Recreational pool equipment that allows for flexibility can determine whether or not a facility outlasts the fads

It's every pool operator's worst nightmare. Your brand-new $10 million aquatic facility is about to open, and it's already outdated. Can this really happen?

You were part of the steering committee that created the new facility. You met with members of both the design team and the community to gather as much information and input as possible. You worked hand in hand with the design team while selecting options that would accommodate a variety of patrons' needs, from those of competitive swimmers and water-aerobics enthusiasts to families with small children and teenagers wanting fast and exciting waterslides. You also reviewed product literature, picking out features that would best serve the entire community.

Even as all this was being done, though, the aquatics industry developed new products and introduced new models - ones that may well turn out to be more fun, more durable and less expensive than what the market offered at the time you made your selections. What can an aquatics steering committee do in the face of these ever-changing products? How can you be sure that your aquatic facility will serve the needs of the community five, 10 or even 30 years from now?

To answer these questions, it helps to have a working knowledge of the history of aquatic recreation in the United States. A hundred years ago, water recreation could be found at the nearest creek or pond. Nature provided its own "water amenities" in the form of fallen logs or a river's current. A rope swing or rickety bridge brought excitement and variety, too, and almost every body of water had its own natural beach entry. When the first phase of artificial aquatic elements debuted in this country in the 1970s and '80s, the aquatic industry was essentially re-creating that old swimming hole.

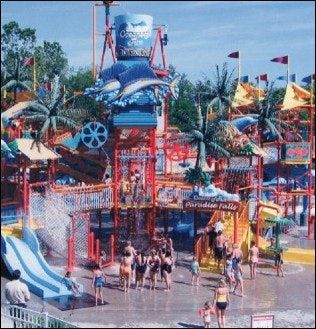

This was a time of trial and error for aquatic designers, manufacturers and operators, as they tested the recreational value of a variety of play elements and the viability of different building materials - foam, fiberglass, concrete, PVC, plastics and steel. Many of these first aquatic concepts were custom-made; each one its own creation, with unique pieces and parts. Following a particular theme or creative visual style also became popular during this period.

Creativity and customization brought its own set of hurdles, though. Often, replacement parts were not available for these aquatic play features, and when maintenance was required, the replacement part - like the original - had to be manufactured from scratch. Still, the extra effort paid off. Patrons enthusiastically responded to the transition from traditional rectangular pools to interactive aquatic facilities and water parks, as demonstrated by their repeated visits to these new recreation centers.

The second phase of the U.S. aquatics industry began in the late 1980s, as aquatic concepts, features and materials continued to evolve. Enough time had passed to allow developers to evaluate what was working and which features patrons enjoyed most. The industry responded to the growing demand by developing solutions for a variety of needs in small neighborhood pools, community aquatic centers, and destination-oriented water parks. Water recreation expanded its vocabulary with the development of water-spray grounds. In addition, more attention was given to accessibility needs, which meant that aquatic facilities could be enjoyed by all patrons, regardless of physical ability.

The custom solutions of the first phase gave way to the off-the-shelf models of the second phase. These standardized, fixed-element models brought costs down and allowed maintenance to be relatively straightforward and replacement parts to be readily available. Designers and manufacturers continued to develop better materials and finishes as selections became more focused on construction methods, life-cycle costs, durability, visual appeal and safety considerations. The industry focused on developing a "one size fits all" product concept in an effort to maximize capital dollars. What these standard models lacked, however, was flexibility. The same features appeared in aquatic facilities across the country, with nothing to set one cookie-cutter feature apart from another. Deviating from the predefined model would quickly increase costs and scheduling challenges.

The stage was set for a new, third phase of aquatic recreation development, one that would marry the hallmarks of the first two phases: fun, excitement, creativity and delivery of a quality product. This is the stage in which we now find ourselves. The goal of creating a flexible facility should take top priority in developing today's recreation facilities.

How can this be accomplished? It is often said that the only limiting factors in designing an aquatic center are imagination and budget. Concepts being explored today include the development of design elements that can be modified and adjusted easily in the future to accommodate updated concepts.

As your steering committee discusses your new aquatic center, the conversation should at some point turn to a comparison of risks and rewards. Is it the committee's preference to stay with a design that incorporates only pre-existing and proven recreation elements? Or are you willing to walk on the wild side by embracing new and different recreation elements that will separate your facility from others in the area? How important is it to your committee members to visit existing installations to see, touch and experience what you are thinking about buying?

Being one of the first facilities to offer an aquatic feature that is new to the swimming pool industry comes with a number of challenges. It will be difficult to visualize the attributes of the feature based solely on a manufacturer's renderings; it will also be tough to determine if the new feature is right for your facility without the ability to contact other facilities that already have the feature installed. Installation of the feature may be tricky and require flexibility on your part, as the manufacturer may need to make subtle changes to the feature as it is constructed. But the risks of being first can be mitigated by contracting with a reputable supplier with a strong track record of performance and professionalism. The reward will be a feature that is fresh and exciting.

By making accommodations in the design of the aquatic center, the facility can be reborn with minimal expense and disruption several times over the coming years, as new elements and operational methods are introduced. This interchangeability offers aquatic facility operators increased control, while patrons reap the benefits of an up-to-date recreation center that can meet the needs of all its guests.

