From pedestrian plazas to shrubs and shade trees, the ground surrounding a a sports venue play an important role in selling spectators and participants on the overall game-day experience

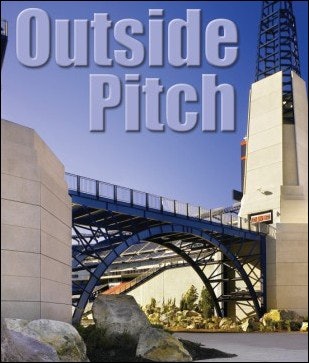

An 80-foot-tall lighthouse summons visitors to Gillette Stadium in Foxboro, Mass., and a steel footbridge further guides them toward the gates (left). Boulders stacked to resemble an ocean break wall pay homage to the region's maritime heritage, as do native sea grasses, birch trees and blueberry bushes. It's a scene that begs attention, if not a raised eyebrow or two. Boston Globe columnist Robert Campbell, describing his first impressions only weeks before the stadium's official opening in September 2002, wrote, "Gillette is basically a huge, powerful pile of steel and concrete that happens to be wearing a small tutu of coastal New England motifs. If any remnant of the natural world still existed on this site, it's now gone, replaced mostly by vast asphalt parking lots. In compensation, the architect offers us, with his rocks and grasses, a kind of stage-set version of nature. It's pure cosmetics."

If brick-and-mortar sports venues are the meat and potatoes of their project-site platters, then landscaping represents the parsley garnish. It's the rose-petal frosting that borders the birthday cake. Make no mistake, whether the goal is to turn outdoor sports complexes into park-like settings or lend human scale to Herculean stadiums, landscaping plays an important role in selling spectators and participants on the overall game-day experience. Even Campbell recognizes the challenge facing athletics facility landscapers, admitting that Gillette's exterior imagery "all adds up, surprisingly, to a less pretentious, more humane place than most stadiums, and a pretty good place to watch a game."

"Owners want to create a good image for their buildings and surrounding spaces, because marketing is part of the end goal - to attract people to these facilities," says Bill Inman, vice president of Hitchcock Design Group, a Naperville, Ill.-based landscape architecture firm specializing in recreation facilities. "You want people to say, 'Wow! This really looks nice.' "

The wow factor finds its roots in the early planning stages, when three-dimensional modeling lets facility owners visualize what is possible for their building's landscape. "Some clients don't understand the three-dimensional nature of land," says Mark Dawson, a landscape architect with Sasaki Associates in Watertown, Mass. "It's always wonderful to take one of these foam models into a meeting and watch people's eyes get wide when they say, 'Wow! We didn't know we had those kinds of conditions - or we didn't appreciate them.' "

But clients will have to appreciate much more than that regarding their new surroundings. According to Inman, factors that greatly influence landscape design include the facility owner's ability to maintain the landscape, the look that the owner wants, the time frame in which the owner wants to see the desired look and the overall style cues provided by the facility itself.

Maintenance tops the list for good reason, and an owner's commitment of manpower and resources to keeping up the site's appearance long after the landscape contractors have left is a critical consideration. "We've seen some projects that have ultimately gone into decline because of a lack of maintenance," Inman says. "We are very careful to fully understand what clients' capabilities are, because we want to provide something for them that they can sustain."

Engaging maintenance staff in planning sessions is one way to avoid design mistakes, according to Erik Sweet, of Seattle-based landscape architecture firm Cascade Design Collaborative. Simple answers to questions regarding mowing and pruning - whether the manpower, equipment or desire exists to do much of either - can greatly influence initial design decisions. "A lot of the guys will tell me, 'Look, I've got lots of lawnmowers. I've got a 60-inch riding deck. Give me some trees with a 4-foot circle of mulch around them, and I can mow the rest.' That can actually create a very nice landscape," Sweet says. "If you know they're going to manicure the lawn, you can do some nice things with berms to create subtle changes in topography."

"I do believe that the simplicity of design is art itself," adds Dawson. "You can do a really great design that is poorly maintained or can't be maintained and it will look really bad soon. You can do a very simple design that's well maintained and it will look stunning for a long time. I think a lot of times things can get overdone."

That is not to say that a design can't be underdone. While many of the principles that apply to landscaping a residential yard translate to commercial settings, the unique challenge to landscaping sports facilities is their sheer size. A football stadium's massive height and footprint will overwhelm perennial beds better suited to a strip mall. "Sports facilities are big and imposing in their scale, and require a well-thought-out landscape design to help bring these hulking, muscular things back down to a human scale," says landscape architect Brian Smith, a senior associate at HOK Sport+Venue+Event in Kansas City, Mo. "You want to think about including some mature ornamental or canopy shade trees that look like they've been there awhile."

