The push toward participation growth is leading women into pools and multipurpose rooms, onto the gridiron and even to the local bowling alley

Credit for expanding opportunities for women athletes is usually given to Title IX of the Education Amendments of 1972, the groundbreaking law that prohibited sex discrimination in federally funded educational settings. But it would be more accurate, really, to say that it has been the women themselves, whether in youth, high school or collegiate sports settings, who have taken the ball and run with it.

In the years following the passage of Title IX, high school girls took to sports such as basketball, volleyball, field hockey, tennis, track, swimming, soccer and softball in unprecedented numbers. At the college level, the Association for Intercollegiate Athletics for Women (AIAW), founded in 1971, shepherded the creation of women's sports programs - comprising those offerings, plus many other Olympic sports - at hundreds of institutions. But while females flocked to sports programs throughout the 1970s and '80s, there gradually became an acknowledgement that the programs being offered girls and women weren't sufficient to meet either the full slate of their interests or the prong of Title IX dealing with "substantial proportionality" (the linking of the athletic participation rate to each school's overall enrollment ratio of males to females). Thus, the concept of "emerging sports for women" was born.

Additions to the typical high school program have mostly remained piecemeal, with communities, states and regions starting up sports teams or sanctioning championships for less popular activities when asked (or, often, pressured) by parents and students. Meanwhile, the emerging-sports concept gained traction in the realm of higher education after the National Collegiate Athletic Association's Gender-Equity Task Force codified it in 1993, identifying nine sports (see list, p. 56) for which the association would accept a lower initial standard for sanctioning a national championship (40 varsity teams, as opposed to 50 for men).

"Piecemeal" could describe the emerging sports selection process, as well (a primary criterion used to draw up the first list appeared to be whether a sport could claim strong conference support). But there can be no doubt that the process has had several spectacular successes. Participation in women's rowing has simply exploded, continuing its rapid rise after gaining championship status in 1996 to 141 teams and 6,690 athletes in 2002-03. Ice hockey participation has surged to 70 teams, mainly in the Northeast and upper Midwest, and also helped boost participation at the high school level. Two other sports on the original list, water polo (56 teams) and bowling (43 teams), have officially shed their emerging-sports status.

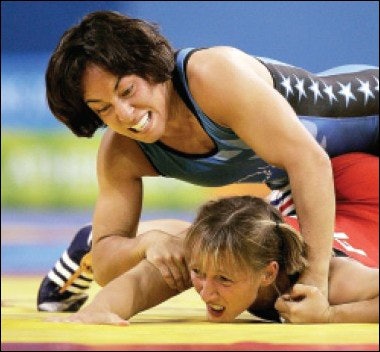

The idea of emerging sports for women, while almost universally applauded, has attracted its share of criticism. Proponents of some Olympic sports say the more-recent criteria implemented by the NCAA (see box, left) makes getting on the list too difficult; others say sports should remain on the list even after crossing the 40-team threshold, in order to sidestep the possibility that the sports' gains will either plateau or erode. Yet others contend that more-traditional and egalitarian sports already owning championship status - such as lacrosse and field hockey - could benefit greatly from the extra attention now given highly specialized sports such as equestrian and synchronized swimming. Another school of thought holds that the NCAA's efforts, though welcome, are largely beside the point; witness the emergence of women's professional football and the success enjoyed by the United States women's wrestling team in the 2004 Olympics - two sports that are clearly moving forward without the NCAA's imprimatur.

With all of this occurring against a backdrop of budget cuts at the high school level and runaway athletic department deficits at the collegiate level, it may well be that the effort to identify and support new programs for women is about to enter a new phase. For all the sports referenced on the following pages - whether they are still fighting for administrators' and athletes' attention, or even if they've already "emerged" - the future remains uncertain.