In particular, this third phase meets the needs of municipalities, which have become the most common aquatics facility owners. The entrepreneurs and commercial investors of the 1970s and '80s were willing to make a shorter-term investment in an aquatic facility, with the understanding that the facility would then need to be renovated or replaced. Municipal operators, on the other hand, hold different expectations. Communities are becoming more sophisticated in aquatics programming, often running more than one aquatic center, and they expect these facilities to support the community for 20 years or longer.

Many communities have yet to experience the full possibilities of this new aquatic flexibility, however. Replacing an old feature with a new one is not uncommon, but the new selection is often limited to the infrastructure of the old element. A pump can be replaced with one that offers more horsepower, but that pipe will still be limited in the amount of water it can handle at code-mandated velocities. Selections are thus limited to those that match the size of the existing piping system and its flow rate. So while there is some room for adaptation, real flexibility cannot be achieved.

In addition, many owners wait to replace features until after they have surpassed their functional life. Meanwhile, patrons often seek out other venues that provide greater entertainment value. One way to combat this problem is to participate in a "trade-in" program with a manufacturer. Finding a manufacturer willing to swap out old equipment with a cutting-edge play feature will require some legwork. An aquatic design engineer can facilitate this process, but ultimately it is the owner who will contract with the manufacturer. Keep in mind that there will still be costs associated with installing the new feature.

You may find that your facility doesn't need the latest and greatest feature; maybe it just needs something slightly different in appearance. For example, frog slides and floating features can be recoated by the manufacturer to look like new. Likewise, installing a pre-owned feature can give your facility a much-needed boost in recreation value at a fraction of the cost of a new feature.

Another wise investment may be rough-in piping. Elements such as water sprays and waterslides may not be in the budget during the facility's planning stages, but can be added at a later time. Installed by a swimming pool contractor, rough-in piping originates from the filter room, then travels under the deck and pool to wherever the future play elements will be located. A valve box or two may also have to be installed. An electrical contractor will provide the power needs for the future pump that will operate the play elements. If you have envisioned the addition of a larger play element, such as a waterslide, structural issues must also be addressed.

Though it requires considerable forethought, rough-in piping for a future play feature can be installed for thousands of dollars during pool construction, while renovating an existing pool (by removing and replacing a portion of the pool shell and deck to accommodate pipe installation) could cost hundreds of thousands of dollars.

Individual features are now being developed with future flexibility in mind, as well. New models offer a simplified hydraulic solution that allows additional platforms to be attached to existing units. The concept is similar to a Lego or Erector set, in that its standard pieces can be taken apart, put back together or switched out to form numerous combinations. It is not yet possible for guests to carry out such active substituting and rearranging themselves during their visits, but today's facility operators are now enjoying a great deal of flexibility at relatively low cost.

A flexible feature allows interchangeable interactive components to facilitate easy relocation, replacement and upgrades. This is the first attraction that can be kept up-to-date without the cost of new equipment or modifications to the existing pool structure. Interactive railing pieces that are attached to the feature with bolts and flanges can be interchanged by a facility's in-house staff using a common wrench, a process that can be completed in a few hours, typically between the time the facility closes and reopens the next day.

Interactive elements are continually being developed, and trade-in programs are available for a small investment, allowing the feature to receive a facelift by replacing old interactive elements with new ones.

On a grander scale, play levels that radiate from a central water pipe (much like a spiral staircase) are being designed to enable rapid expansion without costly retrofitting. Each additional play platform can be added as growth and budget allow, and two or more structures may be linked to build the ultimate interactive attraction spanning any pool configuration.

Unlike the aforementioned interactive railing pieces, platform installations may take days, and it's recommended that a swimming pool contractor complete this work. If coordinated properly, however, the pool can remain open during the day while the new platform is installed after hours. With little downtime, the facility can effectively double the size of its play feature and significantly increase opportunities for interactive exploration.

As yet another option, self-contained feature systems have been developed to meet a variety of needs. A "surfing" unit, for example, is a thrill ride that can attract the young adult market to your facility from great distances. But the ride is not the only attraction. The corresponding spectator experience also contributes to the success of these types of demographically targeted elements.

Meanwhile, today's sophisticated mechanical systems are allowing the same pools to serve wide-ranging audiences. The water temperature of an indoor water slide catch pool can be adjusted quickly to meet the needs of the therapy market, for instance. After the therapy session has concluded, the pool returns to a water slide splashdown at the flip of a switch.

The programming stage of the aquatic facility is the time to think big. Being creative during this time will allow you to develop a facility that can outlast the latest fads and adapt to future developments. Decide on the play features your dream facility should have, and then hypothetically place them in your pool's design.

Once all flexibility options have been weighed, the question becomes, "How often should your pool flex?" Change as infrequent as once a year may generate excitement, especially when it takes place midseason. A change made in the off-season may get little notice, but one made during the season can certainly create a buzz around your pool, as patrons anticipate this year's new feature. The more you flex your facility, the more visitors you can expect to explore and enjoy the new elements.

As the aquatics industry gazes into the future, it sees more changes on the horizon. But whatever the next phase brings, your facility can adapt if you plan ahead. Do your homework. Determine what is important to your community, then maximize flexibility through creativity. Facility development is high-level adult play. Have fun creating and implementing a vision that is perfect for your new aquatic center and the community it serves - now and 30 years from now.

Doug Cook ([email protected]) is design studio director and D. Scot Hunsaker ([email protected]) is president of Counsilman/Hunsaker & Associates, 10733 Sunset Office Drive, Suite 400, St. Louis, MO, 63127, 314/894-1245.