Schools and coaches should insist on certain provisions within their contracts

Now that the dreams of August and September have given way to the harsher realities of November, a number of colleges and universities across the country will begin the yearly courting process involved in hiring a new football coach. This process, which is as old as college football itself, usually goes fairly smoothly. For example, the coach at School A is either fired or resigns to accept a better position. In order to replace the coach, School A hires the football coach at School B. School B in turn hires the coach at School C. In fact, the process is so ingrained in college football and other big-time sports that schools usually build into their coach's contract language expressly allowing the school or the coach to buy out the contract for a specific monetary sum.

As with all relationships, however, problems occasionally surface during courting - especially when School B does not want to lose its coach. An interesting example of some of the difficulties that can occur when a coach walks away from a contract and accepts another position is Northeastern University v. Brown, a case that was settled out of court prior to trial.

The trouble started last January when head football coach Mark Whipple, disappointed with the University of Massachusetts' decision to delay a move up to Division I-A, decided to leave the university and accept a job with the Pittsburgh Steelers as quarterbacks coach. At about the same time, Don Brown, the head football coach at Northeastern University, was contacted by a third (unnamed) college concerning its head coaching job. Brown told Northeastern's athletic director, David O'Brien, that he wanted to speak to the other school about the position. Not wanting to lose his head coach, O'Brien convinced Brown to forgo the interview opportunity and stay at Northeastern. In return, O'Brien agreed to give Brown a contract extension through June 2009, which included substantial salary increases for Brown and his staff, as well as other substantive program enhancements.

Before the contract could be drafted and signed, however, the University of Massachusetts called O'Brien, seeking permission to speak to Brown about its open coaching job. Northeastern, citing its contractual right with Brown and the fact that it had just agreed on an extension, increased compensation and other program enhancements, refused to grant the University of Massachusetts permission to speak with Brown.

The University of Massachusetts claimed that the objective of the phone call in question was not to ask O'Brien for permission to speak with Brown. Rather, the university claimed, it was simply a courtesy call to inform O'Brien that, based upon the school's prior relationship with Brown, he would be one of the candidates they would consider to fill their head coaching position. As the university noted, not only did Brown have ties to its football program (having worked on Whipple's staff as defensive coordinator before accepting the Northeastern job), he was also a successful coach within the same geographic area.

After initially telling O'Brien that he was offered and turned down the head coaching position at UMass, Brown on Feb. 9, 2004, tendered his resignation to O'Brien. Later that same day, both Brown and UMass announced that Brown had agreed to become the university's new head football coach.

While Brown's hiring was celebrated at the University of Massachusetts, it was criticized by Northeastern officials, who in response went to court seeking an injunction preventing Brown from taking the head coaching job or serving in any other capacity at the University of Massachusetts. It should be noted here that under contract law and the theory of specific performance, there was nothing that Northeastern could do to force Brown into honoring his contract and returning to Northeastern. Because a court order applying the specific performance theory (which would force people into fulfilling their contract requirements with regard to the delivery of products and other unique items) could be interpreted as involuntary servitude, the courts have deemed such remedies to be in violation of the Thirteenth Amendment of the United States Constitution. Therefore, the best Northeastern could do was to prevent Brown from taking another similar position at another institution.

In granting Northeastern an injunction, Suffolk Superior Court Judge Thomas E. Connolly ruled that "there was no question Brown willfully and intentionally breached his contract with Northeastern. He signed his contract and straight-out violated it." Connolly also criticized the University of Massachusetts for its conduct, ruling that "there also appears to be no question that UMass actively induced the breach when it had been told of the restrictions on Brown's talking to other potential football employers and of his existing, long-term contract with Northeastern."

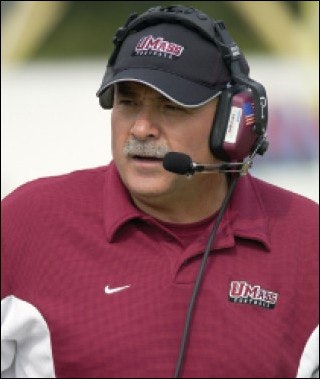

Before Brown could file an appeal challenging the injunction, however, Connolly ordered that the injunction against Brown be lifted and that the two schools work out an acceptable agreement within 30 days. The decision, which came just days before UMass was scheduled to begin spring football practice, allowed Brown to begin coaching football at the University of Massachusetts. A full agreement between the two schools was finally reached in May, under which Brown was barred from coaching on the sideline for the first three games of the 2004 season. (Interestingly, the agreement allowed Brown to be in the stadium coaches' box, just not on the sideline.) In addition, UMass was also required to pay Northeastern $150,000 and make a public apology.

While it is difficult to determine if anyone wins in a case like Northeastern University v. Brown, the case is a good reminder that coaching contracts are legally binding agreements. It is essential, therefore, that schools and coaches protect themselves by including certain provisions within their contracts. For example, a buyout provision would have allowed Northeastern or Brown to terminate the contract upon the payment of a specified amount of money. This type of provision would not only have helped Northeastern in the current case, but could also be used if the school wished to terminate Brown's contract before it expired.

Arbitration agreement, a clause stipulating that if any dispute arises under the contract the issues will be dealt with through arbitration, is useful because it keeps the case out of the courts and allows for a speedier conclusion. For example, in the current case, if the matter had gone to an arbitrator, Brown may have been able to assume the coaching position at UMass sooner.

Finally, schools can also protect their interests by including covenants not to compete (non-competition clauses) into each coaching contract. For example, if Northeastern wanted to keep Brown from going to a school in the same football conference, the school should have included such a clause in his contract. Such a clause would have legally prohibited Brown from accepting another head coaching position at any school in the same conference for a specific number of years after leaving Northeastern. It should be noted that while courts will uphold such clauses, they would strike down any clause that is too restrictive in scope or time, since it unfairly restricts the coach's future earnings and employment possibilities.