His fee for such on-call services? Nothing but a bird's-eye view of his beloved Buckeyes. "It's definitely worth the drive to be able to take in an OSU football game, see my friends from the staff and contribute to the gameday atmosphere at Ohio Stadium," says Aukeman, a software engineer in the metropolitan Washington, D.C., area.

Armed in November 2001 with only conceptual knowledge of how animation worked, Aukeman joined OSU's scoreboard staff - one of just a handful of collegiate scoreboard staffs nationwide composed primarily of students. Like his undergraduate coworkers, Aukeman was paid an hourly wage for time spent creating scoreboard animations in his free time, as well as preparing and running the scoreboards on game days. But money was never the motivator. "For me, it was very much a privilege to be a part of Ohio State athletics, even if the role I played was rather peripheral," he says.

That type of team spirit is not uncommon among scoreboard staffers at every level of sport. And that's a good thing, because in many cases the men and women sitting at computer keyboards and standing behind replay cameras in today's state-of-the-art athletic facilities actually outnumber the players on the field. Some make a career out of freelance scoreboard work, bouncing from one booth to another as the sports seasons change. Others moonlight at night games while holding down day jobs. All are counted on to help create a stadium experience that transcends sport itself.

"We understand that it's more than just a game," says Russ Jenisch, director of scoreboard operations for the Cincinnati Reds. "The Reds are going to win some games and they're going to lose some games. Regardless, we want fans to leave with a smile on their face, saying, 'I got my money's worth because I was entertained.' That's our goal."

That's not to say that reaching such a goal doesn't present its share of staffing challenges. The mix of commitment and experience among workers, not to mention the wide range of skills required to complete today's myriad scoreboard tasks, make filling out the game-day lineup daunting for some directors of scoreboard production crews. "I turn over a lot of rocks," says Jenisch, who himself pulls double duty as an associate professor of communications at Northern Kentucky University. "It isn't the same 21 people every game, and that's what makes it difficult."

According to Brandon Verzal, video producer for the Seattle Mariners, the average Major League Baseball scoreboard crew numbers 15 workers, with a range of 10 to 22. Based on survey input from 15 MLB teams, Verzal identified 21 distinct game-day production responsibilities (though actual job titles may vary from team to team). Of those positions identified in the survey results (released by Verzal in November), only three - technical director, audio mixer and video quality controller - are filled full time for one or more teams. The most common positions (identified by 11 or more teams) include technical director, graphics specialist, replay operator, audio mixer, camera operator and main matrix board operator. The least common positions (identified by three or fewer teams) include assistant audio mixer, assistant matrix board operator, out-of-town scoreboard operator, signage operator, closed-captioning provider and organist.

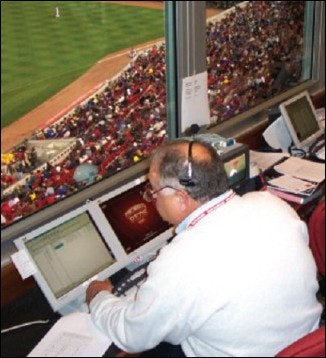

In their role, directors of scoreboard operations are in near-constant headset communication with everyone imaginable, from the video engineer seated behind a bank of monitors to the public address announcer seated behind a solitary microphone. "It's organized chaos, and I sometimes feel like a traffic cop," says Jenisch, one of three individuals contracted by the Reds full time to coincide with the opening of Great American Ball Park last year. "It's really a multitasking skill, because you're listening, you're looking, you're talking. You might be listening to one thing, looking at another and saying a third."

Stroll through Great American Ball Park and you'll find eight scoreboards: a monochrome matrix board, a full-color video board, two 230-foot-long ribbon boards, a scoreboard that chronicles other league games, a scoreboard that monitors pitch speed, and two circular LED boards that serve as the paddlewheels on a steamboat "home run" feature - not to mention rotational and static sponsorship signage.