Finding a Niche

If you're an aspiring equestrienne, it helps to be from Michigan. Of the 80 high schools nationally sponsoring equestrian teams, 75 are located in the Wolverine State. Want to play water polo. Better move to California, where 446 of the 629 high school teams (and 12,185 of 16,392 athletes) reside.

That's the scattershot nature of emerging sports in secondary schools. The distribution roughly mirrors collegiate emerging-sports development, with ice hockey played in the northern tier, lacrosse in the mid-Atlantic states and so on, but high schools are less orderly and thus capable of surprises. Girls' weightlifting, which 10 years ago was centered in the country's midsection (Michigan, Ohio and Kansas), has found a home in Florida, where 64 percent of 214 school teams are now located. Girls' wrestling has been sanctioned as a championship sport only in Hawaii and Texas, with California (and recently, Florida) a growing presence on the scene. Water polo teams play in large numbers in three seaside states (California, Florida and Hawaii), and one landlocked one (Illinois). Public high school equestrian programs in horse country, such as Kentucky, Virginia or Maryland. Zero.

In some of these cases, the reasons for not adding a new sport are often based on financial concerns or other local circumstances. In the case of equestrian, both apply: The costs to run such programs are high and, in any case, private boarding equestrian schools exist to serve this group of athletes. But data collected two years ago by the Women's Sports Foundation (WSF), pairing the most recent enrollment and participation data then available, suggests that, in general, the states closest to reaching substantial proportionality tend to be in the northern tier and feature smaller populations and higher per capita incomes. Those at the bottom of the list tend to be a) states that are rural and in the South and Mountain West, b) states with lower per capita incomes, and c) states whose athletic departments are more football-oriented. "It's almost a measure of liberalness," suggests Donna Lopiano, the foundation's executive director.

The data is more than just interesting - it could potentially be predictive, auguring the states with the biggest potential for emerging-sports growth. At the high school level, that probably means weightlifting, wrestling, martial arts, water polo and bowling. All of these could utilize existing facilities and be started up at relatively low cost, with little burden on athletic contest scheduling. Adding water polo and bowling would, since they've moved up in NCAA status, offer the extra benefit of potential college scholarships for female athletes.

Mississippi (number 49 of 51 on the WSF proportionality list) apparently recognized the benefits of girls' bowling when it recently became the 15th state to add it as a varsity program. Mississippi's decision is particularly interesting in that bowling has in its history been mainly an urban phenomenon (states serving the largest numbers of girls' high school bowlers are Illinois, New York and New Jersey). Just don't tell Kevin Gabinski, an account executive with High School Bowling USA and College Bowling USA (two organizations under the umbrella of the American Bowling Congress), that the sport's popularity is "trickling down" to states like Mississippi from the college level. "It's trickling up," Gabinski says, noting that the more than 16,000 girls' high school bowlers collectively dwarf their 370 college counterparts. "Or at least, it's going back and forth. As more colleges add it, there's more demand at the high school level. Then when more states sanction it, there's more demand at the college level."

But getting high schools to add programs takes a long time, Gabinski says, and it takes the dedication of a lot of special interests, from the athletes themselves to groups like his - and in the case of bowling, to private bowling proprietors.

"Youth bowling became a priority within the bowling industry as ABC membership kept declining," Gabinski says. "Studies kept showing that the drop-off was when kids got to high school, and we weren't getting those people back until they were 25, 27 years old, if we got them back at all. Now we have 15 states offering varsity bowling and another 20 states operating high school teams at the club level, with a lot of the state championships run by local bowling proprietors who want to see high school bowling grow."

Mike Lewis, director of sport development for USA Water Polo, can only dream of such a situation. In spite of being "the most cost effective of all intercollegiate sports" (as the NCAA described it in its emerging sports manual), collegiate women's water polo participation has leveled off since the sport achieved championship status. And while Florida recently became the third state (after California and Illinois) to make it a championship high school sport, participation rose just 41 percent in the past five years after jumping 423 percent in the previous five.