Exterior appearance takes on greater importance if tailgating is a tradition among fans of a stadium's primary tenants. "They spend as much or more time outside the stadium as they do in, so it's important that some sensitive thought be given to how the exterior environment presents itself," says Smith. Some exterior stadium components, such as service docks and parking bays for broadcast trucks, beg to be screened behind rows of trees or shrubs. "We use plant material creatively to make those things sort of go away, so the fan shows up and doesn't spend too much time pondering the loading dock," Smith says. "Ideally, he or she doesn't even know it's there."

With ever-increasing attention paid to fans' overall game-day experience, landscape architects agree that the impact of site design should begin while visitors are still in their cars. "Whether it's a soccer, football or baseball stadium, you need to provide a site context that really has a sense of entrance about it and a clear organization of movement through the site," says landscape architect Rich Gardner, a principal at RDG Sports in Des Moines, Iowa. "We certainly would hate to see a facility built with just a parking lot and no clear visual announcement that begins to build excitement."

Like the structures they serve, stadium parking lots can be overwhelming in size. According to Smith, any effective landscape design places utmost importance on patron wayfinding. "In a big ocean of asphalt - say, at an NFL stadium - people have to figure out how to get to that building over there without getting run over by a bus, and we'll use plant material to help those people find sidewalks," he says. "They might see a row of trees off in the distance and realize, 'Hey, that's a pedestrian circulation route over there. If I can just get over there without getting killed, I've got a good chance of getting into the stadium.' "

The bigger the parking lot, the greater the need for an effective storm-water strategy - another critical landscape consideration. Traditional means of managing runoff from impervious surfaces has been to pitch the pavement in the direction of pipes that channel rainwater toward on-site retention ponds. Increasingly, however, landscape architects are striving for low-impact site designs, including parking lots that put rainwater to use without sacrificing the valuable real estate consumed by storm-water basins. One technique is to substitute curbing with car stops that allow water to flow into oversized landscaping islands, located every 10 parking spaces or so. "You're now using the soil as a means to remove the fine particulates or heavy metals that come out of motor oils, radiator fluids or brake dust," Sweet says. "A lot of plants will use the heavy minerals in those byproducts; we give them micronutrients anyway when we fertilize."

Another, more extreme low-impact approach is to avoid using pavement anywhere in the parking lot except access lanes. Cars instead are parked directly on grass areas (which can be stabilized just below the surface with sheets of plastic honeycomb material), allowing for widespread percolation of rainwater. "We try to let it filter into the site, perhaps even to the point where no water actually leaves the property ever - even after rainfalls," Inman says. "That's a trend that's gaining a foothold in the industry."

Walkways and plazas likewise can be tweaked to better handle rain. Concrete pavers not only provide the landscape architect with design options in terms of size, color and layout, they also curtail runoff by allowing water to permeate the sand-filled cracks where one brick abuts another.

However, materials selection for pedestrian traffic areas more often is based on initial cost. Asphalt is the least expensive material and highly discouraged from an aesthetic standpoint. Poured concrete is popular and typically priced at $4 to $5 a square foot (stained and/or stamped concrete will cost slightly more). By comparison, concrete paver may run $7 to $8 a square foot, with granite and other varieties of natural stone costing $10 to $12 a square foot. Some designers put great stock in pavement selection (Gardner, for example, points out that glare off concrete may adversely affect visitor comfort), but Dawson thinks that facility owners, particularly colleges and universities, can spend their money more wisely in other ways. "I would rather spend it on lighting than on brick paving," Dawson says, pointing out another key component of the outdoor landscape. "I find a well-lighted project to be personally rewarding, because people feel safer and they better understand the site's hierarchy of movement."

Number of fixtures and quality of illumination are certainly factors to consider when selecting appropriate lighting, but so is style, and outdoor lighting manufacturers offer a broad spectrum of options - from traditional acorn-shaped lanterns to cutting edge designs. "We've worked on a lot of modern-themed stadiums where we've tried to do very elaborate and cool light fixtures everywhere, and those items can run the gamut of costs, just like pavement," Smith says.

Landscape architects often specify outdoor lighting that directly matches what has been chosen for the building itself. "You want to make sure that all of the site and building components look like they are of one thought process," says Inman, adding that this concept of seamlessness applies to plantings, as well. "Plantings certainly can be part of that. Are they formal? Informal? Symmetrical? Asymmetrical? If you have an entrance to a building that is very symmetrical, a formal planting outside would be a direct reflection of the building's architectural style. You might have low, highly manicured hedges along with a very neat and tame application of perennials and ornamental trees. But if you have a prairie style building, one founded on the principles of Frank Lloyd Wright, and tried to nestle that building into the landscape so it looks like it's coming out of the landscape, you would include very broad, sweeping beds of ornamental grasses and perhaps native trees that might look a little floppy."