Peek inside the park's scoreboard control room (actually two rooms located along the first-base line that are adjoined by sliding glass doors) and you'll find Jenisch, the director; two individuals who update balls, strikes, outs, lineup changes and promotional information on the main matrix board; one person who controls graphics on the ribbon and "home run" boards; another playing sound effects and situational graphics (after a strikeout, for instance); another who mixes the audio from the PA system, organ and canned music sources; another who prepares text messages (such as "Ken Griffey Jr., 1 for 3, single, RBI") to superimpose over live video; another who keeps a scorebook to ensure such text messages are statistically accurate; a video switcher who executes the commands of the director; a video engineer who monitors camera feeds for consistent color and brightness; two replay operators (one using videotape, the other a computer server); and one technician who ensures that all broadcast signals are being transmitted properly. Outside the booth are five camera operators, including one "rover," who uses a wireless camera for close-ups of such scattered events as performers singing the "Star Spangled Banner" and fans participating in between-inning promotions, as well as a grip, who accompanies the rover and points the wireless camera's antennae toward a signal receiver. Rounding out the game-day roster is an audio assistant responsible for running microphones to destinations on the field and in the stands as situations dictate.

All of these individuals work from a master script that breaks down what is to happen (from a paid-sponsorship perspective) on each of the scoreboards and when. At both the professional and college levels, scripts are usually compiled days in advance by someone in the marketing department, who has the ear of the director throughout a game in the event the script needs to be changed. It may be as simple as shifting a scoreboard advertising spot to a later timeout in order to allow the band to boost fan spirits during a critical point in a particular game.

Larry Rosen, senior director of broadcasting and production for the Baltimore Ravens, even fields the occasional traffic alert from parking attendants before posting it on the matrix board at Ravens Stadium. "If it's shared electronically with our audience, it all comes through me," says Rosen, who employs 25 to 30 individuals - from runners to statisticians - for his game-day production. And unlike baseball, with its near day-to-day schedule of games, football's game-a-week pace allows the Ravens' scoreboard staffers sufficient time on weekdays to produce coaches' shows for television and special video features for Sunday's scoreboard show.

It's enough to keep five full-time Ravens staffers - a producer, an editor, a camera operator, a production assistant and an engineer - busy every single day from Aug. 1 until season's end, according to Rosen, who - somewhat surprisingly, perhaps, under such conditions - experiences little staff turnover. "Everybody wants to work our show," he says confidently. "It's unilaterally seen as a great show and a lot of fun."

The Ravens boast one of the largest full-time scoreboard staffs in professional sports, but unlike years ago, most pro teams now employ at least one or two full-time scoreboard specialists. That's not so much a reflection of the growing sophistication of today's scoreboards and their prominence in modern facilities as it is an organization's desire to enhance production possibilities, according to Verzal. "Teams had previously been contracting with a production company to come in and run the show," he says. "They didn't have as much creative control that way. If they wanted to do special videos for a special night, they'd have to contract with that company again to do something above and beyond what was outlined in the initial contract."

Most of the 16 staffers on hand for each Mariners home game carry five to 10 years of experience with the franchise, and many can be counted on to work 70 or more games a season. That's rare among MLB teams, Verzal says. In the odd event that he needs a temporary stand-in, it's usually someone from outside the organization recommended by a current staff member. "If we post something in the paper, we get 500 applicants, most of whom say they have edited something at home," Verzal adds. "That's fine, but it takes a lot longer to train them, and we have to kind of throw them into the fire here."

Jenisch keeps a call list of some 80 part-timers and freelancers to ensure his bases are covered from game to game. "If I had the same crew every game my job would be a lot easier," he says. "Because of the types of people I sometimes get, I'm forced to spend a lot of time instructing them. We had one person - a retired teacher - who worked our ribbon boards every game last season, and three or four people who worked 75 or more of the 81 home games, but I've got to fill in the other 15 positions. My biggest task every week is to make sure we have the positions covered with competent people for every game."

His Northern Kentucky connections help Jenisch, who teaches television production, fill up to five college internships for the Reds each season, and those who prove themselves competent are offered regular positions on the scoreboard crew the following season.

Scoreboard operations that rely almost exclusively on students face staffing challenges all their own. "They do a great job, but the hard part is constantly training them, because they graduate and move on," says Cecil Harrison, video supervisor for special projects at Brigham Young University. "It's not the kind of situation where you get your group together and you're all comfortable, because every two or three years you get a whole new set of people."

Particularly high attrition rates last fall at Ohio State prompted the rescue calls to Aukeman, who recalls a rigorous screening process from his days as an undergraduate computer science and engineering major and aspiring scoreboard staffer. "It's an all-day event that takes place in the stadium press box," he says. "In addition to having to face the entire dozen members of the staff in an interview, there is a written personality test and quite a bit of drawing. I was particularly surprised when they told me to make a 15- to 20-frame animation in an hour. It's all very intimidating."