"I guess I'm a realist," Lewis says. "I wouldn't say we're dissatisfied; we're making progress. The NCAA just expanded the women's championship bracket from four to eight teams, and we're starting to see it grow outside of California, which is really promising. In the high schools, we're hoping Texas will be our fourth varsity state. Our women won the Bronze medal in Athens, which certainly helps. So we're hoping to see continued growth, and continuing to lobby for the sport. We're keeping our ear to the ground."

Emerging Controversy

National governing bodies (NGBs) and others who have a vested interest in the matter would like their sport to be the college ranks' next women's rowing. Starting with 51 teams and 1,555 athletes the year the Gender-Equity Task Force drafted its initial report, rowing jumped to 98 teams and 4,443 athletes (and championship status) in just four years. Bowling, though counted as another emerging-sports success story, took far longer: Eight years of almost no growth, followed by a two-year spurt to championship status.

From the standpoint of athleticism, the two sports have little in common. Rowing is a sport requiring strength and endurance; bowlers require precision and accuracy (though they must also endure endless jokes about their sport). A better comparison to bowling, skillwise, is golf: Like bowlers, golfers spend hour after hour, month after month, practicing the same repetitive motions, getting their "stroke" down. Bill Straub, longtime head coach of the University of Nebraska's club bowling program (and, since it went varsity seven years ago, head coach of the reigning national champion women's team), describes it this way: "To me, the differences are image-related, from the advertisers on down. Smith Barney sponsors golf, Wal-Mart sponsors bowling. The golfer drinks champagne, the bowler drinks beer. But there's also a different mind-set in the way the two sports do business: If you go to the same golf course three times and are still in triple figures, there'll be someone looking over your shoulder wanting to know if he or she can help you lower your score. A bowling center wants to make sure you're well fed and not thirsty."

What bowling and rowing do have in common is that both have become magnets for Title IX-related criticism. Rowing rosters have proven extremely flexible, with the average women's collegiate rowing team accommodating 47.4 athletes today, up from 30 women per team in 1992-93. Because of this, much of the sport's growth is attributable to athletic directors' use of it as a way to offset football's huge rosters; some women's crew squads have begun their season with as many as 170 students (see "Open Oar Policy," Nov. 2002, p. 32). Women's bowling, while it can offer just five equivalency scholarships to the typical squad of 12 players (as compared to 20 scholarships for crew), is nonetheless perceived as rowing's twin sister: An activity populated not by athletes committed to sport but by students looking for a free ride to college.

"Crew is one we have issues with, because they're pulling women off campus who've never done crew before, and they're giving them scholarships," says Gary Abbott, director of communications for USA Wrestling, which has been at the center of a long-running legal battle with the NCAA over what the group says is Title IX-mandated cuts of men's teams. "They're doing it just for the proportionality aspect, filling spots."

Lopiano has heard about as much of these arguments - and their corollary, that women's teams have to scrape to fill their rosters - as one person can stand. "You hear people complain, 'Look at these women, they have to post signs in the locker room begging women to come out for crew: Scholarships Available,' " she says. "Those signs have been posted for men's crew forever. They've been trying to recruit the biggest, burliest football players from day one. Recruiting from a college student population is not a sign of lack of interest, it's a sign of wanting to get the biggest kids. You see it at the high school level, too. The football coach looks around at the incoming class and says, 'You're big, come over here, you're coming out for football.' Why is it right for men, but implies lack of interest among women?"

Surprisingly, Straub is not entirely unsympathetic on the scholarships issue. "A school on the East Coast that recently added women's bowling placed an ad in The Wall Street Journal and New York Times looking for girls with a pretty low average, saying that if they'd commit to play there they'd get a full ride," he recalls. "Is their objective to succeed, or to fill a political need. An awful lot of the schools that have adopted bowling have done so for political advantages, not for competitive reasons, and you can tell by how their programs are run."