In the case of a collegiate arena or student recreation center that enjoys a tangential relationship to a main campus corridor, a complementary nod should be given not only to the building in question, but to the surrounding grounds, as well. Selecting similar if not identical plantings and hardscape elements can help to preserve a campus's timeless quality. "You don't want to build the Bellagio fountain," Dawson says. "You don't want it to be so unrelated to the campus that it will be a white elephant in 20 years."

Though only one facet of landscape architecture, plantings are often what one equates with the discipline. As previously mentioned, visual screening, wayfinding and water treatment can be important functions of a site's chosen flora, but trees in particular can also serve as sun and wind blocks along sports fields, provide shade to plazas and spectator seating, and even add a splash of school color to the game-day atmosphere. Still, one must take care in deciding what species are up to the given task.

As a rule of thumb, trees native to a specific region not only look like they belong but will exhibit the lowest transplant mortality rates and longest lifespan in the face of extreme climate demands - from freeze-thaw cycles to precipitation amounts. "If we bring in an ornamental landscape species from somewhere where it gets a lot more rain, I now have to irrigate more, which drives up my maintenance costs," Sweet says.

Homeowners tend to avoid what are commonly called "dirty" trees - honey locusts, willows and the like - that drop extremely small, hard-to-rake leaves. Maintenance staff, on the other hand, may actually prefer small-leafed trees in the hope that the leaves blow away in the wind or at least don't clog storm drains, as might leaves from a maple. "Dirty trees to me are trees that will drip sap and make your walkways or plaza spaces sticky," says Sweet, who also recommends fruitless varieties of pear, crabapple and other flowering trees for landscape applications. Fruit and berries dropped from trees can stain pavement, and provide visiting children with something to throw or, worse, swallow. The choking risk presented by small fruits and the potential toxicity of berries mustn't be ignored, Sweet says.

To facility owners looking to incorporate trees within their landscape, size often matters, and certain species grow faster than others. Sweet offers this caveat: "A lot of the fast-growing species have very soft wood, and therefore can become more susceptible to pest problems or limb loss when they get larger. They can also outgrow their root structure and become top-heavy. It might not be a problem for 30 years, but what happens if you lose one-third of those trees that you've planted in your attempt to keep a row. Now you have to go back and replant, and you don't have the consistency of size."

Facility owners should also protect themselves against transplant mortality by demanding at least a one year blanket warranty on all plantings. The landscape architect, landscape contractor and facility owner should then walk the property 60 days in advance of the warranty's expiration to determine if any replacements are required. Sweet suggests going a step further - making it a prerequisite of the bidding process that the landscape contractor employ its own maintenance division, and requiring each bidder to assign a maintenance cost to what Sweet calls a "plant establishment period" of two years, during which the contractor will handle all irrigation, fertilization, pruning and winterization. Only after successful completion of the plant establishment period will the contractor be awarded the specified retainer, which may amount to tens of thousands of dollars. "We've seen that if landscape contractors know they're going to be responsible for maintenance for two years, they tend to follow industry standards a little better during the installation process - ensuring that, for example, they've got the root balls done right with the right amount of soil around them," Sweet says.

As a percentage of the entire facility budget package, landscaping too often receives short shrift from facility owners, some landscape architects contend. "We draw about 10 times as much of it as we know we'll really get," says Smith. "But you won't get it if you don't ask."

Dawson's firm has identified a workable budgetary scale that suggests construction projects totaling up to $15 million should allocate 15 to 20 percent for site development, including plantings, pedestrian traffic areas and lighting (though a landscape design may also incorporate such elements as flagpoles, fountains, walking trails, seating, statuary, even relics unearthed during excavation). For project budgets exceeding $15 million, the landscape percentage begins to drop into the 10 to 15 percent range.

One thing facility owners should keep in mind is that landscaping, even lighting, can be installed in phases - an approach that may allow future monies to be tapped from alternative sources, such as a college or university's physical plant department. Moreover, landscape architecture - providing it's properly designed, installed and maintained - only improves with age. "The beauty of landscape architecture is you can phase it in over time and you can always buy smaller material," Dawson says. "I'm never afraid to tell a client, 'If you can't afford a 6-inch-diameter tree, buy three two-inch trees instead for a fraction of the cost. In five years, you'll have a pretty attractive property and in 10 years it will be stunning."

To an even greater degree than today's athletic facilities themselves, surrounding landscapes are stretching the limits of imagination. "Landscape architecture is a wonderful discipline, and the reason is you can't put any project in a quote-unquote box," says Inman. "Every design is custom."