Separating recyclables from game-day trash saves athletic departments money at the landfill and helps communities in immeasurable ways.

Game-day cleanup hasn't changed a great deal over the years, but the process is becoming more labor intensive as pro teams, college athletic departments and other spectator venue operators grapple with the mountains of bottles, cans and cups that until very recently headed to the landfill with hardly a second thought. They're finding the necessary adjustments include the purchase of specialized equipment, the hiring of more hands and partnerships with various organizations - but they're not complaining.

"The process is more complicated," notes Bob Beals, assistant athletic director for operations and events at the University of Oregon, "but people are doing it for the right reasons."

Recycling programs are by now well established in most communities, whether in cities and towns, or on university and college campuses. The stadium, though, is a different animal. Many athletic departments have no recycling program beyond the gathering, separation and baling of paper and cardboard culled from concessions stands. With much of the potential recyclable material coming from parking lots and other adjacent sites, stadium operators have left the deposit-bottle pickup to area homeless people - Erwin Sanvictores, director of recycling for the Urban Corps of San Diego County, which handles cleanup at Qualcomm Stadium, calls them "independent uncertified collectors" - and dumped the rest.

This is a characterization that rankles those who are doing their part. As Beals, whose department has been stung by some locally published criticism, puts it, "We do recycling, and we don't get credit for what we do; we're not perfect in some people's eyes. As much as we want to be a perfectly green event, we're not."

Yet, it is a fact that the culture of major sporting events - football games in particular - is a world away from the gradually greening culture at large. "Tailgating is what drives a lot of our issues," says Beals, who must dispatch trash-collecting volunteers to parking lots before kickoff in order to avoid being buried. "With sporting events held in arenas, there isn't that same mentality. And outside, the football mind-set just can't be duplicated at a concert or baseball game."

Adds Barbara Angeletti, recycling coordinator at West Virginia University, "I'm always amazed at the number of people who come to town on football Saturdays who never make it in to the game. We have recycling bins inside the stadium, but the bulk of the material - 90 percent of it is aluminum cans, and 90 percent of the cans are Bud Light - comes from tailgaters in the surrounding parking lots."

Athletic departments are now giving more attention to these outlying areas, placing bins there and using volunteers throughout game days to make sure the bins don't overflow. The most visible evidence of WVU's recycling program, a collaborative effort between the university, the West Virginia Department of Environmental Protection, the Montgomery Regional Solid Waste Authority and Coca-Cola, is the 219 gold-painted bins placed around the stadium (and, subsequently, residence halls, the basketball arena and other locales). In what might seem like overkill, Angeletti's department now gives large plastic bags to hard-partying tailgaters in which to deposit recyclables - all part of the effort to encourage fans to get with the program.

"The bins are clearly marked, 'Mountaineers Recycle,' " she says. "We also do PSAs and radio ads, put information out to all the students, use e-news to let faculty and staff know about it. Plus, the athletic department sends a flyer with recycling information to people who buy season tickets."

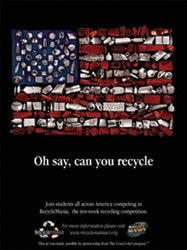

But UC Berkeley is far from alone; if more universities had successful programs in place there'd be no need for RecycleMania. The brainchild of Ed Newman (Ohio University Campus Recycling) and Stacy Edmonds Wheeler (Miami University Campus Recycling), RecycleMania began in February 2001 as a competition between the two schools to see which could recycle the most over a 10-week period. Six years later, 201 colleges and universities are involved, competing in different contests to see which institution can have the highest recycling rate or can collect the largest amount of recyclables per capita, the largest amount of total recyclables, or the least amount of trash per capita. Since 2004, RecycleMania has partnered with the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency's WasteWise program, and that year it received the National Recycling Coalition's Outstanding Recycling Innovation Award.

The EPA's Beth Koprowski says that smaller campus subsets can take part in the contest, and there has been talk among the WasteWise and RecycleMania staffs that perhaps the competition should be split into divisions as a way of comparing campuses to campuses, dining halls to dining halls and arenas to arenas, for example. For now, though, sports facilities are somewhat peripheral to the contest in spite of the amount of recyclables they produce.

That said, the RecycleMania web site does acknowledge the effectiveness of sporting events in publicizing the contest and raising awareness of the need to recycle. One suggested RecycleMania event is "Adopt-a-Game," in which two teams of volunteers wearing promotional T-shirts re-create the campus-wide contest by picking up recyclables throughout the seating bowl and concourse during the course of actual sporting events.