Straub notes that, in some of these cases, schools are creating bowling programs from scratch, meaning that it will take time for the quality of varsity bowling to spread downward from the top tier. It also suggests, for him, an even more troubling reality. "Some have given the keys to the program to someone within the department who was an assistant coach of one of their other sports rather than get someone from outside," he says, "because it's the same old perception, 'Oh, it's only bowling. Pick up a ball, throw it down there, if they don't all fall, you pick up the ball and throw it again.' Well, they're finding out now that the technical skills necessary to really succeed are no different than they are in any other sport where you throw or hit a ball."

Bowling at least has the advantage of 180 women's club teams on college campuses - "And we're trying to get everybody to go varsity," says Keanah Smith, the NCAA's assistant director of championships for women's bowling and lacrosse. It also has a long tradition at historically black colleges, which count for 21 of the 26 Division I women's bowling teams. ("They had everything in place, says Lopiano. "All they had to do was call it varsity.")

Women's wrestling, on the other hand, has little in the way of a high school feeder system - primarily girls wrestling on boys' teams - and no history as a collegiate women's sport. In fact, of the four current or former college wrestlers representing Team USA at the sport's Olympic medal debut in Athens earlier this year, two wrestled on men's college teams and all four wrestled on boys' high school teams. "Girls want to wrestle," Abbott says. "You see how many are wrestling boys." (Abbott's reference is to the 4,008 girls who wrestled in high school in 2003-04; the NCAA, which keeps track of the 29 badminton players and 43 archers competing in college, doesn't keep figures for women's wrestling. "Until you get emerging sport status, the NCAA doesn't recognize that you exist," he says.)

Worse still, women's wrestling has yet to get anywhere close to the first of the NCAA's criteria for making the list of emerging sports: Twenty or more varsity teams and/or competitive club teams. The sport boasts (if that is the word) six varsity programs, four of which are in the NAIA and one of which is at a junior college, plus about the same number of club teams. Abbott concedes that his organization must do more to promote the sport, and is pinning his hopes on schools with existing men's programs - "If colleges have men's wrestling, it's not much of a reach to add a women's program" - and an Olympic honeymoon. "Obviously, we have to work harder to get the colleges excited about it," he says. "If they were paying attention to the Olympics, they should be excited about women's wrestling. But really, it's up to athletic directors to decide to give our sport a chance."

In the Trenches

Athena Yiamouyiannis, now the executive director of the National Association for Girls and Women in Sport, was at one time director of membership services at the NCAA and staff liaison to its Committee on Women's Athletics. As someone on the front lines as the concept of emerging sports itself emerged as an NCAA priority, Yiamouyiannis saw some of the drawbacks of writing criteria for sports to make the emerging sports list - or of keeping a list at all. For one thing, there was the issue of whether sports should be removed if they don't show measurable progress. "The committee eventually said, 'We're not going to keep the sports on the list indefinitely. They either will rise to championship status or they'll be taken off," she says, though this falls short of explaining why archery and badminton remain there. Another concern, as mentioned previously, involved sports that could use a boost but already had championship status. However, she says, "It was just intended to help introduce sports that other people might not have thought of. It was never meant to help promote everything - and we do look at it as having been successful."

The area in which colleges and universities have been least successful is certainly women's contact sports, in spite of the persistence of rugby (two teams) on the list. (While women's ice hockey has made big gains at the high school and college levels, the sport outlaws body checking.) Contact sports with upside potential include rugby (a growing collegiate club sport), wrestling (the latest Olympic sport), martial arts (a mainstay at private studios and health clubs) and football (now grabbing market share as a minor professional sport).

Yiamouyiannis says the biggest problems facing rugby and football are the high costs for starting these programs and the sheer number of athletes needed to field teams. To this Lopiano adds (with a laugh) the probably insurmountable problem of sharing fields with men. But, she says, "I suggested football to the NCAA Committee on Women's Athletics probably eight years ago. I feel that if the NCAA took the initiative to create football rules in the same way that the women's game is different in ice hockey - a more commonsense game than these hulking bulks killing each other, more like Australian Rules Football - that it could be tremendous. Look at the number of women who are participating in recreational flag football at the college level - they love it to death. They'd play in a second."