Harrison draws BYU students from the usual departments - communications, film, media arts - but area of study is not necessarily the best indicator of who will best serve the scoreboard staff. "Interestingly enough, we've found the most important thing is whether or not they like sports," he says. Adds Aukeman, "The students who apply to work for the staff are not only highly motivated and talented, but they're often rabid Ohio State fans, as well. They want to represent the university and the team as well as possible through their work."

That may be, but the "exuberance of youth," as Harrison points out, can sometimes cloud programming judgment. This past season, Harrison vetoed a student's suggestion to display on the football scoreboard a camera shot of opposing fans with bags over their heads posing as a BYU rooting section. Aukeman had one of his football animations pulled from Ohio State's rotation following the 2002 home opener, because an associate athletic director deemed it too political. Titled "Strategery," the screen depicted George W. Bush with a thought bubble filled with X's and O's - a tribute to comedian Will Farrell's impersonation on "Saturday Night Live."

For its part, the NCAA currently has no guidelines regarding appropriate scoreboard programming, though existing NCAA bylaws may indirectly involve scoreboard use. According to the May 7, 1999, NCAA Register, a Division I institution sent a letter of reprimand to its scoreboard staff for displaying a "Welcome Recruits" message four times during a home football game, a violation of NCAA recruiting rules. "We're more or less self-policing at this point," Harrison says, adding that individual athletic conferences often create their own scoreboard guidelines, usually pertaining to the use of controversial replays and the fair treatment of opposing teams (no band or canned music once a team breaks its huddle, for example). "We've tried to err on the side of caution, because the last thing we want is for the NCAA to come in and tell us what we can and cannot do."

The creative aspects of scoreboard show production make the work seem, well, less like work. "It's quite satisfying to have your work displayed on a 30-foot-high screen in front of 100,000 fans during a football game," says Aukeman, who admits he and his OSU crewmates could have found higher paying campus jobs. "Even so, there is no lack of bright and talented people who love this job and take it very seriously."

Not surprisingly, the professional level is no different. "We run my control room like a network-level telecast that is being beamed to the 70,000 fans in the stadium," says Rosen. "We want to motivate fans to come to the stadium, and one of the ways we do that is by providing a network-level broadcast in addition to all the other experiences that you can only get at the stadium."

Verzal, who credits his years on the University of Nebraska's HuskerVision staff for helping him land a job with the Kansas City Royals upon graduation in 2000, found that the average amount paid per game to freelance scoreboard staff working for the 15 MLB teams that participated in his survey was $1,870, with a range of $828 to $2,831. "There are people who can make a pretty good living doing this," says Jenisch, who paid freelancers just under $200,000 total in 2003.

Verzal based his figures on a six-hour workday, since some teams pay by the game and others by the hour. Jenisch, who worked for the Reds part-time prior to last season, can only dream of penciling six-hour workdays onto his summertime schedule. "Before the Reds made the full-time commitment, I'd get to the stadium about four hours ahead of time. Now our full-time people are in at 9 a.m. preparing for a 7 p.m. game. During the season, 14-hour days are not unusual," he says.

"You can't even look at it as a long day," says Rosen of the time commitment expected of the Ravens' full-timers. "There's a finite amount of material that needs to be produced, and you just do it until it's done." For that reason, Rosen believes pay should come by the project, not the hour. "Basically, my sense is that if you use hourly rates you're motivating people to work slowly, and we have no time to work slowly," he says.

Time spent working on a scoreboard staff has certainly helped put some individuals on the fast track. Verzal says his former coworkers at Nebraska, which is widely regarded as a hotbed of video production talent, have landed with the Tampa Bay Devil Rays, the Houston Rockets, the U.S. Olympic Committee, ESPN and ABC's "20/20." Adds Jenisch, who lost a staffer to ESPN's "Sunday Night Baseball" among a half-dozen recent defections, "The people at Fox Sports Net and ESPN are doing the same thing I'm doing - trying to staff a game with 25 or 30 competent, qualified people. They'll steal them from me, and that's OK. That's what I want to have happen, especially for those who were once my students. I don't want them to spend their life working a part-time job at a television station and working part-time at Reds games. I want them to move up and succeed, and that's what happens."