Having run such an event at Ohio University basketball games for several years, Newman can attest to its effectiveness. In terms of raising awareness, he says, nothing beats actively involving spectators with trash pickup. Beyond that, there's the "yuck" factor.

"The stuff that comes out of basketball games, if it gets mixed together you almost don't want to mess with it," Newman says. "When you have people collecting trash as it's generated, they can keep the drinks from the spittoons from the nacho cheese-covered stuff. It makes a big difference in terms of the amount of recyclables you can recover."

In the meantime, though, the post-game cleanup continues as before, with a few adjustments. The Oregon athletic department uses approximately 10 different community and volunteer groups, which it dispatches to separate areas of the facility: Ramps, seating bowl, public rest rooms, perimeter concourse, parking lots, suites. (Beals says this is an improvement over the old system, in which each of the groups did the whole stadium for one particular game - a daunting task.) Volunteers sweep all the garbage from the rows to the aisles, and sort out recyclables there before the trash gets pushed down to field level. Oregon made one major improvement to its trash-collection process six years ago when, as part of the renovation and expansion of Autzen Stadium, the athletic department purchased an on-site compactor. The method for gathering recyclables, however, is still hunt and peck.

Athletic department, or sanitation department? It's getting harder to tell the difference.

Says Christensen regarding the OSU athletic department's purchase of the mini-MRF and compactor, "They have more money than we do. And this way, they show everybody their commitment to sustainability."

Beals says Oregon is hoping to develop a Master Recycler program with the city of Eugene, similar to the Master Gardener concept. The program's main purpose would be to deal with game day's biggest surge of empties: Right before kickoff, as fans enter the stadium in a rush, draining their last containers of soda, beer or liquor as they approach the gate. "We're going to work with the city to develop a plan where we can steer fans to containers and clearly separate redeemables, recyclables and trash right at the outset," Beals says.

OSU Campus Recycling, meanwhile, is hoping to convince the athletic department to spring for a baler, something that for a mere $22,000 investment can package up crushed plastic bottles into more manageable units.

"Recycling is something that we're building on every year," Christensen says. "We really feel we haven't gotten that far yet. As it stands now, we don't have the folks or the funding to do everything we want to do. So we're doing it in steps."

In fact, those who have committed to recycling are doing quite a bit, even if it's hard to find anyone who believes they're doing enough. The University of Oregon athletic department, for example, recycled 18 percent of the bulk it collected last year, a sizable amount considering it was all accomplished without the aid of machinery. The Rose Bowl's recycling program just celebrated its fifth year by taking in eight tons of recyclables - an estimated 70 percent of the recyclable waste generated on the day of the game. The "Green Forum" initiative put in place by Palace Sports & Entertainment Inc. at the St. Pete Times Forum, home of the NHL's Tampa Bay Lightning, is annually recycling 24,000 pounds of beverage containers, equal to 600,000 plastic bottles and aluminum cans. Last year's seven West Virginia home football games, meanwhile, attracted 411,000 spectators and netted 19,000 pounds of recycled plastic, aluminum and cardboard. "That doesn't sound like a lot," Angeletti says, "but when you consider what an empty plastic bottle weighs, that's an awful lot of stuff."

The market for recyclables is not extraordinarily lucrative, which is the most common excuse offered by sports organizations that don't recycle. It's a shortsighted attitude, recycling proponents say, given the many ways in which people benefit. Consider the Urban Corps of San Diego County, which recycled about 25 percent of what it picked up after San Diego State University Aztecs and San Diego Chargers games last year - about 66 tons of material. Whether its garbage hauling costs are based on weight or volume, the city clearly benefited by lower tipping charges at the landfill; at-risk youths who the Urban Corps hired to pick up trash got a paying job out of it; and the Urban Corps used money it received from clients such as Qualcomm and sales of secondary materials to subsidize its charitable program.

Beals believes the preoccupation with dollars is beside the point. "We're not trying to make money; we're after a wash, so to speak," he says. "That said, while we don't have the numbers, we're convinced that we have saved money by recycling. Intuitively, the number of trips to the landfill has been reduced, so we're saving money on that end."

In Morgantown, W.Va., $2,100 brought in through the 2006 sale of recyclable material - mostly aluminum cans, which are currently fetching an all-time-high price - was presented at the spring football game to West Virginia University Children's Hospital. "It isn't a fortune, but it's something that previously had been put in the trash," says Angeletti. "We feel really good about that."