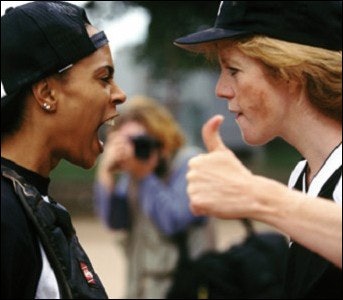

Game officials seek a "safe haven" following a spate of confrontations

Gloria Erkins, principal of Vincent High School in Milwaukee, barged into the officials' locker room after her school's boys' basketball team dropped a 59-50 decision to Bradley Tech in January. Without introducing herself to the two referees who worked the game, she questioned them about a second technical foul called on Vincent coach Tom Diener, which led to his ejection.

When confronted by Erkins, the official who ejected Diener told her he didn't want to discuss the issue and asked her to leave the building by calling for security, according to witness reports published in the Milwaukee Journal Sentinel. After Erkins was removed, Vincent's assistant principal and athletic director Ruben Bivens asked the referees to explain their actions. The one who requested Erkins' removal then allegedly called Diener a "jerk" and said the principal behaved loudly. As of this writing, the incident was under investigation by Milwaukee Public Schools.

For years, referees have been trained locally and nationally in how to respond to confrontations with players, coaches and fans. But the Vincent incident crosses the line into uncharted territory, says Barry Mano, president of the National Association of Sports Officials and a former longtime basketball referee. "Being confronted by the top administrator, who has purview of the entire building - that's something new," he says. Adds another veteran game official, "We expect the administrators to be our allies."

Granted, many principals have cornered referees and umpires after a game to ask questions or request clarifications. But the discussion usually ends after a quick explanation. Erkins' actions have struck such a chord with game officials - who consider their locker room a "safe haven," according to Mano - that NASO plans to develop written guidelines addressing how both game officials and school administrators should conduct themselves in situations similar to the Milwaukee case. Discussions will be in full bloom June 21-23 at NASO's "Sports Officiating 2003" conference in Portland, Ore., a two-and-a-half-day session with the theme of "Accountability in Sports Officiating."

Erkins' actions have reinforced the need for school officials - both athletic directors and school administrators - to protect their game officials, particularly in the moments immediately after a game. "We are always concerned about officials' safety, because an incident can blow up on you at any time," says Jay Cornils, athletic director for Pueblo (Colo.) School District 60, and a 30-year veteran of officiating football, basketball and track. "As an administrator, I need to be neutral and treat my guests like royalty, supporting all three groups - the two teams and the officials."

The four high schools in Cornils' district, which often play games at larger independent sites, employ personnel to ensure that game officials are made to feel welcome and secure. They take a series of precautions that range from simply placing the referees' locker rooms away from the traffic flow of players, coaches and fans, to increasing the number of security personnel and tightening security procedures for intense rivalries. That's why ugly incidents with game officials are rare under his jurisdiction, Cornils says.

To help prevent a major incident between officials and anyone else, Mano, Cornils and other officiating experts suggest offering the crew a key to their locker room. Usually, it's a duplicate key, in case the athletic director or some other administrator or staff person assigned to the official gets called away at the end of a game to handle an emergency. Having a key ensures the officials a fast exit from the court or field. Cornils remembers working one basketball game during which his partner, who had the key, made some borderline calls. After the game, he went to the scorer's table instead of proceeding directly toward the officials' locker room, further extending the referee team's exposure to a potentially hostile crowd.

Even better than giving officials their own key is escorting them off the field or court and to their locker facilities using a school security guard, a local police officer or even the home team's athletic director. "I always prefer that I'm the one who leads them if they're in my building," Cornils says. "And when I'm an official, I expect the same treatment." Another security person positioned at the door to the officials' locker room will provide an additional sense of safety and ensure that no disgruntled player, coach or fan is waiting for them inside.

(More tips on how to make your sports programs even friendlier for officials can be obtained by visiting the Officiating Development Alliance web site at www.officiating developmentalliance.org.)

All that said, precautionary procedures are not a panacea. "It's such a multifaceted problem with multifaceted solutions," says Mary Struckhoff, an assistant director with the National Federation of State High School Associations and the staff liaison to the NFHS Officials Association. "It's almost overwhelming."

"Clearly, things have changed today," Mano adds. "Referees constantly need to have their antennas up." Even though there are approximately 220,000 referees and umpires in the high school ranks, Mano says there are still shortages in many sports. Part of the reason is that many game officials aren't familiar enough with the rules of nontraditional sports. But the main reason, surveys indicate, is that officials are sick of the abuse.

To combat the problem, North Carolina is the latest state to draft legislation that would create a specific crime and punishment (likely up to a year in jail and a $2,000 fine) for assaulting a sports official. A finding of assault, under the proposal by Rep. Lyle Hanson, could be applied if the referee or umpire were injured, bumped or made to fear for his or her safety because of abuse. Currently, 16 states have protection laws for officials on the books.

Most - if not all - state associations investigate reports of confrontations between game officials and players, doling out punishments to the appropriate parties. But when the incidents involve coaches or school administrators, the state associations typically cede to individual conferences, districts or schools.

That's why, Mano says, school administrators need "speed bumps" put in place soon to curtail further incidents that lead to time-consuming investigations by school personnel, as well as damage the reputation of a school's athletic program.

But NASO will need the help of state associations and athletic directors to spread the word about its forthcoming guidelines. "It'll be very tough to say to a principal, 'You can't go here,' or 'You can't go there,' " he predicts. "But at this point, it's not an issue of control; it's an issue of moral persuasion. We need to raise administrators' consciousness. If they provide just the minimum amount of care - enough to send the signal that officials are important factors in the equation known as high school sports at their facility - we're very happy."