This article originally appeared in the January 1986 issue of AB with the title, “Spectator Seating: Get Them into the Stadium and out of the Living Room.”

Old timers say a winning team will fill any stadium, regardless of the comfort, or lack of it, experienced by the spectators. There’s evidence to support this claim, but the growing menu of sports programming on television, which can be viewed in the comfort of one’s living room, is a constant threat to stadium attendance.

Today’s fan demands a clear view of the playing field, a comfortable seat and climate control, in addition to a winning team. The domed stadium is a clear response to that spectator. Perhaps we are getting soft, but this demand for creature comforts is bound to grow in the years to come, particularly as sports promoters try to attract more women to these events.

Designers and builders of sports facilities of the future will be challenged to provide spectators with seats worth paying for and a location that will make them forsake the advantages of their living room recliners.

There Must Be Trade-Offs

The problem for stadium seat designers is that the greater the degree of comfort for the spectator, the higher the cost of the facility. The greater the facility cost, the higher the price for admission. As in most aspects of life, there must be trade-offs.

The same is true for seating arrangements. Most spectators want to be as close as possible to the action—along the 50-yard line in football, home plate and the pitcher’s mound in baseball. It’s the goal of good stadium design to place as many spectators as possible close to and facing this center of action.

The stadium seat deck consists of a system of stepped platforms called tread and risers, which form the basis for structuring spectator seating into a good viewing position with proper sight lines.

For the purpose of design, let’s assume that an average person measures 4 feet even from floor to eye level when seated, and 3 inches or more from eye to top of head.

The best layout occurs when the spectator can see between the heads in the row in front of him with a focal point on the ground at the edge of the playing field.

To plot the upward curve of the seat deck, we assume that a spectator’s line-of-sight will originate form a point 4 feet above his tread and pass through a point 4.25 feet above the treat of the corresponding seat row in front of him. Plotting each row in this manner produces parabolic curves of increasing steepness.

To provide an ideal seating location for all spectators of a hypothetical, 50,000-capacity football stadium, one would have to design two single-file rows of seats with 25,000 on each side of the 50-yard line, each extending to a height of 9 ½ miles. Hence, the need for compromise.

Multiple Decks a Partial Answer

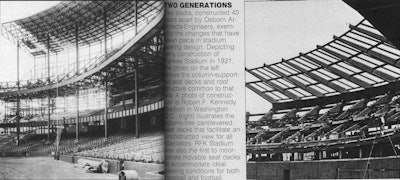

The number of seat decks currently utilized in stadia range from one to as many as seven. Yankee Stadium was the first major stadium in this country to be designed (in 1921) with more than two decks, primarily because of site restrictions. The modern Astrodome, with its seven seat decks, had to contend with minimizing roof spans and maximizing internal space.

The University of Michigan and the Yale Bowl are representative examples of stadia that have poured concrete seat decks cast directly on the ground, a means for achieving construction economy.

As a general rule, the purpose of multiple seat decks is to bring the greatest number of spectators as close to the center of action as possible while providing optimum viewing.

Unfortunately, as the number and size of decks increase, so does the ratio of ramps, concourses, concessions and toilet facilities needed to support them. These items, in conjunction with increased structural demands, increase the cost per seat dramatically.

Increasing the steepness of seat decks is another method of bringing spectators closer to the action, but spectator comfort limits the acceptable inclination to 38 degrees or less.

Movable Stands Offer Flexibility

Perhaps the finest example of how technology can lend itself to the increasing flexibility of seat decks is the development of movable stands.

Because of the different configurations of the playing fields for football and baseball, it is difficult to achieve a good seating arrangement for both sports. Robert F. Kennedy Stadium in Washington was the first to employ the principle of moveable stands.

Here, a block of about 6,000 seats are moved on a system of two tracks, one on the stadium wall, and one beneath the surface of the field. This group of seats can be rotated by tractor power as a unit from the third-base side for baseball to the sideline for football.

Since then, other stadiums such as Shea Stadium in New York, Busch Stadium in St. Louis and Three Rivers Stadium in Pittsburgh, have incorporated moveable stands.

Domes Provide Comfort—At a Price

The current trend toward domed stadia has created a seat deck with a totally controlled environment. To achieve this, a column-free interior space of 600 to 800 feet in diameter is required.

Air-supported domes, generally utilizing a high-tensile-strength, Teflon-coated fiberglass fabric, have spanned these vast interior spaces with relative economy.

Rigid dome structures, on the other hand, tend to cost more. The 65,000-capacity Seattle Kingdome, with its reinforced concrete roof structure, was built at a cost of approximately $2,120 per seat.

The granddaddy of them all, of course, is the New Orleans Superdome. This 80,400-capacity structure, with its lavish appointments, cost approximately $4,820 per seat.

Quite the bargain by today’s standards were the designs of Tiger Stadium (Brigg’s Stadium) and Cleveland Municipal Stadium. These costed $23.80 per seat in 1912 and $36.40 per seat in 1930, respectively.

Seats Can Be Plush or Plebian

Today’s stadium seats range from spectators sitting directly on precast or concrete tread and risers to the deluxe press box “V.I.P.” swivel chair, replete with fine upholstering, contoured backs and arm rests.

For those who must upgrade old wooden plank seats, molded fiberglass covers at $4.50 per seat many be a simple expedient. Be careful though: some types will deteriorate with age and may need to be replaced.

Going to the next step up we have the riser- or tread-mounted plank seat, most often made of anodized aluminum extrusions mounted on aluminum angle brackets, for about $10 to $12 per seat. Aluminum, unfortunately, is hard to sit on, feels hot or cold and has hard corners. The movement at butt joints can be uncomfortable or painful.

As a modification to the plank seat, we have the added option of installing a contoured back. This increases the cost of the basic plank seat by about $15 per seat. Often an old stadium may be upgraded from plank seats to deluxe seats with backrests, but first be careful to verify proper seat clearances required by code.

The top-of-the-line fold-down chair seat is the utmost in comfort for today’s outdoor seating needs. This comes, of course, at a price. At $45 to $55 per seat, they are not only significantly more expensive than any other form of seating, but they also require approximately 32 percent more room than plank seats.

A Delicate Balancing Act

It’s apparent that stadium seat designers face a multitude of often-conflicting parameters that require skill and ingenuity to create a successful design. In the future, the spectator will change very little, but his list of needs and desires will, and so, appropriately, will the designer’s choice of trade-offs and compromises.

About the Author

Dale L. Swearingen, AIA, is vice president and director of architecture for Osborn Architects-Engineers of Cleveland, Ohio. Involved with sports facilities since its design of Fenway Park in Boston, Detroit’s Tiger Stadium, Yankee Stadium in New York and Cleveland Municipal Stadium, Osborn’s more recent projects include seating expansions at Milwaukee County Stadium and Tiger Stadium at Louisiana State University, RFK Stadium in Washington, Three Rivers Stadium in Pittsburgh and Miami (Ohio) University’s Fred C. Yager Stadium.