Dawn Berndt, executive director of the Women's Professional Football League (and also player-owner of the league's Dallas Diamonds), says the field issue is all too real, and part of the reason for the sport's lack of a female-based feeder system. "It's hard enough to get schools to allow us to play on their fields, much less to get them to think about letting girls play," she says. "In Texas, where I am, it's not as hard because a lot of the fields are synthetic turf, but in most other areas, we fight every year to get fields to play on."

As for changing the rules, though, Berndt says no thanks.

"Women who want to play football want to play the real thing," she says, noting that her league's few alterations from NFL play consist of the use of a smaller ball and a 1-inch kicking block on extra points and field goals, kickoffs from the 45-yard line, and a ban on blocking below the waist. "We find that the women who play flag football don't want to play tackle. They're in it for the fast pace of flag, not for the down-in-the-trenches hitting of football."

Consequently, the WPFL attracts (in addition to speed burners from track) a number of players who banged in the paint in basketball, blocked spikes in volleyball, piled into the ruck in rugby and took out the pivot man on double play balls in softball. It also has quite a few players (as with rowing) who never played sports prior to coming out for football. One of those, Cabrina Gilbert, started playing pickup beach tackle football in her native Southern California when she was in her mid-twenties, graduating to flag football as recreational leagues there became more prevalent. When she moved to Syracuse, N.Y., Gilbert figured her football days were over - but then she went to a tryout for Syracuse's startup WPFL franchise. "Now, I'm a 'big grrl,' as we call ourselves in the biz, and I figured I couldn't make a professional team," she says. "But I did. It turns out I was the only one who had ever played football." Gilbert is now owner of the WPFL's Syracuse Sting.

One group that is conspicuously underrepresented in the WPFL is women who once played football on boys' teams in high school (that figure nationally reached an all-time high of 1,527 last year). Gilbert, who has one such player on the Sting (April "Watchdawg" Clarcq), estimates that at most, 2 percent of the league's athletes played in high school.

"I'm sure that number will grow," Gilbert says. "More girls write to us each year saying that they are playing in high school. Most are on the edge of giving it up or have already, because the boys aren't very nice to them."

"We try to support girls playing on boys' teams in whatever way we can," Berndt adds. "It's hard for them. We'll send players out to watch a girl's games if she's within, say, an hour's drive. I hope more girls play in high school and college, because it'll help us grow."

Observers of the struggle for gender equity say they've seen the future, and it's cheerleading. (See "Leading the Crowd?," Jan., p. 24.) Says Lopiano, "I know there is a move afoot for an NGB to be established that would take cheerleading down the proper road to a synchronized, tumbling version of the sport. That would be fine."

If cheerleading is to establish itself first as an emerging sport and then a championship sport, its proponents will be fortunate to have several successful sports to emulate. Straub recalls that he applied pressure to the Nebraska athletic department, but says that then-AD Bill Byrne, now AD at Texas A&M, deserves all the credit for making bowling a varsity sport. "I included in my pitch that not only could it have a gender-equity benefit, but it was also an opportunity to garner more points toward what was then called the Sears Trophy," Straub says. "I knew, and Bill recognized, that we had a program on campus that wouldn't embarrass the department and that had a chance to make it more successful."

Lopiano says this is why athletic conferences, whether collegiate or high school, play such a vital role in helping sports emerge. "It takes some champions for the sport, and it takes some conspiracy in a very positive sense," she says. "Schools have to say, 'OK, we haven't done a great job of finding opportunities for women, let's get all the schools in our conference together, decide what's best for all of us, and add a sport. Where can we do the best job? Where can we win championships?' As soon as you figure out a win-win, it can happen."