Center. "The summer arts program, in which professional artists were residents at several of our community centers, was based on a multidisciplinary approach of utilizing the arts to address social issues," says David Mitchell, superintendent of the department's Cultural Arts Program. Through poetry, for example, "kids can make a statement about the conditions of their communities and how they would like to see those conditions changed or improved."

Participants are also allowed to express themselves through music, theater and dance - exciting alternatives for a demographic that often sees sports as the only means by which to carve out a path of success. "There's more to it than basketball," says Wanda Hawthorne, director of the Reid Recreation Center, located in one of Asheville's poorest neighborhoods. "A lot of our kids have great dancing skills, great visual-arts skills that need to be developed. We're here to show them that artists make money, too. Art's not just something people do for fun; it can be a profitable business, as well."

This year, as many as 450 youths participated in the program, which has been expanded from being a solely summertime offering to one that operates year-round. Mitchell believes that this move will bring about community benefits that reach far deeper than the Reid Center's fresh coat of paint. "The gratitude and applause that these kids get from participating and performing increases their self-esteem and motivation during the school year, which is evident in their ability to be focused, goal-oriented and show a serious commitment to the community," he says. "We're keeping a great number of kids away from negative elements in our community. Of course, you can't catch all of them. But by and large, we're hoping to create a climate or a generation of youths who would rather spend their time participating in positive programs."

Thebault and his staff are working to create a similar atmosphere in Detroit and won't be deterred, despite the uphill public-relations battle facing them. "You turn on the news and whether it's in Topeka, Kan., or New York or Detroit, you hear about the latest assault and then there's the perception that that community is crime-ridden. Unfortunately, it seems it isn't part of the media industry to talk about all the good things that are happening," says Thebault, reflecting upon one of his first tasks as the Detroit Y president, nearly nine years ago. "When we were recruiting for Y staff, we had a challenge attracting people to come and interview. What we found was that if we could get them to come here and look around, and see the city and the neighboring communities, we were extremely successful in getting them to accept offers. We just needed to get people to come and see.